Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, awe, wonder and strategically stupiding up your whole year.

It’s been over a month since the fourth season wrapped (here’s a summary), and I’ve been on a break, spent alternating between reading books, catching up with Better Call Saul (what an incredible finale!) and throwing myself in the sea to stay cool.

(I’m also running half a week late here because of a nasty cold - not, I think, The Dreaded Virus, but certainly enough to knock me off my feet for a few days.)

But I’m back at last - and season 5 begins in the next newsletter coming your way. (If you didn’t see it previously, here are the details.)

Let’s hope I do a better job of assembling it than this:

(Yes, it’s real - and it has an amazingly complicated history.)

But today, introducing the new season-within-a-season I’m running only for paid subscribers on how the land under our feet shapes our behaviour, I’m looking at the reverse: a modern attempt by humans to fake the work of millions of years of geology in order to bend the atmosphere in a new direction.

Because I’m sorry, they want to build a what?

Sometime around early 2016, the United States National Center for Atmospheric Research received what might have looked like a very strange request from the government of the United Arab Emirates.

Could they help them build a mountain, please?

More specifically: by way of a $400,000 grant, could they help the UAE research the potential environmental impact of building an artificial mountain somewhere in the country?

It’s certainly not the oddest proposed engineering project for this region of the world. Just look at the ones that were actually built, like Dubai’s Burj Khalifa (at 829.8 metres, it’s the tallest building in the world), or the Palm Islands artificial archipelago.

Or look next door, at Saudia Arabia’s Neom project, complete with a futuristic ski resort, and a proposed 170-km-long mirrored skyscraper canyon-megacity. (No, I’m not making this up, and yes, it seems they’re seriously having a go. For the reasons Elle Griffin lays out here, there might be some impressive upsides to it - although the great human love-affair with the automobile seems to be smack in the way…)

It’s not hard to find something here to be critical about - say, the appalling living conditions inflicted on migrant workers, or the ridiculous amount of money being thrown around (or wasted, depending on how you feel about it), almost all of it generated from selling petroleum and natural gas. It’s equally easy to conclude these megaprojects are cynical attempt to monetise super-rich tourists before the current fossil-fuel gravy train grinds to a halt. (I mean come on, Dubai: an airconned beach is not exactly hiding your intentions.)

But - a mountain, you say?

As Atlas Obscura notes, the world is already littered with artificial mountains, particularly the United States, in the form of construction spoil-heaps left over from cement and steel production. Many of these have been tidied up. grassed over and turned into something that looks like it was always there.

But really, most of these are just hills. Whatever the point is when a hill feels big enough to be labelled a mountain, these artificial constructions usually fall short of it. Making an artificial *mountain* is something on another scale entirely, requiring a mindboggling investment of effort, time and money…

Nevertheless, the UAE is looking into it. Of course it is. It already has a permanent weather modification department (which spends hundreds of thousands of dollars each year on cloud-seeding measures to encourage rainfall - most recently by zapping clouds with electrical pulses fired from drones, apparently with successful results). Why not go even further?

If this was just another version of Obscenely Rich Folk Flushing Money Down Their Gold Toilets, I wouldn’t be writing about this. Nuts to all that, considering everything else going on in the world.

But the proposed UAE mountain is actually a megaproject with a fascinating science-based difference - and that difference is presumably why a reputable organisation like the NCAR agreed to get involved.

If you live near a mountain, you’ll be used to the sight of rain.

It may not necessarily be falling on you, but certainly you’ll see a lot of it. Mountains are rainmaking machines: like hands wringing a wet dishcloth, a mountain forces moisture-laden air to rise until it’s unable to hold onto its water any longer, and dumps it in great sheets of condensed precipitation.

If a mountain’s tall and wide enough, this wringing-out is so thorough that negligible rain reaches the other side - and, even worse, the onward-moving, newly-dry air creates a downslope wind that sucks up moisture from the land underneath it, creating a double-whammy effect that can parch fertile land into desert.

Perhaps the clearest example of this is the island of Madagascar, off the east coast of Africa:

The island as a whole gets enough rainfall to ensure that the central and western regions aren’t all barren desert - but you can certainly see the difference in fertility along that thin, green strip of land to the east, where coastal plains give way to mountains that squeeze most of the rain out of the easterly winds before they head west.

(This picture is deceptively huge, by the way: the island’s longer than the distance from London to Barcelona.)

Human beings have understood the relationship between mountains and rain since…well, probably since they became human beings. And it’s been just over a century since the formal study of the atmospheric sciences (mainly for weather prediction) took off in academic settings…

And now, it seems some people are starting to regard mountains as tools. The kind we can build ourselves, to get the results we want.

Okay! Uh. (Yikes?)

One popular view on this: it’s absurd, arrogant and horrifying reckless.

Another view: yes, it’s a bit absurd, arrogant and horrifyingly reckless, but these are difficult times and we’ve already made a mess of many natural ecologies and the old corrective measures aren’t working and we need to try something new!

Because of its effect on rainfall, this kind of artificial mountain-building is an example of geoengineering, a scattered array of proposed and already-implemented technological interventions in our planet’s climate systems.

Some of them are pure science fiction at this point - like launching mirrors into space that would reflect away a few percent of the sunlight warming the Earth.

Others are already underway, like the release of iron particles into the oceans that boost phytoplankton growth and speed up the sea’s ability to lock up carbon. (As this article notes, we’re already doing this accidentally in the form of pollution - but it seems that in this case, our poor plantary stewardship may have a surprising upside that’s worth exploring further, albeit extremely carefully.)

All forms of geoengineering are, understandably, hugely controversial. Aside from the ethics of a rich corner of the world embarking on a project that affects every part of the globe (even if those changes are beneficial, which seems currently impossible to judge) - well, do we not have enough self-inflicted existential crises on our plate? What happens if a so-called corrective measure spirals out of control?

These are not trivial questions, and it seems they haunt even the most well-informed people working in these fields.

Take mountains and rainfall. Even if an artificial rain-focusing structure did work as intended, what would happen if the average wind direction changes? As climate change pumps more energy into the atmosphere, our weather systems will get more chaotic. Just because moisture-laden air used to come from a particular quarter, that’s no guarantee that it’ll continue to do so. What if regional wind-patterns shift, and suddenly all your agricultural land is in the rain-shadow of that lovely new mountain your government’s recently thrown up?

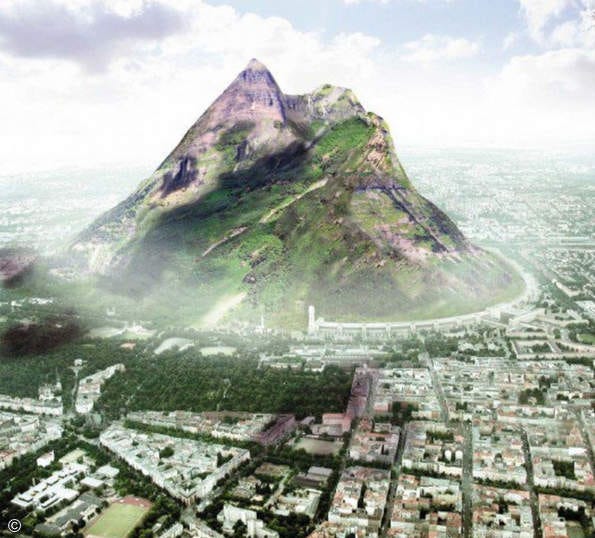

Did any of this occur to German architect Jakob Tigges when he proposed turning Berlin’s abandoned Tempelhof Airport into this?

A thousand metres high, The Berg would act as a natural habitat for mountain wildlife, a recreation space for the city’s residents like the park that the former airfield has turned into - and, perhaps, an enormous stick of dynamite lobbed into the path of Berlin’s weather systems? (No need to worry: despite its popularity with the public, The Berg was never greenlit for construction.)

This whole topic seems like one great big question-mark - certainly to my uninformed eyes, and also (alarmingly) to many of the experts working within it.

As the research is being done to understand it, the work is being pushed forward into the planning stages: sometimes fuelled by commercialism aimed at the mega-rich, and sometimes by the desire to seek solutions that could benefit everyone equally, in a way they’re most certainly not doing at the moment...

So. If humans tinkering with the land is such a thing (and it’s always been such a thing, right back to prehistoric forest-clearances, irrigation, hunting and the domestication of animals), then maybe it’s equally fruitful to consider how our the land tinkers with us. Specifically, how geography has driven us allegedly “free-willed” and “masters-of-the-Earth” creatures in all sorts of interesting directions since the beginning of our history, and how it’s still going on, to the extent that we’re now considering inventing large-scale geography to help us survive.

That’s the topic of this sub-season of Everything Is Amazing, running underneath everything else, and visible only to you paid subscribers.

And - it’s a lot. I’ve discovered that the little I learned from studying landscape archaeology at the University of York twenty years ago is even littler than I thought. This is a topic that pulls in geology, the atmospheric sciences, sociology, economics, politics, behavioural psychology, cosmology - all the ‘ologies, I suspect, if I let it get that much out of hand.

But I won’t. This is too much to bite off, so to start with, I’m going to try to answer a specific question that I really, really hope a lot of researchers in the UAE are studying in detail right now:

How do you really build a mountain?

I mean, what exactly is a real, properly-assembled mountain, in the natural sense we understand (and also don’t understand)? How different are mountains, as environments in contrast to everywhere else we live? And what do mountain do to us - and what have they done to us? We’ve already seen they change our weather. What else is within their power? How do they affect us as individuals? (Fascinating field of study!)

In short: how have mountains built us - even those of us who feel like we’ve spent far too little of our lives surrounded by them but are obsessed with them anyway, (because for some strange reason pretty much everyone is)?

Considering we spent a lot of last season exploring the mountains at the bottom of the sea, this feels like an appropriate next step.

So that’s our way forward. Let’s see what’s up there.

Images: European Space Agency; NOAA; David Rodrigo.

Mountains that created themselves usually follow the general rules of isostasy/isostatic equilibrium and have a "keel" sticking down into the mantle- what would all that weight do to the crust if a mountain were built up, and what about the crust rebound from where the material was sourced? oh man, so many questions!!

This whole post just gave me chills! Thrilling in all sorts of ways. And, being a born and raised mountain girl myself, the whole topic of how those kinds of landscapes affect our psychologies is a fascinating question to me. This will be so fun!

I was looking at that long, skinny mega-city plan and all I could think about was a wall in wildlife migration patterns. Assuming there are wildlife migration routes that would be affected. I guess if China managed to build that gargantuan dam that measurably affected the planet's gravitational balance due to how much water it displaced, someone else can build the most absurd city in a desert ...