Plastic Rocks And Technofossils: Why New Geology Is Getting Weird

But: we say "pollution," they might say "opportunity".

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, an excitable romp around some surprising corners of modern science (like impossible colours, underwater cities and inverted Adeles), in the hope of stumbling over a good “wow!” or two.

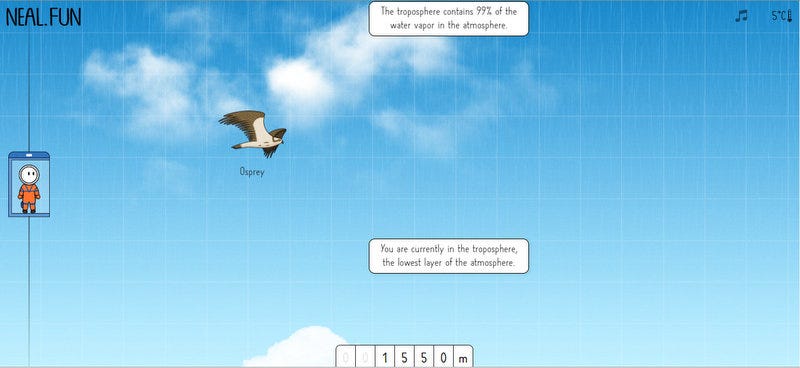

First up, please click this link - and if you spend the time scrolling through its delightful depiction of our atmosphere that you would have spent reading this newsletter, I’m pretty okay with that:

(Hat-tip to finder-of-great-things Brendan Leonard, who featured it in his recent Friday Inspiration roundup, after spotting it at Kottke.)

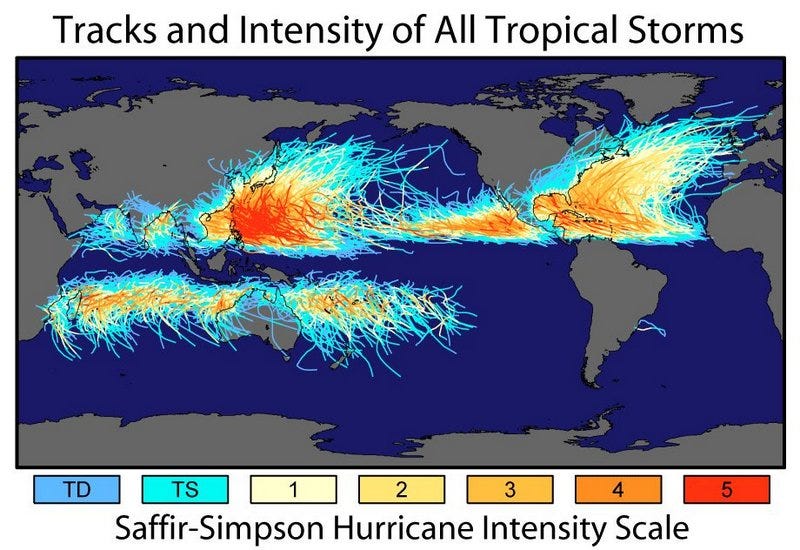

Secondly, a startling thing I learned recently: it seems no observed tropical storm has ever crossed the equator.

In theory one could, if it grew big enough to overcome….well, whatever is stopping such storms from crossing the equatorial boundary. Atmospheric scientists seem to still be chewing this over, but the Coriolis Effect might be a big factor? If you know more on this than I do, please correct me!

(They also don’t seem to form within 5 degrees of latitude of it. So, if you suffer from Lilapsophobia - that’s a fear of hurricanes and tornadoes - then moving to somewhere smack on the equator and never straying 5 degrees of latitude in either direction might be worth a try? Here are some countries you can pick from.)

And lastly, an update on a previous newsletter. Remember I wrote last season about the 20,000+ underwater mountains that were discovered a decade ago (which Bad Astronomy’s

covered for Slate here)?Thanks to the latest edition of Jodi Ettenberg’s Curious About Everything, I just learned about this newly-mapped monster:

It’s called the Pao Pao Seamount, it’s in the South Pacific Ocean - and it’s 4,776 metres tall (around the height of Mont Blanc), making it one of the tallest fully-underwater mountains ever discovered. It’s part of a collection of sea mounts recently mapped by radar and newly catalogued by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

But what’s so staggering is not just the presence of one-off wonders like this - it’s the sheer number of these things. The catalogue has recorded 19,000 new mountains, added to the 20,000+ mapped in previous surveys - and it’s estimated that the “vast majority” still wait to be discovered.

(As I said last season, it’s truly awe-inspiring how little we know about the 71% of our planet currently hidden under water.)

Anyway!

In today’s edition, we’re looking at the other part of our planet logically named Ocean Earth.

Continuing the season-within-a-season on the ways geology affects every single part of our lives (right down to the amount of rain that lands on our heads), let’s look at one aspect that’s staring us right in the face every single day.

Wherever you’re reading this newsletter right now, you’re probably doing a fairly bizarre, possibly uniquely human thing with your surroundings.

Perhaps you’re indoors, sat on your favourite chair, your legs curled under you - or you’re at the breakfast table, or in bed, because pretty much the first thing you did this morning was grab your phone and check your email, where this newsletter was waiting for you. (Yeah. I do that too. So we both have a problem here.)

Maybe the sun is shining, or maybe the rain is belting against the window. Whatever’s going on, you’re comforted by - or maybe slightly annoyed by, if it’s sunny - your awareness that you’re currently inside.

Have you ever considered what a strange human invention “inside” is? That poorly defined place where we pass over some kind of threshold - usually a door, perhaps a window during emergencies - where Public is transformed into Private, and Everyone’s becomes Yours, and the illusion of predictable, vaguely law-enforced safety descends comfortingly around you.

I’ve written elsewhere about how tents trick us with the fairly ludicrous illusion of inside-ness, but it’s the buildings within which we make our homes that do a much more credible job of it. They’re sturdy, for starters. Get through THAT, yells the average wall. Doors are meant to keep stuff out. Windows are for seeing the outside through, or for pulling the curtain or blind over to banish it completely.

Psychologically, when we’re indoors, we feel like we’re in some profound form of Elsewhere - when a coldly rational part of our minds know we’re actually just inside some kind of box by the side of a busy street (which is also lined with other boxes containing other people).

That’s pretty weird, if you think about it long enough. Open up Google Maps and check out your current location. Look: you’re there. Now try to tally that up with how your surroundings actually feel right now. Are you fully aware of what’s beyond those walls on all sides? What’s your sense of connection with everything actually surrounding you right now, based on a satellite’s bird’s-eye view?

(How far is it to your nearest neighbour that you’ve never said hello to? If it’s shockingly close, try doing challenge number five here, just to see how much you can freak yourself out.)

There are many varieties of Inside that we occupy - like public transport, or our car, or that bus shelter you’re hiding from the rain under, where you’re suddenly oddly resentful of the arrival of a stranger (“hey, get your own!”)…

But nothing feels more Inside than the inner spaces of our home. It’s our most intimate, most familiar, most emotionally comfortable place in our lives, where we can fully let our guard down, and where we feel confident of being masters and owners of our terrain.

For this reason, nobody knows our homes like we do.

Except - are you really sure about that?

Okay. Let’s test this out.