Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity, attention, wonder and, every now and again, horrifyingly gargantuan ancient floods. (If you don’t yet know that story, please sit down before you click through - it’s on a scale that can make you dizzy thinking about it.)

First, a few science-related updates:

1. Staying with this season’s theme of colour, here are two frogs, both of the same species (Hyla orientalis):

The difference? The one on the right has its normal bright green skin colour. The one on the left was living near Chernobyl.

As this Phys.Org article explains (hat-tip to my friend Andre), a three-year study of dorsal skin colour of tree frogs in the Chernobyl area in the wake of the 1986 accident found the radiation emitted by the damaged nuclear plant seems to have triggered an evolutionary response, favouring the survival of frogs with more melanin tinting their skin (melanin helps protects living creatures against radiation of all kinds).

If so, this has happened in just a little over ten generations of frogs. That’s mind-bogglingly fast. (In human terms, that’d be around 250-300 years!) Whew. There’s clearly so much more to learn about how fast biology can pivot in the face of an environmental crisis - and now seems a good time to be learning it?

2. Following on from last week’s newsletter about how the classical world was often splashed with paint (sometimes hideously, to modern eyes), here’s a perfect example from Egypt! Sam Childress of The Cairo Dispatch left a comment to say she was currently wandering round the still-painted ruins of Luxor - and now you can see it for yourself in her newsletter here. (Thanks, Sam.)

3. Justice for goldfish everywhere! As I explained in this newsletter from September last year, it’s an urban myth (and the source of many poorly fact-checked memes) that goldfish have unusually terrible memories & attention spans - and here, at last, is some high-profile research to hammer it home.

But not only do they have respectable memories, they also appear to process distances in a surprisingly weird way:

“According to the researchers, the results indicate that goldfish estimate distances by looking for the apparent motion of patterns in their environment, called optic flow.

They said many terrestrial species are known to use optic flow to estimate distance, but goldfish appear to process the information differently.

Terrestrial animals, including humans and honey bees, estimate distances by measuring how the angle between their eye and surrounding objects changes as they travel.

Goldfish appear to use the number of contrast changes experienced en-route, the researchers said.”

So not only do goldfish remember everything around them, it also seems they see and measure the world very differently to the way we do.

(Hey, maybe we’d learn a lot from goldfish, if we weren’t so busy insulting them?)

Okay. So today, I’d like to return to one of the most fun things I’ve done through this newsletter to date, to give it a second proper go.

I hope you’re up for that?

There are, truth be told, at least two things wrong with this newsletter on the average day of the week.

Firstly, it’s a passive experience for you: here’s me, broadcasting away like I’m important or something, with the apparent presumption that I know more than you about what I’m writing about (since so many of you are educators, scientists and the like, this is a foolish think to assume) - and secondly, because of the one-way format of this thing, I’m not giving you much of an opportunity to add the brilliance of your own ideas to the conversation, and therefore not learning anywhere near as much as I could be.

Fact is, I am often as much a student on the subject matters of these newsletters as you are. Hugely more so, in some cases! (There are now some devastatingly qualified people reading Everything Is Amazing, as a small, terrified voice in my head likes to remind me late at night.)

And - well, that’s ridiculous. If we were chatting in the pub, I’d probably have shut up long before now, so I can hear what you have to say.

For this reason, back at the start of season 4 I tried a fun experiment to correct both of these issues, by using a terrific new social reading app called Threadable, which allows us to all read through a text together. It also allows you to leave your own notes, including the type that everyone else can read - a bit like scribbling in the margins of a book, but without the mess and with all the extra sideways-linking cleverness of the Web brought to bear…

It was a delight to use. The experiment was a success!

(Only thing to bear in mind here: Threadable is currently only iOS/Mac only. You’ll need an iPad or iPhone running iOS 12.4 onwards, or macOS 11.0. To users of Android and Windows, I’m so sorry - but you’ll still be getting my writeups of each upcoming reading, in future newsletters.)

Honestly, why this kind of shared reading experience in an app isn’t already standard online behaviour (especially within academia) I’ll never known - but Threadable are doing it, and it’s really great to see.

It’s particularly great if, say, you write a science-based newsletter and you know a lot of your audience is madly knowledgeable on many of the topics you write about, and you’d love to get their perspective and learn from them as you go along, ideally before you ended up saying anything that’s embarrassingly incorrect. There - I said it.

Anyway, that first readthrough was back in February. Since then, the Threadable team have hugely improved the app, and they’ve asked me if I wanted to give it another go at running these mass-reading experiments, except this time on the subject of the science and philosophy of colour?

THAT’S A BIG YES.

As I said in my first piece on the work of Edmund Burke (the subject of that first reading circle), it’s sometimes just as valuable to read the early scientific writing that was wrong as reading the stuff that proved to be correct:

“Where do first principles come from? In every case, they’re…the product of human minds. Just another argument, suggested by the evidence but constructed by the brains of smart people, and always open to being tested to see if they hold up.

This is essential what good science is: a conclusion, backed up with repeatable evidence, so with enough time and effort you could retrace that thinker’s argument from first principles. Therein lies the thrill for confident, ambitious young students with no sense of proportion: what if I found a way to overturn a first principle, or something near it? What if I discovered a new branch of science and changed the world FOREVER?

Well, the only way that’s possible is to know how all the existing models are constructed - and to do that, you have to be able to retrace everyone’s steps, from the very beginning of modern science. You have to understand whole arguments from scratch, in as close to the original author’s words as possible, including with those theories that are so universally accepted that hardly any non-scientist gives them a second thought these days…

And to do all that, you need all those original ‘wrong’ science books.”

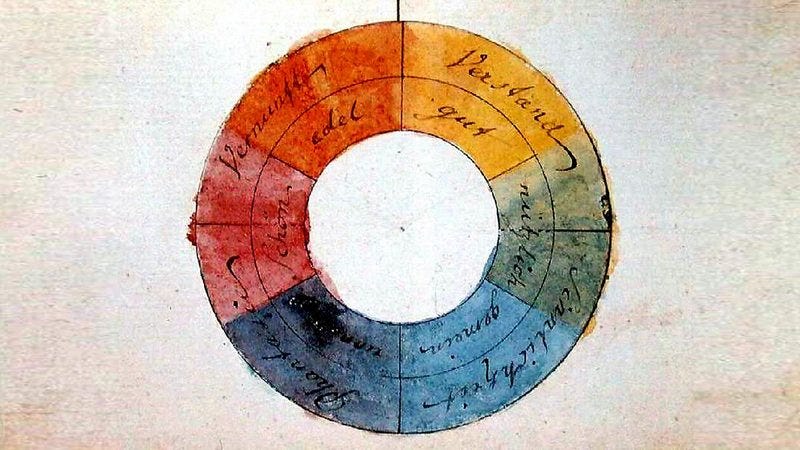

In this spirit, I’m about to work through the first part of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Theory Of Colours (1810) - a piece of work famous for being a noble failure in the field of describing the physical form and function of colour.

That’s “failure” because it doesn’t tally with the widely-accepted modern understand of optics first explored by Isaac Newton - and “noble” because the way Goethe was wrong was brilliant, imaginative and commendably experimental. It’s a masterclass in beautiful, stimulating ideas - and while Goethe wasn’t a scientist in the sense it’s understood nowadays (he was a poet, artist and politician), he had a lot to say that added to the conversation, if sometimes only to evoke replies of “um, I don’t believe that’s quite right, is it?”

At least, this is my understand of Goethe’s work. I don’t know this, because I haven’t read it yet. I’m going into this as cold as you - unless you’ve already read it, in which case, you should be the one writing this newsletter right now! (But don’t write in and ask for the keys to this publication. You can’t have them. I’m having too much fun.)

Would you like to join my Threadable reading circle on colours, starting tomorrow with Goethe?

If so, click > here < .

That link should take you to the Threadable app’s installation page, beyond which it should then usher you onwards into my Circle.

(And if it doesn’t? Sign into the app, go to “Home,” find “All Circles” and swipe sideways until you find “The Meaning Of Colours” with its multicoloured picture of a flower. Click through and request access. As soon as I see it, I’ll let you in - and you’re good to go.)

Hope to see you in there!

- Mike

Images: Possessed Photography; Open Culture; Phys.Org.

I’m *not* going to read Goethe (sorry), but if it goes well and you’re looking for another old text on color that is wacky but also weirdly prescient you could do Edgar Cayce’s color theory book, which is all about different colors stimulating different psychic states because of how they vibrate. He was kind of full of it and kind of not? Like that saffron color of Buddhist monks robes? Supposedly very high vibration according to old Edgar, and who knows? But I have been in rooms painted that color and the color is, for lack of a better term, activating. Enervating, maybe? Unless you hate orange in all its permutations, I guess. Wonder what old Edgar would have to say about those people?

Well I found your circle. I thought the circle was called something other than Geology