Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity, awe and wonder.

And somehow, that was almost a year. Eleven months (and 8,000 more of you reading than when season 5 began). Good grief, to all of it.

The extended nature of this season was very much not according to the original plan: previous seasons have been 2-3 months long, and I thought this one would pan out the same way. But life intervened, mostly in good ways - including how I’ve now upgraded my headquarters from a tiny wooden cabin into a proper little flat! (A move of just a few miles into a nearby town, so I can continue to enjoy the natural delights of western Scotland around me. You’d have to drag me away at this point.)

So, yes, here we are. And since things have calmed down again, season 6 will be a much brisker and punchier affair when it arrives in a month or so. More on that in the next newsletter.

But today, here’s what we’ve covered over the last 45-ish weeks in 37 different newsletters - and since that is an unusually enormous amount of stuff for a single season of this thing, two things are different about this roundup:

it’s the first of a two-parter, with the second half coming over next time, and…

it’s definitely going to be too big for your email Inbox.

If you’re reading this in your email, somewhere down below, you’ll see it’s clipped off in its prime by your email provider - which means you’ll have to click through to the Web version to read the whole roundup.

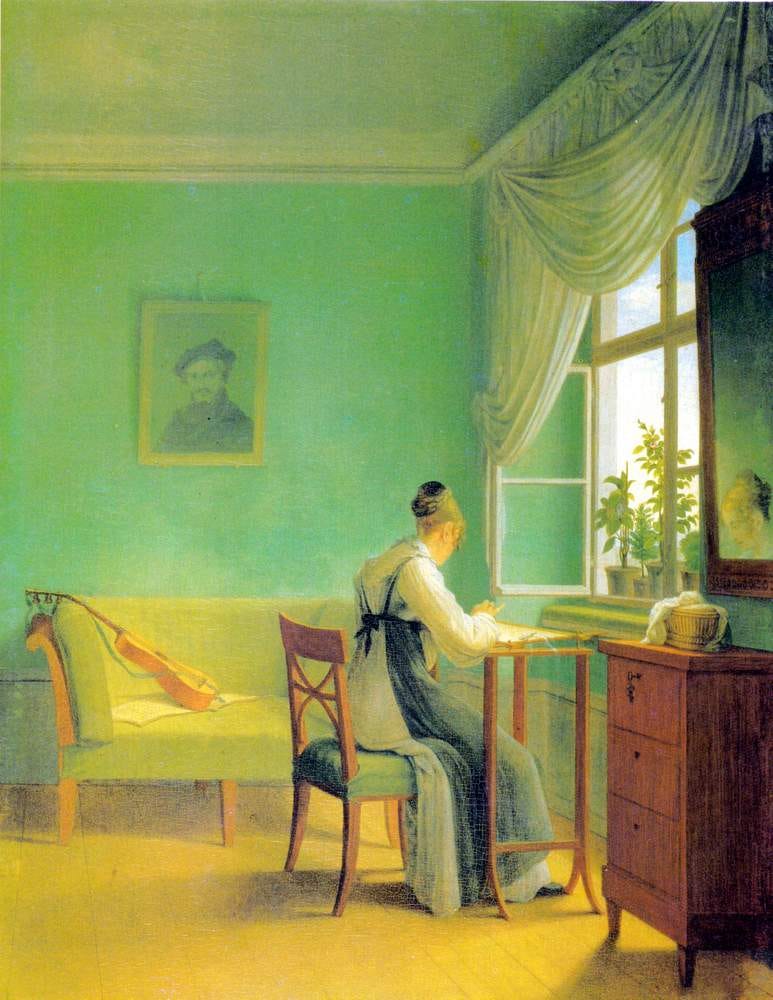

(To do that, just click on the title of this newsletter - “Season 5 Is Done! What's Next? [Part One]” - and that Web version should open up in your browser.)

Also, since the main topic this season is the frequently bizarre world of colour, you may want a primer on some basic optical principles - so here’s

‘s Phil Plait laying them out for you from an astronomer’s perspective:(That whole multi-video course is about astronomy, and it’s really great - and totally free! Watch them in order by starting here.)

OK - here’s what Everything Is Amazing has looked at this year:

Main theme: Colours (for free and paid subscribers)

1. A Hundred Million Ways To See

“ “I always felt like I was living in a very magical world. I know children say that, but for me, it was like everything was hyper-wonderful, hyper-different. I was always exploring into nature, delving and trying to see the intricacies, because I’d see so much more detail in everything. Someone else might look at a leaf or a petal on a flower, but for me, it was like a compulsion to really understand it, really see it, and sometimes spend a lot of time on it. And I just wanted to paint and portray everything that I was seeing.” - artist Concetta Antico, quoted in The Guardian

Through the eyes of non-artists like me - OK, that’s a lovely way of putting it, but come on, get scientific please. Isn’t this just a fancy way of saying “I have a really great creative imagination”? No disrespect, but isn’t rhetoric like this just stringing beautiful words around something too mysterious to define, and - um, well - effing the ineffable?

One of Antico’s students, a neurologist, didn’t think so. They emailed Antico a science paper about a rare eye condition related to the colour-blindness that Antico’s daughter had recently been diagnosed with. Intrigued, the artist contacted the team of scientists that wrote the paper - and shortly after, Antico took a saliva test that confirmed she had a rare genetic mutation in her eyes.”

2. Why Classical Greece Looked Like Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory

“If you walked through the Parthenon in Athens, it would have been, in the words of historian Natalie Haynes, “a riot of colour and glitzy decoration”. Wherever a statue depicted metal, that would be painted gold, or silver, you know, in the really shiny way. Newly cast bronze would have been treated to have the faint look of - how can I say this - brown moulded plastic.

Everything would have looked, by modern standards, appallingly cheap. Most of us used to the monochromatic grandeur of Westminster Abbey or the White House would be appalled. Horrified. It would look like the most wretched of parodies, utterly lacking in good taste.

What were they thinking?”

3. The Blue Of Distance, Hope - and Mars?

“Scattering explains why our sunsets are red: at that angle, the light has passed through so much atmosphere that all the blue has been scattered out, leaving wavelengths towards the red end of the spectrum.

But on Mars the rules are different. The weak Martian air (95% carbon dioxide, 2.8% molecular nitrogen, a wee pinch of argon) contains a lot of dust particles which are a lot closer in size to the wavelengths of visible light. This leads to a different form of scattering, called Mie, where longer wavelengths (redder ones) tend to scatter equally in all directions, while shorter wavelengths (the blues) scatter at slighter angles. (This effect also happens here on Earth, but it’s swamped by the far more common Rayleigh scattering).

The result is that on Mars, the daytime sky is flooded with ‘lost’ red light. But - what about sunsets? Would the reverse be true?

Ohhhhh yes indeed it would.”

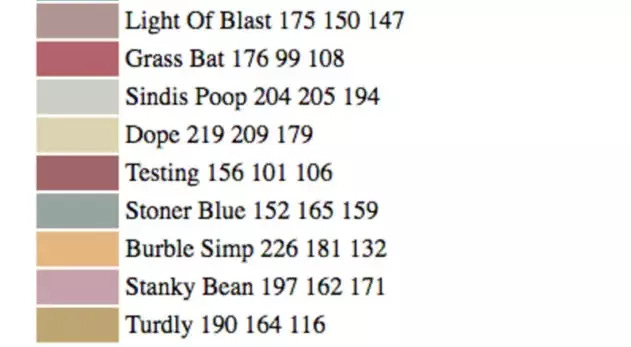

4. How To Invent Your Own Colour

“It’s 2017, and optics research scientist Janelle Shane finds herself at a loose end. What would be both a credible piece of research and a hilariously dumb use of her programming skills?

Ah! Of course. How about teaching her neural network to act like an Elizabethan dressmaker, by inventing a bunch of new colours from scratch?

“For this experiment, I gave the neural network a list of about 7,700 Sherwin-Williams paint colors along with their RGB values. (RGB = red, green, and blue color values.) Could the neural network learn to invent new paint colors and give them attractive names?"

The answer was a fairly emphatic “No”. ”

5. Why Pink Has Absolutely *Everything* To Say

“Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764), a mistress of France’s Louis XV, is widely credited for sending the popularity of pink through the roof. (One echo of this: the influential Sèvres porcelain company created and named a new shade of pink after her.)

At this time, pink didn’t mean “men” or “women” - it meant wealth, status, giddily high fashion and smouldering desirability. And not just in France, of course: across Europe, the influence of French fashion was impossible to ignore, leading to foppish copycats and nationalist backlashes galore - because, you know, people.

However, some time in the 19th Century, things started to shift. For some reason (perhaps the availability of cheap new dyes), men across Europe started going for darker shades.

Nevertheless, as Kassia St Clair notes in her endlessly fascinating essay collection The Secret Life Of Colours, an 1893 article in the New York Times on baby clothing recommends assigning “pink to a boy, and blue to a girl.” A trade publication published 25 years later helpfully elaborates that pink is “the more decided and strong colour,” while blue is “more delicate and dainty.” ”

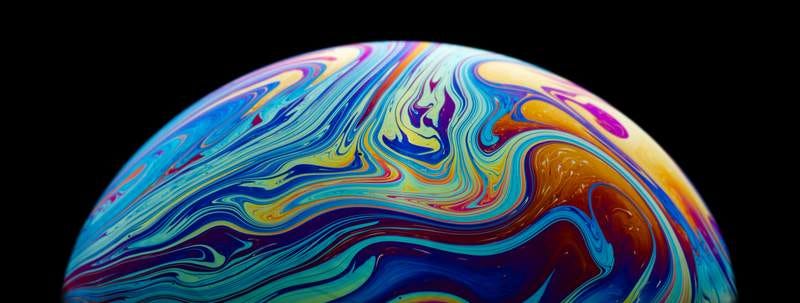

6. How To See Impossible Colours

“The way it works is simple, and you can do it three times, one for each row (giving your eyes a bit of a break in between doing each one).

First, you stare intently at the cross in the centre of the coloured circle in the column named “fatigue template” - then after maybe 30 seconds, or after as long as you can hold it, you dart your eyes sideways and stare at the cross in the “target field” box.

Okay! All done? How did you get on? And did you notice anything really weird about those colours?”

7. What If We Could Change The Colour Of *Everything*?

“[A]s everyone knows, the chameleon has the ability to change colours to blend into its background, to hide from predators.

Except, well - everyone’s wrong. From recent research, it seems this isn’t what chameleons are doing. They’re changing colour either to regulate their temperature - because chameleons can’t generate their own body heat, so they turn darker when they’re cold to absorb more heat, or vice versa - or they’re doing it to communicate, mainly to each other.

Just ask anyone who has a chameleon as a pet, and they’ll tell you they can read the chameleon’s emotional state from the pattern of colours it’s wearing that day - and they’d probably be right.”

8. The Green That Poisoned Britain

“It’s 1861, and 19-year-old Matilda Scheueur isn’t feeling well. Not well at all.

She’s working as a florist, and it’s part of her job to go round all the artificial flower headdresses and “fluff them up,” dusting them with powdered Emerald Green paint to brighten up the colour.

(Emerald Green is now the nationally preferred, near-identical alternative to Scheele’s Green, thus continuing the ill-starred scientist’s lifelong curse of never getting lasting credit. Although, considering what happens next, that could be a blessing…)

Now Matilda is getting sicker and sicker. She’s suffering convulsions. She’s vomiting green water from her mouth and nose - and it’s even coming out the corner of her eyes, the whites of which now have a distinctly green tint, as do her fingernails. She’s telling people that everything is starting to look green…

How can this be happening with a safe, everyday green paint that everyone has been using for decades?”

9. Oh, How Our Cities Will Shimmer

“I’ll tell you one thing from experience: walk down a white-painted street in the Greek islands on a blazingly hot day, and your eyes are going to get a battering.

All that reflected light still has to go somewhere, and where it goes is into your face. Simply bouncing the sunlight off would condemn future inhabitants of our cities to the urban equivalent of snow blindness, unless everyone wears the kinds of cool sunglasses that science fiction’s been telling us everyone in the future should be wearing. Nevertheless: doesn’t feel like a complete solution.

So how about less reflective colours that deliberately absorb heat - then process it into an energy source? This seems a very fruitful avenue of research, and I’m sure solar panels are the uppermost tip of the iceberg here.

But it could be that the most useful colour for buildings of the future is - well, all of them, all at the same time.”

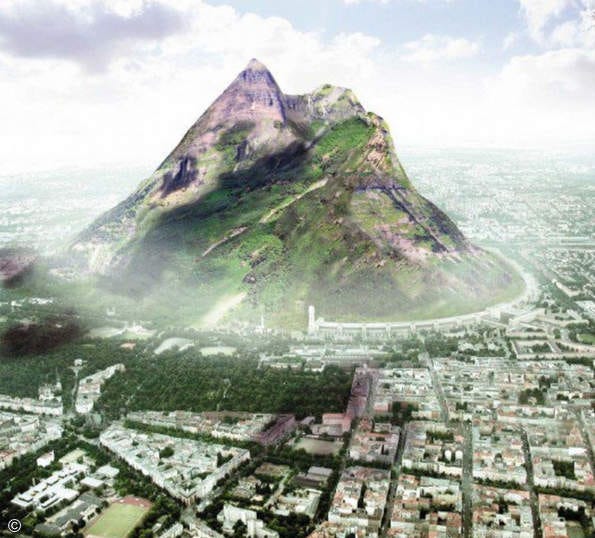

Sub-theme: How Geology Affects Modern Life (for paid subscribers, with a few posts unlocked for everyone)

“Human beings have understood the relationship between mountains and rain since…well, probably since they became human beings. And it’s been just over a century since the formal study of the atmospheric sciences (mainly for weather prediction) took off in academic settings…

And now, it seems some people are starting to regard mountains as tools. The kind we can build ourselves, to get the results we want.

Okay! Uh. (Yikes?)”

11. To Make A Mountain -1: Why Nobody Has The Time (Paid Subscribers Only)

“It’s one thing to have an inkling that the continents have somewhat moved around since ancient times…

(Most people have heard of Pangea, the super-continent that formed around 300 million years ago, when the first-drafts of our modern continents were smooshed together into one big lump. As a schoolkid, I was transfixed by the way you could see how the edges of modern continents sorta-kinda fit each other like a planet-sized jigsaw puzzle.)

…but it’s another thing to see the world flowing in all directions like the contents of an egg cracked into a frying pan, to watch it all float around seemingly chaotically.

If you think of the crust (ie. all the “land” on Earth) as the foam sitting atop a fresh cappuccino, then every few hundred million years, the whole thing gets a proper stir with a metaphorical spoon. Nothing stays where it is. Everything gets moved along.”

12. To Make A Mountain - 2: The Science Of Feeling It (Paid Subscribers Only)

“As the Second World War draws to a close, a Scottish writer sends her latest manuscript to her friend, the novelist Neil Gunn. What does he think?

She’s struggled with her writing for a while, worrying that her poetry about the landscapes around her is too much a reflection of them - beautiful but ice-cold, compelling but in a glittery, mineral way. In 1931, in the wake of a six-year run during which she produced three well-received novels and one book of poetry, silence struck her with devastating force. She wrote to Gunn:

“I’ve gone dumb…one reaches (or I do) these dumb places in life. I supposed there’s nothing for it but to go on living. Speech may come. And if it doesn’t I suppose one just has to be content with being dumb. At least not shout for the mere sake of making a noise.”

It’s been a long, hard road to find her voice again. This new draft, only 30,000 words long, is the only major piece of writing she’s produced in this decade after her voice faltered.

But this book isn’t like anything she’s written before - or like anyone else has, perhaps.

13. Walking The Great Mountain Trail Of Deep Time (Paid Subscribers Only)

“As I wrote about previously, the longest mountain range on Earth is 65,000 km long (40,000 miles), which sounds like a proper adventure until you discover it’s thousands of metres deep at a depth that’d be instantly, messily fatal to an unprotected human being. Not anyone’s idea of a fun day out.

But now I’ve discovered the second-longest, and it’s far more manageable. Nope, it’s not the Himalayas (they’re piddling in comparison). It’s also not the Andes (the third-longest).

This thing is bigger - and, incredibly, it’s on land. You could, in theory, walk along it.

14. Did This Tree Of Fire Break Our World Apart? (Paid Subscribers Only)

“Our world plunges to a mighty depth - and to date, humanity’s only drilled through around 12km of it. That’s over a quarter of the way through the crust, which seems (and is!) a lot - but that’s also a bit less than 0.2% of the whole way down. Under one-five-hundredth. Good grief.

It’s not surprising that this is such a lively field of startling breakthroughs and continent-sized question marks. There is still so much that’s unclear and so much being discovered every year…

And nothing illustrates this better than the science of mantle plumes.”

15. Beware The Thousand Invisible Hands

“Corryvreckan is so frightening not just because the current might pull you under, but because it might hold you under.

For the Channel 4 programme “Equinox: Lethal Seas” (2000), a documentary team from Scottish independent producers Northlight Productions threw a realistically weighted mannequin into the water near the Hag during the flood tide, wearing a life jacket with a depth gauge.

When they recovered it half an hour later, the depth gauge had stopped taking readings beyond 200 metres - with evidence of being dragged along the bottom for a great distance, presumably after the downward current worked like a waterfall to hurl it all the way down to the sea floor before pulling it onwards.”

16. Plastic Rocks & Technofossils: Why New Geology Is Getting Weird (Paid Subscribers Only)

“A recent survey of existing minerals by the Carnegie Institution for Science in the US found that 4% of them - 208, to be exact - showed signs of originating from human activity.

(There are many ways this can happen, from minerals decomposing and leaching into each other as electronic waste rots - or fails to rot - in dumps, from mine shafts exposing subterranean minerals to new humidities and temperatures for the first time, to unnatural deposition patterns dumping things on top of each other in quantities that could never occur naturally. It’s a whole mess of stuff, for the widest, occasionally strangest of reasons - like our ongoing obsession with gold, one of the most chemically uninteresting elements on our planet, which we’ve decided is worth more than almost everything else because - sigh - it’s delightfully shiny.)

Then there are the rocks that geologist Fernanda Avelar Santos found on Trindade Island off the coast of Brazil in 2019. Their striking colour caught her eye - a blue rock base, streaked with threads of a livid bubblegum-green colour. What exciting new mineral could this be?

Alas, not a mineral. The culprit was a local spill of plastic pollution - and a new geological process, where plastic was binding with rock and sand and other detritus to form a new substance nicknamed plastiglomerate.”

17. Why It’s Great News That The Earth Sucks (Paid Subscribers Only)

“Pratt does the calculations - and they’re still wrong. Except now they’re wrong the other way. The discrepancy due to the gravitational attraction of the Himalayan mountain range is smaller than it should have been. They’re exerting less pull on the plumb bob than expected…

It’s almost as if the mountains are hollow.”

Everything Else (for a mix of paid subscribers and everyone)

18. Why We Need More Goats On The Moon (Paid Subscribers Only)

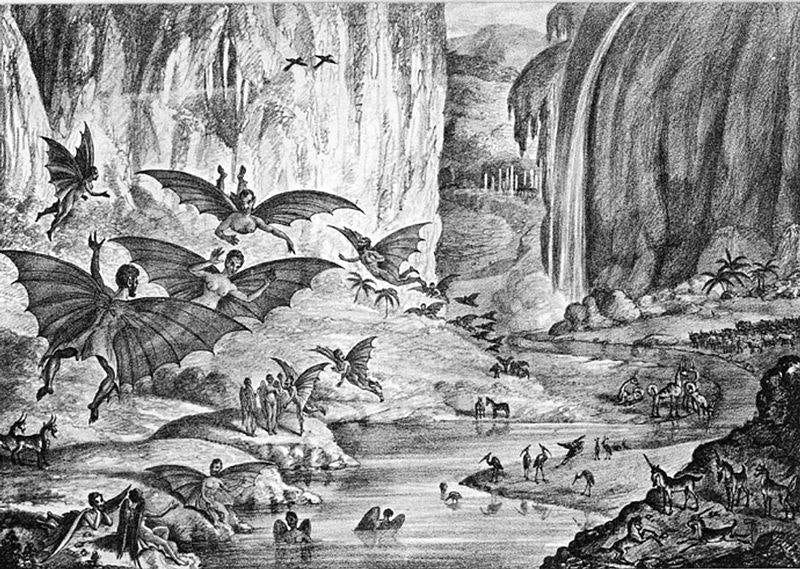

“The first article continued: not only had Herschel used it to discover new planets outside our Solar System, he had also “solved or corrected nearly every leading problem of mathematical astronomy.” (How exciting! Whatever those problems were, it was so reassuring to know they were now solved.)

The following day came another update, again described as a reprint of Grant’s words in Scotland’s leading regional newspaper - and it contained an absolute bombshell.

When Herschel had pointed his colossal instrument at our humble Moon and peered through it, he’d found a living world.”

19. Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast (Paid Subscribers Only)

“Does this turn wonder (and curiosity) into an obnoxiously vague “let’s all just hug it out” attempt to build common ground with things that gets lots of people riled up, allowing people like me to appeal to both sides in a cowardly way on many important issues just so we can get a big audience?

Uh - maybe? I mean, it might be. I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t considered it.

But what if it’s actually something more?

What if a sense of wonder is actually something everyone can agree on, and that everyone needs to thrive? What if, instead of arguing over the validity of often incompatible belief systems as applied to each other, it’s worth considering and respecting the value of triggered, felt wonder as a vital, useful thing in itself, however it’s derived - and consider the effect of it (along with awe and curiosity) in creating meaning, compassion, empathy and understanding between people … including the kind that can create good, positive change in the world?”

20. Look. Look. *Look*.

“The examiner says: “Everton, where’s the London Edition Hotel?”

This question, and the following ones like it, requires him to remember specific locations from London’s roughly 100,000 landmarks. He has to know where these places are - and he has to know how to get there from anywhere else.

“OK - how about Battersea Reach?”

“Uh…that’s on…Juniper Drive?”

“Correct. Now tell me the quickest way from London Edition to Battersea Reach.”

Now Everton has to assemble and recite this route from memory, taking into account everything that might affect the journey along the way. A 5.9 mile section of the roughly 25,000 streets that run across London, rattled off the top of his head without hesitation…

This kind of problem-solving is what the famous London black cab drivers do in their heads, in the time between you telling them your destination, walking round the back of the cab and settling into your seat. That’s the requirement to get the certification that lets them operate a black cab, and it’s been the requirement since 1865. This test was tough to start with, but a century and a half of road-building later, what it’s evolved into is an incredible feat of memory and spatial judgment under pressure.”

21. Antonia Malchik Is Exploring How We Own The Land

“Early on, I remember just really immersing myself in all those wonderful travel writers that I'm sure we both read and love and follow and wish we could be - and I got to the point where I realised that some of the best travel writing I really like is place-based. And then you see a writer who's kind of stereotyping people, or doing a competent job but it's still characterizations that are ‘other-ising’?

I've seen it happen about Montana so often - they send someone out from a national newspaper because…okay, a real example: there's this great bar in the city where my grandmother used to live, which is over on the more plains and farmland part of the state, not in the mountains. It’s a funky little place. A newspaper, I think it was the New York Times, sent someone out who wrote this story about “life in Montana.” And they wrote stuff about this bar that I’m sure they thought was funny but it was awful. It felt dumb and silly.

When you see the way that they describe a place that you know really well, and the people you know really well and you're like, ohhhh, that's what we do to other places.”

22. ‘Don’t Start A Newsletter’ And Other Advice For Newsletter Writers

“[I]f you don’t want to write about “the news”, you’re allowed to not write about it without feeling bad about it. Seriously. Because I know how easy it is to feel bad in that way. So you really care about ferns, or earthenware teapots, or the poems of Sappho, widely agreed to be one of the greatest poets of Classical Greece, and you absolutely burn to explain to everyone else why they should care like you do. Well, you’re allowed to do that. Even with climate change, the war in Ukraine, governmental corruption, amazing displays of idiocy from people in positions of great power, all these other things in the news - you are allowed to write about your specific nerdy thing.

Two reasons for this. First: because your nerdy thing has value, and that value can’t be erased by cheap, lazy comparisons to other things. You know this deep down - it’s why you care so much - but the desperate noisy urgency of the rest of the world can easily drown it out.

Social media’s made this much worse: oh look, this really awful loudmouth spouting nonsense is trending, that must mean the world is filled with really-awful-loudmouth-supporting dimwits. Or - they’re trending because everyone’s yelling at them, and in fact nobody gives a toss about them and would much rather talk about teapots, if only someone would start doing that properly.”

23. Behold The White Cliffs Of Megaflood

“But the English Channel? Oh come on. This is the UK. Things have a habit of not happening here (earthquakes, volcanoes, revolutions, tolerable weather, displays of genuine emotion). That’s what it’s famous for! What could possibly happen here that could be labelled High Drama?

Well, one answer to that question could be “everything in our politics since 2016” - but the more considered and relevant scientific response is “everything happens everywhere, if you give it enough time.”

And this is how I learned that around 425,000 years ago, the island of Great Britain was wrenched away from Europe in a fashion more dramatic than the fevered dreams of any hardline Brexiteer, by a single flood so violent that it could part continents.”

24. Three Ways That Kindness Can Save Us All

“This is a science-based story that convinces because it shows what happens when people find a way through some recognisably chaotic times by finding ways to work together. By showing each other kindness, and forging a spirit of cooperation from it.

If For All Mankind has a message, it’s we get there together or not at all. There are no perfect heroes, and no outright villains. People make mistakes for all the richly human reasons a character drama is fuelled with. And when that happens (which it does, to everyone), they’re not alone when they pick up the pieces of the mess they made.

And the end result (spoilers!) is that everything keeps moving forward: imperfectly, contentiously, but unmistakably forwards.”

25. Rare Skies And Turning Tides

“These rare Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds showed up over Wyoming on Tuesday, in as perfect a display of fluid-like atmospheric physics as you could ever hope to see.

They looks like waves breaking because - they’re waves, breaking. Much the same fluid dynamics equations are at work as in our seas, giving a slightly unsettling reminder than we all live at the bottom of an ‘ocean’, except it’s made of air, not water.”

26. Five Weird Ways To Enjoy Witching Week

“This is stolen from adventurer Al Humphreys, and it’s really simple: you take some form of local public transport, but you only buy a one-way ticket, because you’re hoofing it back home.

The joy of this isn’t really the walking (although a walk of any length is certainly a fine thing) - it’s really the perspective-shift it gives you. It turns that distanced, TV-like blur of terrain outside the bus or train or car window of your regular commute into an Actual Place You’re Actually In. You can hear it. You can smell it. It’s an unexpected party for the senses.”

27. Why Space Is Wet (And So Very Far Away)

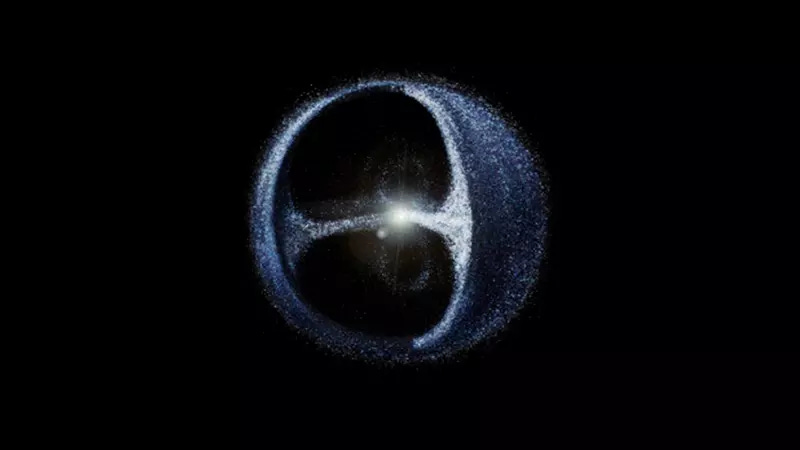

“There’s no real way to visualise this thing, but here’s one artist’s attempt to at least get the idea of it across in a way that fits into our brains.

The utmost rim of our solar system, more or less everyone agrees, is the point where the Sun’s gravitational pull is negligible compared with that of the other stars in our galactic neighbourhood. And within this boundary should drift an essentially unimaginable amount of fragmented rock and ice, forming billions of comets and trillions of asteroids.

All this stuff drifts around according to the mathematical elegance of the laws of gravitational force. You can see them at work in the image above: an inner “cloud” in the form of a faint torus (or upended infinity-sign, appropriately enough), surrounded by a far larger outer ring in the shape of a scaffolded bubble - or, to my eye, the former Cardassian mining outpost of Deep Space Nine.

It’s called the Oort Cloud, after the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort - and nobody has seen any sign of it yet, even though its existence is not currently in dispute.”

28. Open Thread: What Do You Wish More People Were Curious About?

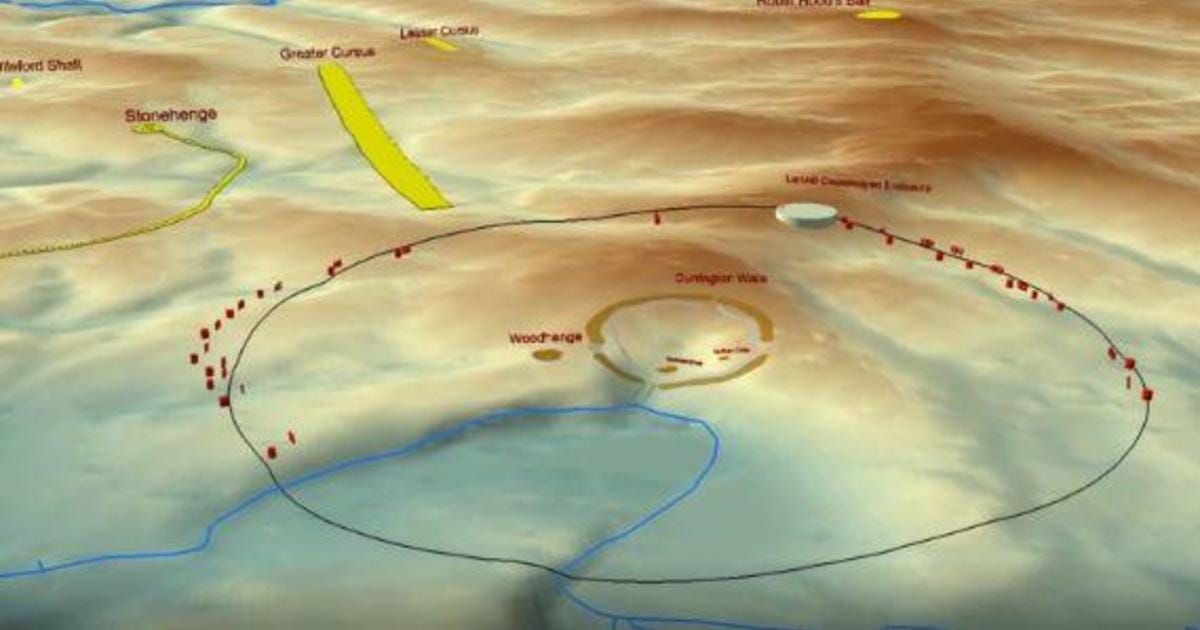

29. The Curious Idea That Ancient People Weren’t Dimwits

“I don’t personally know if people in general have always been just as smart as they are today, and I’ve barely started doing my reading into the research on it. If I find credible research suggesting that people in the Neolithic were as dumb as the rocks they used to build things, I promise I will report back. After all, science is about following the evidence, and this newsletter is about following the science.

But starting with this assumption is important. Because: what happens when you value-judge something, when you say “people in history were morons”, or even “people today are morons compared with history”? Well, you rank them. You say “this is better than that” - and in doing so, you put one in a category of being less interesting than the other. This stops curiosity dead. It just kills it. But if you assume people exist on a level playing-field of interestingness, it’s much easier to get curious about what you don’t yet know about them, including their seemingly “weird” behaviour.

So really, this is about the way we treat difference. Different ideas, different technologies, different beliefs, every difference under the sun. Instead of immediately ranking difference (which is a curiosity-killer), we can respect it. Or at least try to. Value judgements are so deeply hammered into us that this is phenomenally hard. Just read, I dunno, someone’s Substack about music. But we can try, because ultimately it will help us understand difference better.

And one way we can do this is by assuming that people in history weren’t any stupider than we are.”

30. The Magic Of Everything Everywhere All At Once

“…when, 45 minutes in, the film seems to be saying Hey, what if we're the products of all the wrong possible choices in our lives? - it’s a real gut-punch.

But that’s not what the film ends up saying at all. It’s out to say something trickier, deeper, much kinder and far more hopeful. Something about the corrosive nihilism of measuring ourselves against what-ifs until we’ve lost all sight of what actually is. Something about engineering joy, not just waiting passively for it, or blaming others for its absence. Something about having hot-dogs for fingers. (I know, I know. Just - watch it!)

But it’s also about how exciting it is to step into other versions of yourself, where you can discover different skills, different experiences, and where you see the world differently in so many ways - and, ultimately, it’s about how it’s never too late to do that, including when you’ve spent your entire life not doing it.”

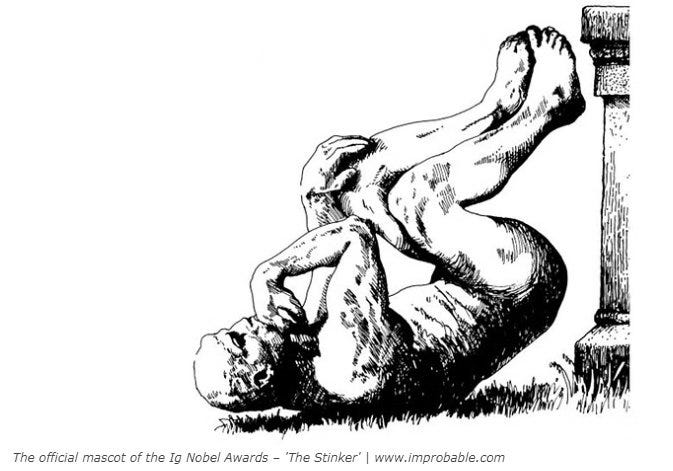

31. Making Them Laugh, Making Them Think

“Almost all the winners are being invited in, to share the joke and poke fun at themselves - while knowing the fun is good-natured and not actually disrespectful, since everyone understands that Actual Science happened here.

And sometimes, that work is really good. In 2000, Sir Andrew Geim was joint-awarded the Ig Nobel for Physics, along with Michael Berry, for their work in levitating a frog using diamagnetism. Ten years later, Geim would joint-win the actual Nobel Prize for Physics for his work with the carbon allotrope Graphene, a material that’s currently making headlines for how it’s unlocking all sorts of new scientific breakthrough.

But the Ig Nobels are also intentionally daft. They make a priority of aiming for a LOL - like how, in the very first Ig Nobel ceremony in 1991, then-US-Vice-President Dan Quayle won in the Education category “for demonstrating, better than anyone else, the need for science education.”

(I also love their description of him: "consumer of time and occupier of space.")

It’s about using humour as a tool for positive change - to shine a light on scientific research that’s quietly doing fascinating things, while also pointing out the deeply hilarious ridiculousness of…well, everything, really?”

32. The Fun Is Why

“This is really about what I call the tyranny of usefulness: where the value of doing a thing, the “sense” bit of “it has to make sense”, goes back to two things.

Firstly, the old economic-based model of productivity that’s been haunting us since the industrial revolution - does it help me produce more widgets and therefore make more money and maybe help me retire a bit earlier? You know: “useful” stuff, not for “fun”.

And secondly: we can quantify the usefulness of it in advance. We’re doing it because we already know what we want to get out of it.

But here’s the thing. As I hope I’ve demonstrated over the last four and a bit seasons of this newsletter, there is great value in discovering things you never knew you didn’t know. It just feels great, and opens your mind in all sorts of ways - including so-called useful ones - to realise the world is filled with more interesting and even more joyful stuff than you ever could have guessed.”

33. This Is How You Create Stuff And Sell Lots Of Books

“Three days ago, a person on Twitter called “bigolas dickolas wolfwood” posted a picture of the book cover along with the words: “read this. DO NOT look up anything about it. just read it. it's only like 200 pages u can download it on audible it's only like four hours. do it right now i'm very extremely serious.”

This tweet, with all its infectious, mystery-driven enthusiasm, went massively viral, as fans of the book leapt in to yell about how great it is, pushing it in front of millions of new readers.

The book rapidly rose to being, late last night [deep breath] the 7th bestselling book of ALL BOOKS ON AMAZON.”

34. Science Fiction Helps Us Ask The Hardest Questions (second half of interview with Antonia Malchik)

“Sometimes you just get really stuck on a huge writing project and my strategy is to go for walks instead of trying to glue myself to my desk. I'll go for a long walk around town thinking, How can I actually demonstrate this idea with an example that helps people feel their way into it? And then something will (hopefully!) come, like, Oh, there was that scene in The Expanse where the Marine from Mars is trying to walk outside on Earth for the first time and she's having such difficulty doing it. You can make it a relatable shortcut. I realized I could play around with that kind of thing–using science fiction to demonstrate some of the more granular biology and mechanics of walking–and see what my editor says, and she didn't seem to mind it. So I kept going.

There's a lot in that story, The Expanse, that talks about things I'm working on, like the commons and private property and management of resources. In The Expanse it's right front and centre because the people who live in the Belt [the real-life asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter] don't have reliable water sources, and they're dependent on other people for air, and are forced to live in a colonial-type situation in relation to the far more powerful nations Earth and Mars that they didn't choose and don't want…”

“Ozone forms when lightning rips the air apart to form oxygen and nitrogen, leading to the formation of nitric oxide, which is important to biological health (Molecule of the Year in 1992!), and conventional oxygen (O2) - and, every now and again, ozone.

You’re smelling it because of an enormous downdraft of air that comes before a storm, which drags ozone down from higher altitudes. What’s filling your nostrils is the aroma of the atmosphere 20 miles above your head - if it wasn’t so cold up there that your nose would immediate freeze solid, of course.”

36. Open Thread: What Would You Do With Your Nerdiest Year?

37. The (Mostly) Forgotten Battle For American Independence…In Yorkshire.

“Let’s imagine you’re standing here on a September night 244 years ago, looking out to sea.

The cliff behind you booms with distant cannon-fire, as the newly-minted United States of America fights for its independence a couple of miles offshore.

What’s happening out there is heroic, exciting and faintly ridiculous. Thirteen British colonies in North America, 3400 miles away, have decided they’ve had enough of Britain’s outrageous nonsenses, and they’ve declared independence.

That’s not the ridiculous bit, of course. What’s ridiculous is that an American Continental Navy squadron is fighting the British here, off the coast of Yorkshire.”

Back tomorrow with details about where we’re going next! And thanks so much for reading.

- Mike

Main image: Simon Berger

![The Expanse Actor Frankie Adams Talks About Bobbie's Most Memorable Season 6 Scenes [Interview] The Expanse Actor Frankie Adams Talks About Bobbie's Most Memorable Season 6 Scenes [Interview]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WIPy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6f0d2546-0d3e-43fe-9097-db2bdabefd7c_780x438.jpeg)

Such a great season, Mike! Thanks so much for giving me something to look forward to and inspire me in my own writing every dang time!

I’d forgotten how much fun this all was! Thanks for the great work you do, Mike. Awesome!