The Curious Idea That Ancient People Weren't Dimwits

"I think about it when I dream - the biggest henge that I have ever seen."

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, science, attention and wonder.

In a moment I will be speaking at you about empathy in history, using my bargain-basement Game of Thrones accent - but before that particular rusty sword descends, here are a few merciful distractions.

If you enjoyed this interview with the wildly curious Anna Brones from the first season of EiA, or this three-parter on stillness with the ridiculously accomplished Candace Rose Rardon, rejoice - they’re both writing new newsletters on Substack!

Anna’s brought over her long-running publication Creative Fuel…

…and Candace is nurturing her creative mojo after some major life changes in Dandelion Seeds:

It’s also the one-year anniversary of my biggest life-change as a writer - a Twitter thread that somehow blundered its way out of my usual circle of friends and raced off to bother around 10 million people, exploding the readership of this newsletter along the way:

(Mad, all of it. Took me weeks to learn how to put my phone down again.)

Anyway, to things!

Today I’d like to turn the clock back, to a time when life was simpler and more carefree, when technology was little more than banging two rocks together, and when people didn’t have much to worry about, because they just knew a lot less. Right?

Welcome to a history that…never actually happened?

In 1996, I took my first extremely nervous steps into professional archaeology by going on a training excavation to a place called Bignor Roman Villa in West Sussex, in the south of England.

To say I didn’t know what I was doing is an understatement: we trainees were instructed to bring our own trowels, which in archaeology are small tools with a carbon-steel blade about 10 centimetres long. So when in front of everyone on the course I pulled out my newly-purchased bricklaying trowel looking something like a Star Destroyer fitted with a wooden handle, and everyone around me collapsed in hysterics - well, I can still remember how that felt. It wasn’t great, frankly.

But it got better. Archaeology attracts a lot of kind and generously-tempered people who are used to fielding questions from clueless idiots, so it wasn’t long before I was having fun again. And the profession was turning out to be just as fascinating as I’d hoped. Bignor, which was first unearthed in 1811, is a stunning sight, with some of the best-preserved mosaic floors ever found in Britain, and what was my first introduction to a hypocaust, a 2,000 year old heating system that circulates hot air under the floor so it’s warm under your bare feet on those bitterly cold mornings out here at the edge of the known world. Eeee. Luxury.

And Bignor was still being dug. After almost two hundred years, they were still extending the limits of the site to see what was nearby. With my inexperience of archaeology, I found this incredible. Two centuries and you haven’t finished? But surely there are others - how will you get round them all?

But what I didn’t know - and it’s a good job really, because it would have broken my tiny brain - is that hundreds of them are still under the ground.

In 2015, professional rug designer Luke Irwin decided that the old barn that was falling to bits twenty yards away from his farmhouse in Wiltshire would be a great place for his kids to learn to play table-tennis - so he asked builders to dig up the ground to lay some electricity cables.

And then: *clink*. That special sound of metal hitting a suspiciously unyielding surface, 18 inches down.

What emerged from under the whole property was a Roman mosaic belonging to a large villa, first built sometime between 175 and 220 C.E. covering an area roughly 70 metres by 70 metres, and containing three-storey structures, a well, a bath house and a stone coffin for a Roman child - Irwin didn’t know what this was, so he’d been using it to grow geraniums.

In the words of the archaeologist leading the investigations, Dr David Roberts: “this is not a subtle county house, it is very showy. It dominates the landscape, and it is visible from the nearby Roman road. It is very overt – it is almost violent in the landscape. It is clearly a family making their mark.” Yay for rich people.

This was an extraordinary find - but thousands of years ago, what we call Roman villas were themselves extraordinary, just an estimated 1% of late Iron Age and Romano-British settlements, based on projections of settlement patterns. This doesn’t sound like a lot, but that’s still thousands of villas and villa-like structures. A gazetteer from 1993 by Eleanor Scott of the University of Leicester lists over 1,500 “fairly good villa candidates” that have been discovered - but based on their continuing rate of discovery, there are hundreds still under the earth.

(One was found in 2020, in the early months of the pandemic, under a farm in Rutland in the East Midlands, complete with a mosaic depicting scenes from Homer’s Iliad.)

This is one of the great underlying wow!-s of practical modern archaeology: how incomplete it is, and how much has still to be discovered.

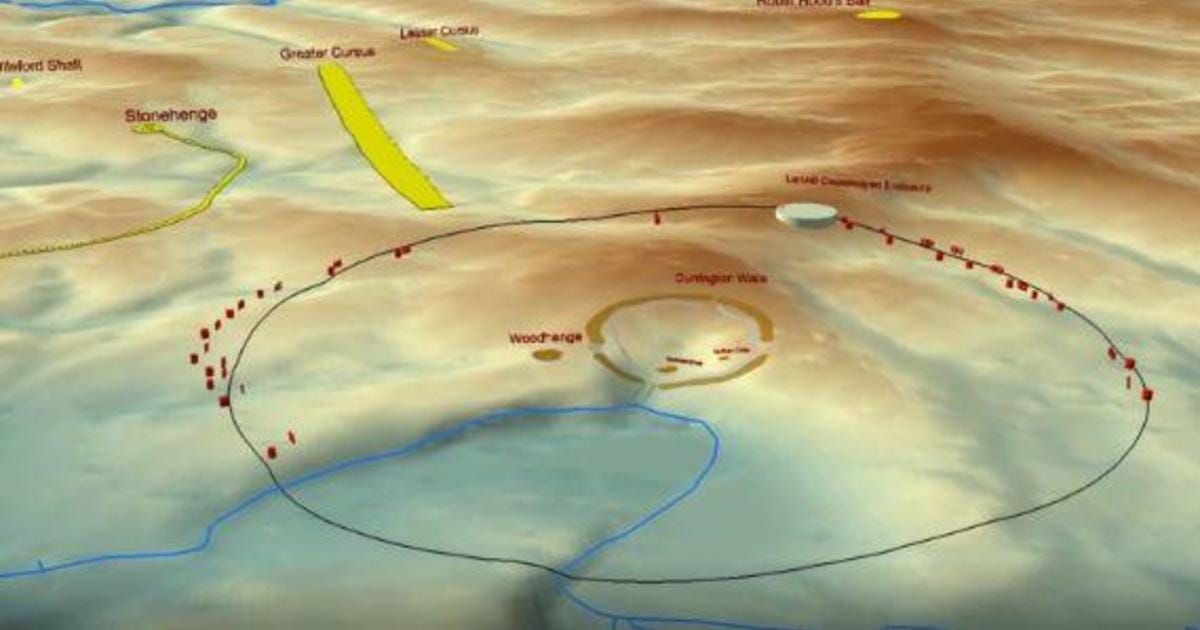

Take Stonehenge, one of the most famous ancient monuments in the world. You see the photos of it, you think “bloody hell, how did anyone miss THAT?” and of course, they didn’t, it’s been known about for centuries. But it’s also part of Salisbury Plain, which is a huge landscape of interconnected monuments and earthworks and cemeteries and middens and ceremonial walkways and barrows and all sorts of stuff, all connected in ways archaeologists are still trying to understand…

Oh, and of course there’s the superhenge. You don’t know about the superhenge? It’s quite near Stonehenge, it’s a long arc of buried stones and massive pits up to 5 metres deep, dated to the British Late Neolithic (that’s around 4,000-5,000 years ago), and the whole thing seems to be about 2 kilometres wide. And if you don’t know about it, that’s probably because it was only discovered in 2020.

How do you miss something two kilometres wide, in one of the most densely-populated countries in Europe? Very easily, if it’s still under the ground. The reason this was discovered at all was the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project (SHLP), part-led by Professor Vince Gaffney who was also recently involved in the project to explore the now-submerged plains of Doggerland, as I wrote about previously.

In other words, they were looking. And this isn’t just about digging up stuff, which is by far the least efficient way of covering lots of archaeology: it’s about mapping the relationships between things, to look for patterns of activity that suggest the locations of other monuments.

So really, it’s best to assume two things here. First: the overwhelming majority of ancient history is now lost to us. And secondly, a lot of what does still remain has yet to be discovered - meaning that archaeology is one of the most lively and wonder-filled sciences you could ever have the pleasure to be involved with. Seriously. Total blast.

But actually, let’s assume a third thing, because it’s going to help us understand the past a lot better, and to focus our curiosity backwards in time and downwards into the ground under our feet. It’s this:

“Ancient people weren’t stupid.”

A couple of weeks ago experimental psychologist Adam Mastroianni published this gloriously well-argued piece…

…in which he points out that our modern habit of associating seemingly irrational with stupid is, ironically enough, an immensely dumb thing to do.

I’ll urge you to go read the whole essay, it’s wonderful - but the following paragraph is particularly relevant for what I’m talking about today, where Adam’s talking about cognitive biases and how they’re not a sign we’re lacking in smarts:

“We should treat cognitive illusions like psychology’s other great export: visual illusions. These circles look like they’re different sizes, but they’re not! These rings look like they’re rotating, but they’re sitting still! These lines look tilted, but they’re straight! Visual illusions don’t prove you are bad at seeing. They prove that your visual system is doing tons of stuff under the hood to make you good at seeing, and specially-designed images can expose its clever tricks. Cognitive illusions do the same—they help us understand how the mind works by figuring out how the mind breaks, just with words and numbers instead of pictures.”

This is so perfectly said (and I wish I’d read it before writing the third season of Everything is Amazing, when I looked at optical illusions).

And in a wider sense, this isn’t just about being generous and respectful of the experiences of other people by not labelling them dumb just because we don’t know why they’ve done stuff - ie. empathic curiosity in action. It’s also about how to put aside the concept of “bad” altogether, because of its proven ability to get in the way when we’re trying to understand human behaviour.

So I’d like to take Adam’s line of reasoning in another direction - backwards in time, to that place where all those now-dead people did all those long-ago things we now mostly don’t understand.

For example, it’s so easy to look at something like Stonehenge and think “Why? Why did you do that? What’s the meaning of Stonehenge?”

And if you’re Norwegian and can sing and you’re… completely insane, you could make a song about that:

But it’s easy to turn that massive question-mark in your brain into some kind of judgement about how ‘unadvanced’ they were, which is another way of saying, they acted in ways that look dumb. “Well, people were simpler back then. Who knows? Just write something about rituals, Kevin, time’s marching on.”

Or maybe - no. Maybe people have never, ever been simpler back then.

How about we assume that every period of history and prehistory is filled with people who were just as smart as we are, and it’s just that they lived their equally complicated lives using different sets of ideas and beliefs and using different technology? Most of which we’re now unaware of?

This is a contentious field of study, where many cognitive scientists seem to be having all sorts of fun arguments. I gather part of the issue is a working definition of intelligence, which can get muddied up by our tendencies to equate so-called irrational behaviour as a sign of a lack of intelligence - where “irrational” sometimes means “we don’t understand why they did that.”

Think about how quickly that happens in modern life: “I don’t know why they did that —> I guess they must be idiots.” Particularly in politics - “I honestly don’t know why they voted for that bozo…”

(I’m reminded here of Mónica Guzmán’s work, if you remember that particular newsletter.)

But this seems to be a people problem. If we don’t understand a thing, we can conclude we’re missing something. But if we don’t understand someone, we tend to conclude they’re missing something. Our curiosity gets dragged in the wrong direction, because it’s been quietly drummed into us for decades that most people are, on the whole, idiots.

This is the issue that archaeology can correct, if you become a student in it, or volunteer for an excavation. If you’re like me you’ll turn up thinking it’s like a videogame that you’re already really good at, simply because you’re a supremely evolved modern human being, and you’ll immediately be stomped into bewildered ignorance by everything you’re desperately trying and failing to learn about how people did stuff in the past.

(My first excavation, like my first term studying archaeology at university, was terrifying. I thought I’d know something at least. But I didn’t. I knew nothing. And the reason was: holy crap, people are a lot of work, and they always have been.)

I think part of why this is so alarming is the way we’re taught at school. You learn the basics first, then you move on to the advanced stuff. But when it comes to human behaviour, nothing is basic. There are no basic people. Well…okay, there’s…no, leave it, Mike. Leave it.

So I’d like to invite you to see human history in a different way.

A few weeks back, I went to London for the day. This was a little foolish in that it’s an eight hour journey each way on the Caledonian Sleeper, so I spent 16 hours that day in travelling, on a sleeper train I almost entirely failed to sleep on. But it was well worth it, because I met up with Michael and Brent, of the Substack Brent & Michael Are Going Places, and we strode around inner London drinking coffee and putting the world to rights. It was a grand old time.

London is a fabulously complicated place, with so much to see. In my reading circle on Threadable this week we’re looking at a chapter of Helen Gordon’s Notes From Deep Time where she’s tracing the city’s geological roots in the sides of its buildings - a fascinating dive into ancient geology that’s clearly visible above street level…

Want to read along on Threadable?

- you’ll need an iPad or iPhone running iOS 12.4 onwards, or macOS 11.0 (apologies, Android & Windows users, Threadable are still in the early development stages here)…

- click the button below:

…after which it should automatically take you to my reading circle, now called “Active Geology with Mike Sowden”.

(If it doesn’t, trying signing in, going to “Home,” finding “All Circles” and swiping sideways until you find it. Request access, and as soon as I see your request, I’ll let you in.)

London’s also a place where everyone looks extremely busy and I never quite know why. I find that a nice feeling. It’s a reminder that beyond the immensely self-absorbed contents of my own head, the wider world of people is just getting on with their own lives and doesn’t give a damn about what I’m doing, which allows me to sit in a quiet corner, drink good coffee and read a good book in peace.

But also - London is full of Sonder.

Not the international accommodation rental company, and not the bike by Alpkit, but the concept they’re named after. It was invented by writer John Koenig for his website & later book The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows - and I’ve mentioned it before in this newsletter about kindness, but I’ll quote the whole thing again because it’s so gorgeous:

“Sonder — noun. the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own — populated with their own ambitions, friends, routines, worries and inherited craziness — an epic story that continues invisibly around you like an anthill sprawling deep underground, with elaborate passageways to thousands of other lives that you'll never know existed, in which you might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a blur of traffic passing on the highway, as a lighted window at dusk.”

Let me tell you, there are a lot of lighted windows at dusk in London. All those people trying to move forward, towards the story they want to live, woven out of opportunities and aspirations and big dreams and hard reality and what they ultimately want to do and what they temporarily need to do.

In other words, just as tangled as yours and mine. Millions of lit windows, with all of that going on behind them, and we are nothing but a faint blur in the distance - hardly worthy of a squint.

It’s relatively easy to wander through modern London and feel this. Or any big city you don’t live in. So why is the London of Charles Dickens or Florence Nightingale or Henry the Eighth any different? Or the London that Boudicca burned to the ground in 60 or 61 CE? Or of the settlements on the coast of England in the wake of the inundation of Doggerland? Anatomically, these are human beings in essence no different from us. The shape of the human brain became what we’d now call “modern” around 100,000 years ago - an expanse of time that easily guzzles up all of human history and about a third of our prehistory as a single species.

We’ve always had the capacity to think this deeply. And so, we always have. We’ve always been this anxious, this self-contradictory, this driven by our emotions for good and for bad - and on the whole, we’ve we can assume we’ve always been this smart.

The important word here is “assume”. I don’t personally know if people in general have always been just as smart as they are today, and I’ve barely started doing my reading into the research on it. If I find credible research suggesting that people in the Neolithic were as dumb as the rocks they used to build things, I promise I will report back. After all, science is about following the evidence, and this newsletter is about following the science.

But starting with this assumption is important. Because: what happens when you value-judge something, when you say “people in history were morons”, or even “people today are morons compared with history”? Well, you rank them. You say “this is better than that” - and in doing so, you put one in a category of being less interesting than the other. This stops curiosity dead. It just kills it. But if you assume people exist on a level playing-field of interestingness, it’s much easier to get curious about what you don’t yet know about them, including their seemingly “weird” behaviour.

So really, this is about the way we treat difference. Different ideas, different technologies, different beliefs, every difference under the sun. Instead of immediately ranking difference (which is a curiosity-killer), we can respect it. Or at least try to. Value judgements are so deeply hammered into us that this is phenomenally hard. Just read, I dunno, someone’s Substack about music. But we can try, because ultimately it will help us understand difference better.

And one way we can do this is by assuming that people in history weren’t any stupider than we are.

Of course, this opens a can of worms the size of the former British Empire, and in doing so, makes a mockery of a lot of gruesomely xenophobic ideas. Oh really, so every collection of human beings is more or less the same, then? What does that mean for historical ideas of land ownership and property? (You should go read Antonia Malchik’s Substack on this.)

What does that make those so-called civilized people doing the so-called civilizing back then?

What does that mean for arguments like “oh yes, the Parthenon Sculptures are being held by the British Museum and not returned to Greece because historically, the Greeks haven’t shown they can’t look after them, and anyway, far more people visit the British Museum and isn’t it really about educating the world? Hm?”

There are many arguments going on around these things. And, you know, there should be. But while the facts are being dug up and thrashed out and fact-checked down to the atomic level (because this seems a pretty terrible area of knowledge to get stuff wrong), we can at least start with a bunch of assumptions that will keep our minds as open as possible…

And who knows what that’ll help us dig up along the way?

Images: Laurenz Kleinheider; Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project; Luke Irwin.

There is so much here, and the idea of sonder with our ancestors (prehistoric and otherwise) is both beautiful and useful.

One of the first things I thought about as I read this, though, was the subconscious influence of old black-and-white photos (b&w photo = b&w life, right?). Just as people in the past were generally as intelligent as us, their world was also just as colorful. Now I'm wondering what other similar things are distorting my impressions of the past

Sonder is my new favorite word. Also “mapping the relationships between things” is such a perfect line for what you do here and what curiosity does for us in general. If we can’t see the relationships and connections between things, we’ve lost something for sure. Thanks for a wonderful read (and the shout out!)