Why Classical Greece Looked Like Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory

And other horrifyingly colourful lessons from history.

Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and wonder - which you can get free in your Inbox, if you sign up below:

Today’s audio newsletter is read by the author in his rough, gravelly Yorkshire voice. Click below to get an earful (or scroll down for the transcript):

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello! This is Everything is Amazing, a newsletter about science and curiosity, awe and wonder, and how ridiculously interesting the world is, as well as just, you know, ridiculous.

This edition, which as you can hear I’m creating with the part of my face usually reserved for eating cake, is about colours - and so it may be a bit weird to be doing this, because, aren’t colours a visual thing, rather than an audio thing? Yes! Unless you have synaesthesia, which allows some people to experience sounds as colours, which I’ll talk about another time.

(Absolutely fascinating. I have a friend with synaesthesia, and she told me that when she hears the name “Mike Sowden”, she sees the colour brown. I’m sure that could be the beginning of a joke, so let’s move on.)

So this particular newsletter is about what colours mean. There are two ways to look at this:

what colours mean in a universal, scientifically rigorous sense, which is, as far as I can tell, is so immensely hard to determine that I could spend the next decade looking into it…

…and secondly what colours mean in the squishy, fickle, human-powered sense, the ideas ancient and modern that we’ve attached to colours, which is a much easier topic to look at, and because it’s all about humans and what’s in their heads, it doesn’t even have to make sense.

So, guess which type I’m going for today.

But before I do that: a disclaimer. There are now - *takes a breath* - 12,000 of you reading this. I honestly don’t know what’s even happening, but for both our sakes and for the sake of this newsletter, I’m going to pretend that I do. Hope that’s okay with you.

So - what’s your favourite colour?

No, seriously. I’m asking. What is it? Say it out loud, I’ll leave a pause. Ready? Your favourite colour is…

[………….........]

Okay. Really? THAT’S your favourite colour? Well, I’ll try not to judge, I’m sure you have your reasons.

But you probably don’t have your reasons. Not consciously anyway. Generally speaking, the colours we surround ourselves with - well, we just like them. It’s an unreasoned thing in most cases, a mostly unconscious preference. If you work in home decor, or the fashion industry, or at the Pantone Color Institute in New Jersey, you’ll know a lot about the unconscious messages that colours convey, but for most people (myself included), it’s a felt thing. I like this colour because, well, I just like it.

You could say that this is a triumph of subliminal advertising, and you wouldn’t be too far wrong. We regard clothes as cool because we’ve been subtly persuaded they are for decades - and that’s long enough for our fashion sense to change, so when we look at old photos of ourselves, it’s marvellous to see how horrible our clothes were back then. But they weren’t! They were sort of normal. Now you can’t understand what the hell you were thinking, but in the 80s you got away with it. (In my case, only just.)

Fashion is about wanting to look good and make a statement about what kind of person you are. But colours? That’s trickier.

Maybe the intensity of the colour says something, like, “I’m making an effort to brighten the world up today”, a statement of your individuality, as opposed to what you wear for a funeral. But the colour itself is mostly a matter of taste, where “taste” is a thing we don’t interrogate too much, it looks good, or it looks not-good, which we often label as “bad”, even though it really means “not my own version of good”.

As far as human history has gone, this seems an unusual state of affairs.

The symbolism traditionally attached to colour has got a bit jumbled up these days. In traffic lights, red means danger, but if that was universally true, no political party on earth would pick that colour for their branding. Green is often associated with health, nature and life, but it’s also the colour of the “I’m going to puke” emoji (🤢🤮) and of rotting things, and also a synonym of inexperienced and unsophisticated. Again, if that was universally true, nobody would want to be associated with that in a professional context.

As for the colours of the clothes we wear, they’re generally all over the place these days. Partly because all those colours are affordable. It’s never been cheaper to wear any colour you wish. What unbelievable freedom we have to look absolutely ghastly, and really, we shouldn’t take this for granted.

But this urge to daub everything in every colour of the rainbow isn’t a new one. We look at, say, the ancient temples of Greece, and we see the colour of the stone itself giving the whole thing a solemn and regal air that perhaps we’ve acquired from more modern architecture that borrowed that style from the Greeks….and that’s how these associations take root. But in many cases, it seems those statues and temples actually originally had pigment on them. They were painted.

There was cinnabar (red), ochre (a bricky red-brown colour), madder (a pinkish-red - more on madder shortly), orpiment, which is an arsenic sulfide (yikes) that gives a yellow colour, there’s also azurite, a blue-tinged carbonate of copper that goes green with age and becomes malachite, there’s egyptian blue, made from calcium, silicon and copper, which is the oldest synthetic pigment in history, there’s carbon for black, and there’s lead carbonate, also called lead white.

All these colours were being used, and they would have made these ancient pieces of classic architecture look to our eyes as garish as the outside of the average McDonalds.

No, seriously. There’s an example from the Greek island of Aegina: a statue of a Trojan archer, dating back 2,500 years, and excavated in 1811. The original is now in a museum in Munich, and it’s gorgeous, in that creamy pale stone colour you associate with ancient sculpture. But after careful examination, the faint traces of its original colours could be seen. So scientists made a replica.

And I kid you not: he’s wearing yoga pants.

Or at least - you know those multicoloured leggings with the diamond pattern that make you feel full of loads of bendy energy just by looking at them? He’s wearing those.

And the quiver for his arrows is patterned the same way.

And on top of all that, he’s wearing a canary-yellow tunic covered with pictures of cute animals.

It’s like the walls of Troy are being defended by Willy Wonka.

And this seems to have extended everywhere. If you walked through the Parthenon in Athens, it would have been, in the words of historian Natalie Haynes, “a riot of colour and glitzy decoration”. Wherever a statue depicted metal, that would be painted gold, or silver, you know, in the really shiny way. Newly cast bronze would have been treated to have the faint look of - how can I say this - brown moulded plastic.

Everything would have looked, by modern standards, appallingly cheap. Most of us used to the monochromatic grandeur of Westminster Abbey or the White House would be appalled. Horrified. It would look like the most wretched of parodies, utterly lacking in good taste. What were they thinking?

Well, they were thinking like us. We paint things, don’t we? Sometimes brightly! What’s wrong with a splash of colour here and there?

But it wasn’t just the Greeks. The Egyptians painted their temples - hence, Egyptian Blue as I mentioned earlier. And analysis of the world-famous marble statue of Augustus Caesar discovered in Italy in 1863 in the remains of the villa of his third wife, Livia Drusilla - well, you maybe have seen this statue [it’s at the top of this newsletter]. It’s perhaps the most famous symbol of ancient Rome in existence today: Augustus, dressed in an ornately-carved breastplate with a robe around his waist, lifting his arm to point at something in the distance, like he’s modelling underwear for a mail-order catalogue.

And of course he’s all one colour. The colour of marble. It’s a statue. What other colour would it be?

Well, there’s a replica in the town of Braga in Portugal. You can go see it if you like. It’s - kind of hideous! His flesh is painted pink, the robe is a deep red, his hair is a kind of mousy-brown, his breastplate is, yes, left marble-white but is filled with details etched out in red and bright blue.

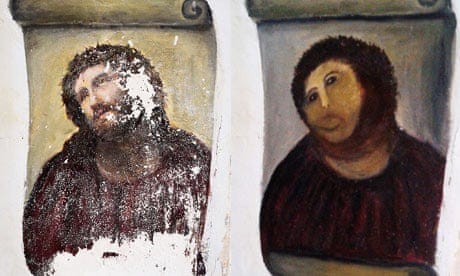

It’s almost as upsetting as the work of the well-meaning but artistically challenged Cecilia Giménez in Spain, who in 2012 noticed that a fresco of Jesus Christ at her local church was looking a bit worse for wear, so she decided to…freshen it up:

(I’m sure you’ve seen it. If you haven’t, I hope you have a stiff drink first.)

It seems the way ancient cultures used colours has very little, and quite often nothing, to do with what most of us think they looked like, and certainly nothing to do with what we generally expect sacred and socially important places to look like these days. It’s a monochromatic association we acquired simply because the paint got rubbed off. Think about that. Isn’t that bonkers?

So you shouldn’t be surprised to learn that working out the meaning of colour, let alone the use of it, for ancient societies from which we have basically no documentary evidence apart from a few scraps here and there - is really, really damn hard.

So let’s cheat, and look at more recent times.

My favourite colour, by the way, is blue. I’m obsessed with it - that special luminous blue you only seem to get in the Greek islands, the blue that mountains get when they’re far away, which Rebecca Solnit had some really interesting things to say about - more on that another time.

Blue blue blue.

(The only blues I’m not keen on are the variety where you sit on your porch with a guitar, mournfully complaining that sadness is your first name and your last name is misery, and you lost your woman and the rain is coming down and so on. Oh, and that song by Eiffel 65. Bloody awful. But all the other blues are fantastic.

And like any self-respecting ceruleaphile should (that’s “lover of blue things”), I got hold of a copy of Michel Pastoureau’s Blue: The History Of A Colour. Professor Pastoureau is an expert of medieval history and also of symbology, what things mean, and he’s working his way through the spectrum, having now also covered black, green, red and yellow in successive books.

But he started with blue, published by Princeton in 2001, and an absolutely gorgeous thing it is - and that’s how I know what happened in France around the turn of the 12th Century.

Now, at this time, if you wanted to look important, red was the way to go. Red, or white, or black. As a fashionable upstart intending to make your mark on society, you could say everything you wanted to say with these three colours - especially red, with its strong associations with the nobility and the throne.

But for some reason, around this time, the Virgin Mary brightened up her appearance. Until now she’d usually been depicted in darker colours: dark green, grey, brown and violet. Colours that suggested subdued emotions appropriate for mourning. But then she started being shown wearing blue, in brighter and brighter shades.

This led to two things: blue as a sign of prestige and divine power, and the king adopting blue as his regal colour - the latter obviously influenced by the former. And in the way of these things, this spread out into the nobility and in the symbolism it used. This can be seen in heraldry, the insignia from which you get the coats of arms used by wealthy, powerful individuals and their armies and so on.

Around 1200, the colour blue featured in around 5% of the coats of arms across Western Europe. By 1400, this had risen to 30% - so that’s from 1 in 20 to nearly a third of all of them.

This could also be seen in the way knights on horseback were depicted in the tales told about them.

Knights at this time were - well, analogies here could get a bit daft, National Geographic recently described them as “the superheroes of the medieval period” - or maybe the premier league footballers? I don’t know. Celebrities, anyway, except with none of the access that we have to celebs nowadays.

What they had were tales of these knights doing great deeds - and in the early 12th Century, a red knight was the baddie.

Red was a sign of corruption and evil.

Black was for mystery - not good or bad, just a big brooding question-mark on a horse.

White was unambiguously good - they’d have recognised Gandalf on Shadowfax for what he is.

Green meant insolent and inexperienced and foolish and probably designed to come to an end that serves as a moral warning to others.

And blue - well, blue meant nothing. There were no knights in those stories in blue, because it just didn’t signify anything.

But then blue knights started appearing. As the heroes. Blue knights, in their rich, almost glowingly blue armour, suddenly signified the height of purity, virtue and noble principle - and also, ability to hack people to bits.

So what triggered all this? What rewrote the meaning of blue in society?

A big factor seems to have been dyeing. Not the “what happens just after you’ve been hacked to bits” variety, but the type where cloth was dyed with colour. Until now, red had been most important - and red came mostly from the roots of a plant called madder, which still grows across Europe today. Madder cultivation was big business, and madder dyeing equally so.

At this time, all the major trades were arranged into powerful guilds, organisations that helped regulate commercial activities and protect their members against unfair competition - where unfair often meant “anyone who doesn’t abide by our rules”. These guilds were really powerful, and the cloth guilds were some with the most clout. The cloth dyers were the only ones allowed to dye, the weavers were the only ones who profited from all the weaving, and so on. Everyone had their place.

But then blue cloth started getting more and more desirable, made by creating a kind of paste called pastel from processing a herb called woad. Again woad’s now everywhere, and back then it had already been around for a long time - most famously used on the faces of the Iron Age inhabitants of now-Britain as they attacked the just-landed ships of Julius Caesar in 55 BC.

But now woad became big business - big enough that some weavers started bending the rules and doing a bit of woad-dyeing on the side to hurry the process along, so they could rake in as much profit as possible. So not only were there enormous fights between the madder cloth producers and the new blue-tinted upstarts, there were further fights between all the dyers and all the weavers, plus anyone else who was doing the woad-dyeing equivalent of brewing moonshine in their back yards. And then there was pollution: the nearby tanners needed clean water, so any dyers using streams upstream from them - well, more fighting. The whole period sounds like one great big barney.

But in some places the madder supporters went further, and went to the source of all their trouble in the first place. As Pastoureau notes:

“In Thuringia [modern day Turingen in central Germany] they went so far as to ask glass makers to depict blue devils in stained-glass windows as a way of discrediting the new fashion for blue. Father north, in Magdeburg, capital of the madder market for Germany and the Slavic countries, hell itself was painted blue in order to associate the rival colour with death and pain.”

Hm.

But after a few decades of this, and presumably an astronomical amount of brawling and underhand shenanigans, it was clear that blue wasn’t going away. Blue had won. And it stayed won: on the whole, red never regained its place it once had. So - the woad industry lived happily ever after?

Not quite!

A few hundred years later, other blue-tinting plants had been discovered, first in India and then across the Atlantic in the New World. On April 5th 1577, dyers from the city of London requested formal permission to use new plants from India to make the blue they called “indigo” - and suddenly, the woad industries across Europe were in exactly the same position that the madder crowd had been hundreds of years before.

In an attempt to protect some of them, Emperor Ferdinand III of Germany declared that indigo was “the devil’s colour” - and French dyers were threatened with death if they touched the stuff. All for naught, of course - eventually profit conquered all, and Europe’s woad industry was dug out by the roots.

As for blue clothing, what does it mean today?

Well, it’s still a sign of royalty, as in Royal Blue - but thanks to use of indigo to make blue jeans from 1873 onwards, it’s also the colour of the working man, of sensible boots and callused palms and a firm handshake. Who knows where blue will go next? (Perhaps it’ll become associated with me, and become the colour of idiocy. Who knows?)

But all this is a nice illustration of all the fluid, changing stories of human meaning tangled up in the colours we use. Including - your favourite colour.

Do you know any of those stories? Maybe you could go find them out. That might be fun?

So I’ll stop talking, and let you go do that.

Images: Wikimedia; Katya Shkiper; MedievalBritain.com/British Library; Till Niermann/Wikimedia.

My favorite color is green, shade depending on the day. Right now as I read this I am sitting in my very bright, sherbet-y green kitchen, which makes me quite happy. Particularly in the middle of the winter, when Upstate NY is generally grey and snowy and terribly depressing. It was also my favorite color when I was a kid, but then I switched to red for several decades. Can't say exactly why. I think it seemed more assertive and fiery, which were states I aspired to for any number of years.

An interesting story about indigo, which is that in the U.S. most of the indigo cultivation and dyeing was done by slaves. A famous Quaker abolitionist named John Woolman, in protest, refused to wear any indigo-dyed clothes and only dressed in undyed homespun for the rest of his adult life. Not unlike Ghandi many years later, though with a lot more layers since he lived in New Jersey.

My favourite thing to do is get very grumpy when medieval churches on TV are plain, whitewashed buildings. They would have been lavishly decorated within an inch of their life in a way modern people would find terribly gaudy. All the whitewashing and ransacking of ornament was done in the 16th century reformation when decoration was felt too ostentatious to be Christian. Protestantism probably had a huge influence on our aesthetics in a way we don’t consider!