Europe's Lost World (And The Megaflood That Ended It)

The ultimate Trip To The Seaside Where Everything Went Wrong.

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, science and joyful, friendly stupidity…

Continuing this season’s theme of looking at our planet’s defining characteristic, today’s newsletter answers the hair-raising question “hey, so, that Zanclean Megaflood thing from 6 million years ago that you recently wrote about: I know there were no people back then, but - what if there were? What would it have done to them?”

Alarmingly, I don’t have to look very far in time and space for an answer to this - just a few hundred miles & back a few thousand years, to a day when the North Sea unleashed thousands of years of climate change upon Europe, all in one go.

(Fellow Brits: this may permanently ruin all your trips to the seaside. Sorry.)

Between May and August 1897, the British magazine The Idler published a three-part science fiction story from up & coming writer HG Wells.

The editors must have been delighted. Wells’s novel The Island Of Doctor Moreau had just launched the author’s career to great acclaim the previous year, showing him to be a speculative entertainer with a talent for asking uncomfortable moral & ethical questions. His next work, The Invisible Man, had only just been published (both as a novel and a serial in Pearson’s Weekly) - and in 1898 he’d release the work he’s now best-known for, The War Of The Worlds.

But what of this serialised novella, A Story Of The Stone Age, which reads like a brisker, more clipped version of Jean Auel’s The Clan Of The Cave Bear?

It starts like this:

“This story is of a time beyond the memory of man, before the beginning of history, a time when one might have walked dryshod from France (as we call it now) to England, and when a broad and sluggish Thames flowed through its marshes to meet its father Rhine, flowing through a wide and level country that is under water in these latter days, and which we know by the name of the North Sea….

On the lower slopes of the range, below the grassy spaces where the wild horses grazed, were forests of yew and sweet-chestnut and elm, and the thickets and dark places hid the grizzly bear and the hyæna, and the grey apes clambered through the branches. And still lower amidst the woodland and marsh and open grass along the Wey did this little drama play itself out to the end that I have to tell. Fifty thousand years ago it was, fifty thousand years—if the reckoning of geologists is correct.”

Have you read it? Have you even heard of it? I’d say the answer for almost everyone is a double-nope - and there’s a bleak irony here. Wells would be criticised for taking wild liberties with the real-world science in his work, particularly with Moreau (which seems unfair in retrospect, considering the science-as-magic excesses of, say, Star Trek and Star Wars)...

But with his largely forgotten A Story Of The Stone Age, Wells was more or less bang on the money.

One day in September 1931, a few dozen miles off England’s Norfolk coast, a stray lump of peat dredged up from the sea floor hits the deck of the trawler Colinda - and makes entirely the wrong sound.

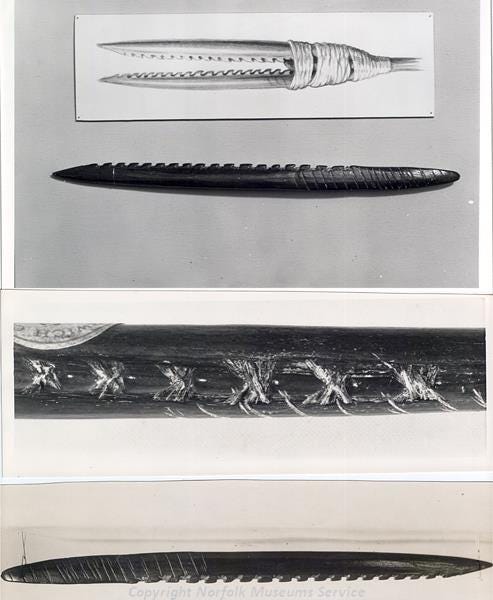

When the peat is pulled apart, the crew find one half of a ‘Maglemose’ harpoon, probably dating to the start of the British Mesolithic (“Middle Stone Age”), 12,000 to 10,000 years ago. Similar harpoons have been discovered along the Holderness (East Yorkshire) coast, tumbling out of the clay along the cliff edge. But what was it doing all the way out here?

Unfortunately, no samples were taken of the peat the harpoon was embedded in - but further clods dredged up by the same trawler revealed pollen from a mixed woodland environment. At some point, the floor of the North Sea was land, long enough for forests to spring up and peat to form in their wake…and people lived down there.

For anyone familiar with modern Britain, all this requires a pretty radical perspective shift - so, let’s have a go.

This is the island now called Great Britain, made up of the countries of England, Scotland and Wales, and part of the country-of-countries called (not entirely accurately) the United Kingdom.

I know I’m biased, but it’s a lovely place, and I recommend it to you heartily. The scenery is terrific, the weather is tolerable to fair, and barring a certain number of self-important & historically illiterate dimwits who refuse to accept the British Empire is a thing of the past, the people are absolutely lovely.

Here’s what happens to that picture if climate change continues unchecked for the next few hundred years, making the sea rise by 5 metres:

(Map courtesy of My Flood Map, which uses data from NASA.)

(UPDATE: there’s actually a big question mark about how accurate the above flood map really is to the east of this image - I suspected as such after more recently reading predictions for how The Netherlands is tackling sea level rises, and see the correction from Carlos in the comments below. I’ll return and update this properly after doing some research and fact-checking. In the meantime: take it with a huge pinch of sea-salt.)

At first glance, Britain’s got off pretty lightly. Sure, the land north of Peterborough is a colossal swamp, and my childhood home of East Yorkshire has become more or less an island, but - mostly salvageable?

This is because Britain is mainly upland terrain. (Think of all those scenic cliffs adorning British tourism campaigns.) For a better idea of what’s really hitting humanity by this point, look east to where the Netherlands used to be.

It’s not the first time Europe has faced flooding like this. Until 100,000 years ago, what we now call Northern Europe was locked under deep sheets of ice, as it had been for about 2.4 million years. Much of the world’s seawater, locked up in vast glaciers.

(I know, I know - there’s no way to imagine these things, but this is why we invented numbers, so let’s use them until things get a bit more manageable in the brainpan area.)

The most recent of these “lesser-extent” periods is an interglacial which we now called the Holocene, where we first make an appearance. It started 25,000 years ago. That’s about a thousand generations of humans (of which we know something of the last twenty, a little of perhaps the next hundred and basically nothing about the rest).

In 1988, the harpoon retrieved by the Colinda was radiocarbon dated to 11,740 years ago (± 150 years), more or less smack in the middle of that great thawing period. And the peat it was lodged in was 20 fathoms deep - about 120 feet, or 36 metres.

So, presuming that artefact was more or less in the place where it was dropped by human hands, that’s seven times deeper than the amount of sea that would drown most of the modern Netherlands.

(And that amount of water is a conservative estimate: recent studies estimate the sea-level around 18,000 years ago was nearly four times lower than that, at 120 metres below the level of today’s North Sea.)

Let’s say that seawater was somehow sucked up (or was miraculously locked back into the icecaps). How much of the modern seabed would it expose?

Answer: enough of it to create continuous land from Great Britain to Norway.

This astonishing map is from the Lost Frontiers initiative, a project of the University of Bradford. Except, “project” doesn’t really convey what they’re attempting here. It’s currently the largest prehistoric archaeological investigation in the world:

“To date nearly 43,000km2 of prehistoric countryside, with its rivers, streams, lakes, hills, has been mapped and clothed within computer models to show how the landscape and people reacted to massive climate change.”

- Professor Vince Gaffney, Project Principal Investigator

The name of this vanished expanse is Doggerland, named after the now-underwater Dogger sandbank 60 miles off the current English coast, which must have once formed a line of ancient hills along its eastern horizon.

I’ve been talking about water draining away, so it’s easy to look at this map and imagine something like a beach at low tide: lots of mud, everything damp and treacherous. Instead, think of something like this:

(Close enough, anyway.)

Mesolithic humans were what we now call hunter-gatherers: a sweeping term that can lead to confusion, especially considering the range of behaviour over truly enormous tracts of time and space that it’s applied to.

It seems highly likely that most Mesolithic people were only semi-nomadic: they moved around for part of the year, chasing the food as it waxed & waned with the seasons, and the rest of the time they stopped in settlements built near reliable sources of food & water.

The case study for this is Star Carr in North Yorkshire, Britain’s best-known Mesolithic site and home to its oldest structure:

“As well as its natural beauty, its shelter and its resources, there was perhaps a special magic to the place, as indicated by the deposition of the red deer antlers. In this respect, Star Carr is important because it hints at the mindset of an early Mesolithic lake dweller, suggesting an emotional and spiritual attachment to a particular place, as distinct from a simple desire to exploit its resources and move on.”

- Chris Catling, Archaeology.co.uk

By the time they were starting to populate Doggerland, Mesolthic people were learning to build permanent homes - even if they were only occupying them for parts of the year. If Star Carr’s eight-century history as a settlement is typical, these weren’t temporary things. Generations of families lived and died here. And why not? Life here must have been good (by Mesolithic standards).

Except - remember these are the uplands. Generally speaking, the higher you get, the thinner the natural resources. If people at this time were building seasonal outposts near sources of food and water, they’re much more likely to have been doing so on terrain nearer sea level, especially along the coast. In other words: they’d have much preferred the rich pickings of Doggerland to the bleaker fare of North Yorkshire.

How many people? Incredibly hard to say, considering the current evidence. Recent estimates of populations in southern Scandinavia only number in the hundreds. Just a few thousand across the whole of Doggerland? It seems possible.

However many there were, it must have been a paradise compared to the higher terrain elsewhere. Doggerland offered year-round food from the coast, food from rivers, from deer, wild boar, berries, birds, otters, beavers. I mean, sure, the sea seemed to be creeping inland a bit more ever year, but hey - that'd be a problem for future generations to sort out.

As the sea steadily advanced, the population adjusted, retreating above each newly-established shoreline - and generation after generation, across thousands of years, Doggerland was nibbled away by the rising North Sea.

Did its inhabitants have stories about times when life was easier? How much were they aware that the world was changing under their feet? After all, we’re talking about a length of time much greater than the one currently separating us from Classical Greece - so it’s not hard to imagine those people keeping calm, carrying on and pretending nothing was much amiss, as humans tend to do.

But if the geological evidence is to be believed, there certainly wasn’t any ignoring what happened next.

Researchers don’t have a precise date for it, but on a day sometime between 6225 and 6170 BC, the world ended.

By this date, Doggerland was mostly reclaimed by the sea. The Dogger Bank had probably become a huge island, and since there’s no evidence that Mesolithic people were seafarers, who knows if there were people living there? But there must have still been settlements in the remaining lowlands to the south, where a shrinking land-bridge still connected Britain to France - and there must have been seasonally nomadic communities living along every stretch of coastline.

Perhaps it was the weight of a build-up of sediment from melting glaciers, reaching a tipping-point. Perhaps a massive earthquake struck Scandinavia. Perhaps a perfectly unfortunate storm of catastrophes happened, one triggering the other…

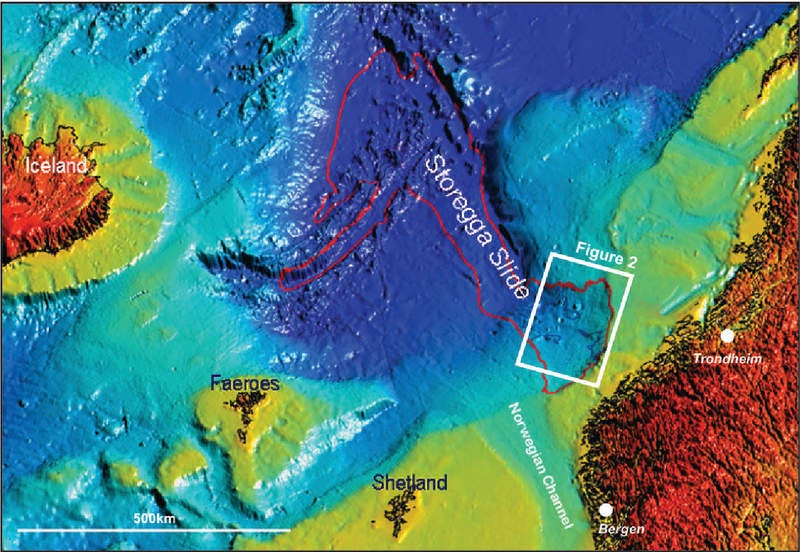

Off the shoreline of modern Norway, and hundreds of metres beneath the waves, the continental shelf collapsed.

The scale of the landslide this triggered is…yet another of those “oh come on, these are just numbers” situations, so I’ll try a few comparisons.

Perhaps you know about the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, source of the loudest noise in human history (it circled the globe seven times). That explosion blasted so much rock, ash and debris into the atmosphere that triggered a volcanic winter in the Northern Hemisphere and darkened the skies worldwide for years afterwards…

How much rock, debris etc? About six cubic miles of the stuff.

In comparison, the Mesolithic Storegga event (Old Norse for “Great Edge”) saw the collapse of an 180-mile-wide stretch of shelf in a gargantuan underwater torrent of rock and earth that slid nearly a thousand miles, into the Norwegian Sea’s abyssal plain. That’s an estimated 840 cubic miles of shelf material on the move - transferring an unimaginably vast pulse of kinetic energy into all the seawater it thrust aside.

You’ve seen disaster movies. You know what happens next.

The subsequent tsunamis that raced in all directions would have been astounding. When they thundered into the shallows of Doggerland, they’d be anything up to 25 metres tall.

Here’s a modern 25-metre wave for comparison.

Now imagine a whole sea made of waves like that, hitting the coastline you’re currently running away from in mortal terror - and then roaring up to 20 miles inland.

(Imagine not even understanding what was happening.)

Some Mesolithic people must have had a chance. Certainly the ones in the uplands of now-Britain, now-France and so on. But the rest? It’s difficult to imagine. Even if they survived the initial tsunamis and braved the chaos of the floodwaters until they finally receded (I haven’t seen anything to indicate how long this would have taken, but photos like this suggest it wasn’t quick) - well, their entire way of life had been extinguished. Every settlement and every reliable source of food had been destroyed. A whole world had died - in one day.

Clearly if all this happened as the evidence currently suggests, there were some survivors - it’s ultimately why I’m writing this. But the rest is mostly a matter of speculation at this point. What’s needed is a lot more archaeological research - and that is becoming a race against time right now, as the North Sea fills up with windfarms:

For Gaffney and colleagues, the rapid development of offshore wind power presents an incredible opportunity – and a concern. “We’re now in the perfect position to explore these areas and extract sediment cores, but we need the funding to do it fast as the opportunity to pursue such research will effectively disappear over very large areas of the seabed, effectively forever, if action is not taken in advance of windfarm development,” he says.

As Professor Gaffney says, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s certainly encouraging news for future electricity generation (the world just hit the 10% mark from wind & solar), and the nightmare in Ukraine is showing why it’s a good thing for the countries of the world to be able to wean themselves off fossil fuels supplied by (and funding) violent dictatorships…

But it might also be good for research into Doggerland. A case in point: 15 years ago, a gift of a “small” dataset from an oilfield service company called Petroleum Geo-Services created a map of 2,300 square miles of the remnants of Doggerland - the biggest geophysical survey ever made available to archaeologists.

What other collaborations are possible?

For now, Doggerland remains, in essence, the biggest (and wettest) archaeological dig in the world, with so much to teach us about our past, and maybe even something about our future as well. Let’s hope those turbine cables don’t make too much of a mess down there.

Further Reading

“Mapping A Vanished Landscape” - Jason Urbanus, Archaeology.org

“Discover how Doggerland links Britain, Europe and ‘the last Brexit’” - Professor Vince Gaffney, Big Issue

The lost medieval port of Ravenser Odd (Twitter thread from fellow Substacker Florence Of Northumbria)

Images: Raquel Pedrotti; Illiya Vjestica; Norfolk Heritage Explorer; Dominic Andrews / Archaeology.co.uk; Stozy10/Wikimedia; Aivars Vilks; Semantic Scholar.

The 'flood.firetree.net" link, My Flood Maps as you call them, is really horribly inaccurate. It uses ground-level measurements as its source for 'being under sea-level at x m SLR' which is just wrong. I live in the Netherlands. We have waterways, and as you know, we have dikes and sluizen, waterkeringen. And we have dedicated underwater-areas for when levels go beyond manageable. But that is not what that map shows, it makes it seem most of NW of NL would be drowned as soon as SLR goes to +1m. No it will not. In fact, most of NL is capable of handling +5m perfectly fine. In fact, this already occurs at certain rare storm strengths from the NW. Anyway, just telling you this, because it annoys me to no end that we constantly see this map being used as a source for a narrative that doesn't jive with reality.

I've found Doggerland fascinating figure a long time now. Have you read the Stephen Baxter historical fiction series set there? It starts with Stone Summer I believe.