The Blue Of Distance, Hope And - Mars?

Because some folk seem determined to believe *anything*.

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and toe-wiggling wonder. (And carrots.)

Since around half of you originally found me via Twitter - well, you may be wondering what on earth is happening over there right now. I know, right?

This is an excellent factual timeline (hat-tip the awesome Today In Tabs newsletter) but really, the following short video is as good a metaphor as anything I’ve seen:

So, really, who knows what’s next over there. Ye gawds.

Over here, though, we’re continuing with this season’s theme of colours and their meanings - and turning our gaze to the planet in our night sky with a visible reddish hue.

On the 20th July 1976, a little over 46 years ago, NASA’s Viking 1 lander touched down on the surface of Mars and started taking pictures.

It’s easy nowadays to forget that it wasn’t the first spacecraft to do this. It may sound like a plot twist from Apple TV’s For All Mankind, but the Soviet Union’s Mars 3 robotic probe was actually the first to attain a “soft landing” (ie. not crash), on December 2nd 1971.

(Alas that it only stayed operational for just under 2 minutes, and only sent back one featureless grey photo.)

This was the culmination of 11 years of the Soviets sending spacecraft towards Mars - a process where the first few didn’t reach Earth orbit, then a few did but couldn’t leave it, then a series of failures on the launch pad. At the same time, the United States was finding great success with its Mariner programme, and taking the first close-up photos of the surface of Mars.

So it was a surprise when the Soviets landed their probe. The Space Race suddenly looked far from over. But nowadays it’s Viking that everyone remembers - or at least many folk here in the West, and on the America-dominated Internet. It’s easy to say “the USA was first to land on Mars,” even though that isn’t true.

And perhaps some of it is down to what Viking 1 did the day after it landed.

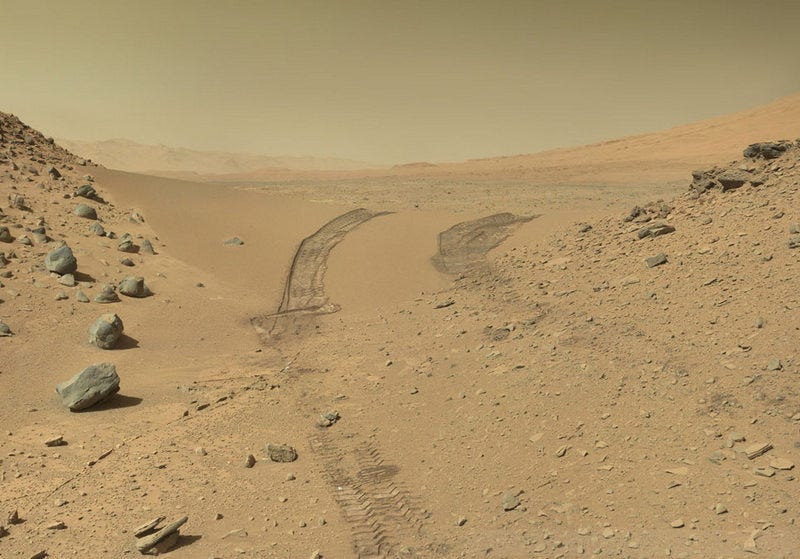

The above greyscale image is one of the great formative photos of my own childhood. I saw it in, I think, a copy of National Geographic Magazine (which I grew obsessed with), and I remember trying to tell my schoolfriends, “this is from another planet, isn’t that just craaaazy?”

It really is! You look at it, and you can imagine reaching out a hand and picking up some of those rocks. It’s a photograph that turns Mars from an abstract idea into a real place. (This is not pretend!)

But it’s nothing like the photo that was released by the Viking team the next day.

Wait, that’s Mars? Look at the sky! It looks just like here!

NASA’s official history of the event explains what happened:

“A lot of people would not forget that first color picture. Mutch [Thomas A. Mutch, lander imaging team leader] tells the tale as well as anyone.

During the first day following the early morning landing of Viking 1, his team was preoccupied with analysis and release of those first two images, "which, in quality and content, had greatly exceeded our expectations."

So much were they concentrating on the black and white pictures, that they were "dismally," to use Mutch's word, "unprepared to reconstruct and analyze the first color picture."

Mutch and his colleagues on the imaging team had been working long hours, along with everyone else, during the search for a landing site. Despite enthusiasm, people were tired. Many of the Viking scientists in the upcoming weeks would have to learn to present instant interpretations of their data for the press.

For the first color photograph, haste led to processing the Martian sky the wrong color.”

Isn’t it astonishing what adding a pale blue sky can do to how real Mars looks? It could be Morocco, or Egypt, or the Mojave. You could be feeling the hot sun on your back, the sand crunching and slithering under your feet, the hot smell of baked rock in your nostrils…

Colour is a powerful catalyst for the human imagination. The modern trend for colourising early black and white film is proof of this. Have a look at this colourised footage of English folk in 1901, utterly fascinated by the bizarre contraption that’s filming them (and letting us meet their eyes, here in the future). That’s a hundred and twenty years ago. And yet it can’t be, because - look how real it looks?

So the Viking 1 imaging team - exhausted after days of hard work and grinding stress - rendered the first colour image of Mars as if the light there behaves more or less the same way as it does here.

But it really doesn’t.

These kinds of comparative slip-ups are easy to make. Take that exciting scene at the beginning of the film version of The Martian, where the rocket is in danger of being blown over by a dust-storm. It’s absolutely thrilling to watch, and might actually look something like that - but the Martian atmosphere isn't thick enough to send you flying (around 6.5 millibars, vs the Earth's 1013.25 millibars at sea level - the same pressure as the air 22 miles above our heads in the Earth’s stratosphere). There’s just not enough ooomph. A gale-force wind would only feel like a moderate breeze.

(The real danger here, as I wrote about last year, is all that dust gunking up your tech and killing your ability to suck up solar energy.)

Thinking the Martian palette is comparable to Earth’s is another understandable slip-up. We were born to think that way, to correct towards it, and thinking otherwise takes effort.

Here’s the real sky of Mars, as you’d see it through the visor of your fancy heated spacesuit Mars-suit:

The reason that skies get that kind of opaque wash of colour - mostly blue on Earth, mostly this vaguely sickly orange/butterscotch colour on Mars - is due to the optical process called scattering.

In my reading circle on Threadable, we’ve been looking at my favourite chapter of Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide To Getting Lost (2005), where she describes the blue of the sky as “lost light”. It might sound highfalutin and super-poetical, but it’s actually a beautiful way to describe the real science at work:

(If you want to join us for free, click here - only iOS/Mac for now - or read more about how it works in this newsletter.)

Scattering also explains why our sunsets are red: at that angle, the light has passed through so much atmosphere that all the blue has been scattered out, leaving wavelengths towards the red end of the spectrum.

But on Mars the rules are different. The weak Martian air (95% carbon dioxide, 2.8% molecular nitrogen, a wee pinch of argon) contains a lot of dust particles which are a lot closer in size to the wavelengths of visible light. This leads to a different form of scattering, called Mie, where longer wavelengths (redder ones) tend to scatter equally in all directions, while shorter wavelengths (the blues) scatter at slighter angles. (This effect also happens here on Earth, but it’s swamped by the far more common Rayleigh scattering).

The result is that on Mars, the daytime sky is flooded with ‘lost’ red light. But - what about sunsets? Would the reverse be true?

Ohhhhh yes indeed it would:

What does a blue like this do to us? (Hey, how do you feel, looking at that photo?)

This may seem like a squishily unscientific question. But I think it cuts to the heart of why that first incorrectly colour-balanced photo from Mars refuses to go away.

Because - you guessed it - it’s now a conspiracy theory. 🥳🎉🤦♂️

It seems there are folk absolutely convinced that NASA has been covering things up the whole time, and Mars is in truth a place of tranquil blue skies, pleasant temperatures and more than enough land for the wretched offspring of all the Evil Corporate Elites who have burrowed into the world’s space agencies like worms into fallen apples - and any moment now, The Truth is going to come out at last!

(I’m not linking to any of the websites making these claims, nor to the tabloid newspapers gleefully amplifying them to grub for clicks. Nuts to that stuff.)

Why do folk latch onto such things? This is the subject of much research right now, primarily for democracy-defending reasons - but here, perhaps part of it is a fundamental misunderstanding of how errors work in science.

Of course ‘mistakes’ (incorrect assumptions & models as well as outright cock-ups) happen. That’s the scientific process at work, or, occasionally, the human limits of trying to apply it under enormous pressure. Good science is testing hypotheses and finding many of them to be wide of reality. This usually means you have learned something valuable, so you correct for it and move onwards.

This should be a truism for everyday life as well (“if you’re always right, you’re probably an idiot”) but somehow, when it’s conspiracy theories aimed at research, any correction turns into a Gotcha! indicator that those feckless experts were lying from the start. Absolutely exasperating.

Yet in the case of a blue sky on Mars, maybe it’s a little easier to explain. Blue skies mean something profound to us. Something beyond optics or physics or numbers, sometimes even beyond words. They lift our spirits in deeply-felt but poorly-understood ways. They inject a little faith into the day that wasn’t there before. They say, “hey, quick reminder: where there’s life, there’s hope.”

And there’s also how things look when they’re far away from us, here on Earth.

That faded, scattered blue between you and those distant mountains that makes them look so oddly appealing, stirring up a wistful longing to be there, like when you see a bird hanging in the sky and think Ah, to have THAT freedom…

Yet this blueness doesn’t exist. Not on the ground, anyway. It’s about as real as a rainbow:

But maybe experiencing this ‘blue of distance’ can teach us something about sitting with our longings instead of immediately trying to extinguish them:

(This is, after all, the essence of curiosity itself: a thirst to know something that can motivate you onwards in an excitingly purposeful way. So why be so quick to “solve” your curiosity and move onto other things, when it can be such a bottomless source of personal wellbeing?)

So: if conspiracy theorists are freaking out now about the lack of blue skies on Mars, what will psychologists of the future have to deal with - for example, on a Martian colony, where every day looks subtly “wrong” and it’s only at sunset that we glimpse the colour we associate with warmth, life and hope? Or will we adjust a lot better than that, perhaps because of the way a good Earth sunset makes us feel?

A little later on that July day in 1976, James A. Pollack of the Viking imaging team released a new, corrected version of that first colour image - to a chorus of amiable boos and hisses from the press.

But a day later, astronomer Carl Sagan (who had chosen the landing site for Viking 1) poked a little fun at this:

"The sort of boos given to Jerry Pollack's pronouncement about a pink sky reflects our wish for Mars to be just like the Earth."

As much as we love the colours of our home-world (and should maybe work a bit harder to keep them fresh and bright), the wider universe outside our front door is a whole new range of colour schemes, with new (and sometimes wildly counterintuitive) meanings to attach to every part of them…

Let’s hope our imaginations are up to the job.

Images: Wikimedia/Roel van der Hoorn (Van der Hoorn); solarsystem.nasa.gov; Threadable; NASA, JPL-Caltech, MSSS.

Part of me wonders if the skies of Mars wouldn't slowly drive human's insane. The year before we left Seattle was the first of the major wildfires that have plagued the PNW of recent years. And for days we had this yellowish haze hanging over the city, making it feel positively post-apocalyptic. You could just feel the "wrongness" of it getting under your sky, that color always sitting there reminding you all was not right with the world. I loathed that feeling.

I wonder if the Mars blue sky conspiracy theory is contributing to Elon Musk's desire to colonize Mars...