Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity, wonder, and how ancient people weren’t as daft as we might think.

If this kind of “wow, I never knew that!” sciencey stuff is your thing, pluease sign up for free below to get more of it:

Okay. Let’s bend your mind until it breaks.

Warning: if trying the following makes you feel genuinely uncomfortable - say, the sudden urge to puke, or perhaps track me down and kick me in the unmentionables - then please stop doing it! I promise you won’t miss anything, since I’m going to explain the whole thing as I go along.

Do you remember those “Magic Eye” (autostereogram) images that were all the rage in the late 1990s? The following works in a similar way.

Pick one of the two horizontal pairs of coloured squares in the image above, and fix your gaze on the white cross in the centre of one of them. Now let your eyes relax and unfocus, and gently try to cross them, as if you’re focusing on the tip of your own nose, except you’re still trying to keep that white cross in view while you do it.

Do this until you find a way to superimpose both the white crosses in each of the two squares over each other - bright red square snugly over bright green square, or darker red over darker green - and then try to keep them there.

(If you have any of the red/green colour visual deficiencies we called “colour blindness,” try this alternative with blue and yellow.)

If you’re like me, you’ll see the colour of that superimposed square flick from red to green (or blue to yellow) and back again, again and again, confusedly, as if your eyes can’t make their mind up or are panicking like a startled cat.

This is happening because you have presented your poor mind with an impossible challenge. It’s currently trying to blend those two colours together until you’re only seeing one image, in much the way our binocular vision has been helping us perceive depth since we were around 4 months old.

Except…

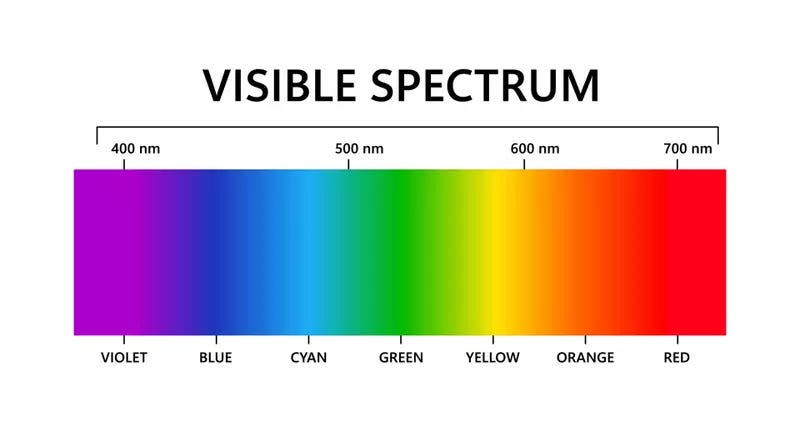

…red and green aren’t next to each other in the visible spectrum. There are two primary colours, yellow and orange, in the way - plus a vast array of different shades of each, representing hundreds of nanometres of different wavelengths of light.

On top of this, red and green are opponent hues - the colours which will form as afterimages against a white background if you stare at the other colour long enough. So your visual system just doesn’t know how to blend all of that together and “display the average” of the two opponent extremes of that scale: red and green.

So, naturally, it’s freaking out.

Be sure to enjoy this! Give it a few more seconds. Let it claw at the walls of your sanity. People consume all sorts of expensive recreational substances to have experiences as perception-jarring as this.

If you’re most people, your mind will continue to chaotically flop about, switching from one colour to the other without settling properly on either, for as long as you perform this self-experiment. (In my case, I think I’m starting to see a sort of ‘brownish-but-also-not-really’ colour before it flips one way or the other - which is interesting, since brown is what results if you mix red and green paint.)

It’s a hard limit of your visual system that you’ll probably never be able to go beyond. Congratulations: the fail-safes in your nervous system are working perfectly! How reassuring.

But it’s possible that you’re one of a very small number of people who will see…something else. For whatever reason, your mind may have the ability to look beyond that perceptual event horizon, beyond the apparent limits of human optical architecture - and see something that cannot possibly exist in the real world.

Welcome to the strange, strange world of redgreen. (Or yellowblue.)

It’s a colour you’ll never be able to explain to anyone else, since no language has developed words that can capture it adequately. Like Concetta Antico and her alleged tetrachromatic vision, it seems you’re perceiving colours almost nobody else can see - although, as with Antico, modern science has yet to reach consensus about whether this is really happening in a measurable sense, or if you just have an unusually vivid imagination.

In an elegant experiment in 1983, engineers used an eye tracker to fix the subject’s gaze onto the centre of a series of vertical red and green strips. The tracker used mirrors that responded to the tiny involuntary eye movements called saccades that stop our vision from becoming so stimulus-exhausted that we start hallucinating, as I previously wrote about here. No matter how their eyes moved, they still saw precisely the same image - counteracting the ‘screen-refresh’ (or, if we’re reading a book, ‘carriage return’) effect of a saccade.

For a few people taking the test, the view appeared to be absolutely wild:

“Some observers indicated that although they were aware that what they were viewing was a color (that is, the field was not achromatic), they were unable to name or describe the color. One of these observers was an artist with large color vocabulary. Other observers of the novel hues described the first stimulus as a reddish-green.”

Reddish-green, of course, doesn’t make much sense as a description - unless you mean yellow or orange, which you don’t, because you would have said “yellow” or “orange”. It’s a weird thing to think about, let alone see, and I really hope that if such people really exist, you’re one of the lucky ones.

(Fun fact: I’m one of around 5% of people in the world with something called Voluntary Nystagmus - a benign version of a very unpleasant eye condition - where I have the ability to make my eyes move independently of each other, if I so choose. I’ve been horrifying family members with it for the last 30 years - “do that bloody awful thing with your eyes, Mike! Jack hasn’t seen it yet!” - and I’ve never found a potential use for it until now. So instead of crossing my eyes inwards on each of those coloured squares, I tried moving one outwards, so I was simultaneously looking in two directions. By fixing each eye on one coloured square, each separated by a much larger gap than in the above image, I thought I could trick my brain into doing something amazing! Alas. What I saw was two images oscillating between each other, which eventually resolved into a Costa barista asking me if I was OK. Experiment over.)

OK. So you probably didn’t just see an impossible colour. I’m sorry, and I hear you: it’s very annoying when impossible things refuse to exist.

So here’s a better way for you, and just about everyone, to see not just one impossible colour, but three of them.

The way it works is simple, and you can do it three times, one for each row (giving your eyes a bit of a break in between doing each one).

First, you stare intently at the cross in the centre of the coloured circle in the column named “fatigue template” - then after maybe 30 seconds, or after as long as you can hold it, you dart your eyes sideways and stare at the cross in the “target field” box.

Have a go!

…

…

Okay! All done? How did you get on? And did you notice anything really weird about those colours?

Let’s take the first line: the apparent dark blue circle superimposed on the black background of the target field. Did you notice how it somehow looks darker than the black background, and yet it’s blue? But black is the absence of colour - it’s where colours go to die. You can’t darken black and end up with a colour. Beyond blackness is, well, just more black.

In the real world, this category of none more black includes the incredible Vantablack, a coating made of carbon nanotubes that’s capable of absorbing up to 99.965% of visible light, making it look like a hole in the world that’s so deep that not even a laser can reach the bottom of it:

But somehow, you saw a colour darker than black. It’s called Stygian Blue (from the mythical river Styx, with its waters darker than darkness itself) - and you certainly saw it, even though it’s not really there.

When you tried the second row, imposing the afterimage of that green circle upon that white background, you should have seen the exact opposite effect - a glowing pale red that seemed even brighter than its white backdrop. Which, again, is nonsense: white’s an infinity of colour, where optical colours go to die in the other way, being drowned out of existence by the sheer amount of mixed colours present.

In terms of optics, you can’t go beyond white and find a dominant colour other than “even whiter super-white”. In the physical world, that honour probably goes to this new paint that reflects 95.5% of sunlight, with exciting potential for keeping buildings cool without turning on the aircon.

Except - there are indeed real-world things that appear brighter than perfectly white surfaces! For example, we light our homes, our streets and our cities with one type of them. Anything that emits light has the potential to outshine a reflective surface - and that’s what seems to be happening here with this oddly brighter-than-white red circle.

For this reason, it’s a form of impossible colour called Self-Luminous - even though it technically isn’t, it only seems luminous.

The third row is the weirdest of the lot. The afterimage of that cyan-coloured circle, according to Opponent Process Theory (more on that another time, because it has delightfully absurd implications for how we see the world), is orange. But when you project that afterimage on that already fully orange square to the right, your brain is presented with a dilemma: hey, what’s even more orange than Totally Orange?

The answer is what you can see (or rather, think you can see): the gloriously named Hyperbolic Orange.

It’s like a colour version of the amplifier belonging to Spın̈al Tap’s Nigel Tufnel, with the dials that go up to eleven:

It’s complete twaddle (like Tufnel’s explanation), but it’s twaddle that temporarily fools you into thinking it’s ‘one more orange’.

The collective name for these three hues is Chimerical, from the word meaning “impossible to achieve,” because - yes, that. (Sort of).

Almost everyone should be able to see chimerical colours - unless the photoreceptors in their eyes are used to doing things a little different from the norm - and they’re another glimpse of the borders of our visual comprehension, where we abandon the science and give way to the realm of dream, hallucination, fiction and fantasy…

“The Neathbow is the collective term for seven colors which cannot be seen on the Surface…

The seven colors of the Neathbow are irrigo [“the unremembered color, the light of absence”], violant [“the color of troublesome but necessary connections”], cosmogone [“the color of remembered sunlight”], peligin [“the hue of the waters of the Unterzee and those of the land of the dead”], apocyan [“the color of coral and memory”], viric [“the green of shallow sleep”], and gant [“more beige than one might expect”].”

- The Fifth City, the unofficial wiki of Fallen London

“I put on the cloak... the hue fuligin, which is darker than black, admirably erases all folds, bunchings and gatherings so far as the eye is concerned, showing only a featureless dark.”

- The Shadow Of The Torturer by Gene Wolfe

“It was octarine, the colour of magic. It was alive and glowing and vibrant and it was the undisputed pigment of the imagination, because wherever it appeared it was a sign that mere matter was a servant of the powers of the magical mind. It was enchantment itself.

But Rincewind always thought it looked a sort of greenish-purple.”

- The Colour Of Magic by Terry Pratchett

(In real life, “octarine” was a proposed name for one of four new elements discovered and confirmed by the International Union of Applied Chemistry in 2016, and the subject of a widely publicised campaign - alas, an unsuccessful one. Next time, fans of the late Sir Terry...)

Further Reading:

- ““Impossible Colours”: See Hues That Don’t Exist” - Vincent A. Billock & Brian H. Tsou, Scientific American

Images: Zowie/Wikimedia; ISFDB; A Pilgrim In Narnia; Spooky/JPxG/Wikimedia; Uriel.

Very interesting. I had one other thing happened you didn't mention. While I stared at the yellow circle in the first row, the green circle below kept flickering in and out of existence.

THIS MEANS I HAVE A TUMOR, DOESN'T IT? HOW LONG DO I HAVE, MIKE? HOW LONG?!?!?

Mike, this was really fascinating! Stygian Blue really blew my mind. I did that experiment a couple of times back to back just to experience it a few more times.