The Fun Is Why

On quests and hobbies and 'pointless' things that can brighten up your life no end.

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about the science, wonder and weirdness of applied curiosity.

Today’s edition - on the subject of actually going out and doing stuff - even has an audio version below, read by yours truly!

So for both our sakes, let’s get this over with as quickly as possible.

TRANSCRIPT:

On March 1st of this year, Sarah Merker, a marketing executive from London, ate a scone.

If you don’t know what a scone is, allow me to light up your world forever: it’s an utterly delicious baked lump of wheat or oatmeal mixed with butter and sugar and baking powder, which rises when it’s cooked in the oven, but not too much, so it’s still somewhat dense and hefty - you know, I can easily imagine a thrown stale scone knocking someone off a bike.

And if you don’t know what a scone is because I’ve pronounced it wrong, what I mean is scone.

There are very few things that will genuinely cause an actual argument in Britain - even the question of whether the milk or the hot water go into a cup of tea first will usually generate little more than good-natured bickering, but for some reason, we’re all willing to fight over how you pronounce the word derived from the letters s, c, o, n and e, when employed verbally in that exact order.

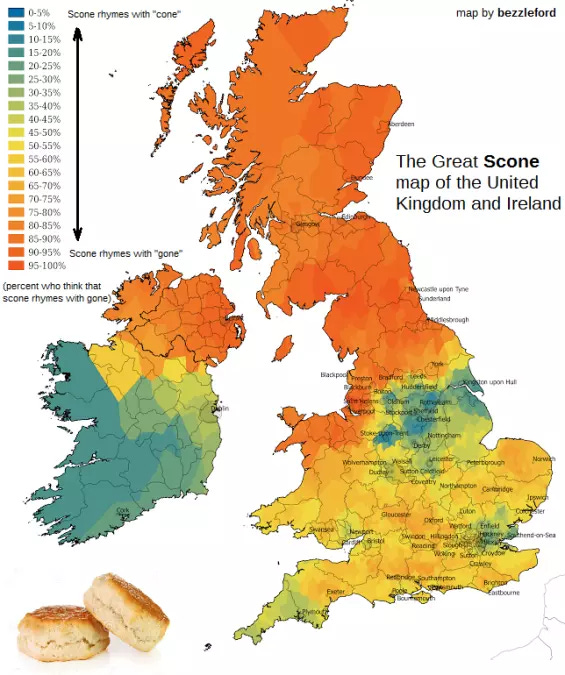

If you’re interested in the geographical breakdown, perhaps because you’re British and you want to know where your enemies are, a YouGov poll a decade ago showed a 51% bias towards scone [rhyming with “gone”], 42% preferring scone, and presumably the other 7% screaming oh for pity’s sake just stop this madness all of you, with their veins on their foreheads bulging.

As for regional breakdowns: us noble, salt of the earth Northerners prefer scones [rhyming with “gone”], as do our friends in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales - while the soft, corrupt Southerners with their irrational and foppishly Continental ways prefer scones [rhyming with “cone”].

Obviously it’s important for this newsletter that I don’t show any bias on this matter. And I certainly don’t want to cause any offence, because I’m a coward. So for the rest of this piece, I’ll refer to scones and scones interchangeably, which should hopefully upset everyone.

Sarah Merker, being from London, probably pronounces scones in a manner that some people would regard as monstrously incorrect. But nevertheless here she is, tucking into a scone. She’s in Northern Ireland, near the basalt columns of the Giant’s Causeway - and it’s taken her ten years to get here.

In August 2013, Sarah and her husband became members of the National Trust - the conservation charity that’s been looking after a lot of the stately homes, castles and famous landmarks across England, Wales and Northern Ireland for well over a century. Annual membership is around £70, which gets you free access to Britain’s more than 500 National Trust sites, and Sarah and her husband thought, “well, if we’re doing this, we’re going to get our money’s worth.”

So they started eating scones. One at every National Trust property that served food. All two hundred and forty four of them.

That’s why it’s taken ten years - and presumably thousands of pounds in membership fees, travel and accommodation - to complete this national baked goods treasure hunt.

But sadly, Sarah’s husband isn’t here. He died in 2018. Sarah chose this last property in his honour, because they’d previously visited it together.

“It didn’t even occur to me to give up, it gave me something to get out and about for,” she’ll later tell the Washington Post. “Everywhere I went, I was looking at it through his eyes.”

This is a heartwarming story. If you’re not feeling your heart warmed, I suggest checking your pulse. It’s lovely, if a little bittersweet. Everyone should be able to agree on this. And it should definitely make you want to eat a warm scone, right this second, heaped with clotted cream and fresh strawberry jam, maybe accompanied by a cup of Yorkshire tea. Again with the pulse thing.

But beyond this, opinions can quickly differ. Do you find this story inspiring? Does it make you think oooh, that sounds like a fun thing to do, I wish I’d done it? Or does it make you think - well, that’s nice, but it’s not exactly productive, is it? I mean, ten years! She could have written a book in that time, or started a business or changed the world or whatever.

We’ll return to this difference in a minute, but - well, actually, she did write a book. It’s called The National Trust Book of Scones: 50 delicious recipes and some curious crumbs of history, It came out in 2017, four years after they started sconning their way around the UK (no, that’s not a word), and it has nearly a thousand reviews on Amazon, so presumably it’s been selling steadily all this time. Great job.

And if you’re curious: their favourite of them all was the Christmas pudding scone topped with brandy butter in the Treasurer’s House in York, my old home. (I mean - York was my home, not - the Treasurer’s House.)

Anyway. Sarah’s ten year scone odyssey ended in March, and now she’s feeling at a bit of a loose end. She wants to keep yelling about the importance of scones, so she may try doing the National Trust properties here in Scotland, because it’s an entirely separate system. Or she may try a new challenge, as she’s grown interested in the difference between British scones and American biscuits, and she’s keen to start trying the latter. And I hear there are quite a few varieties, so this might take some time.

What Sarah found is the joy of being on a quest - and the great thing about quests is that they don’t have to make sense.

If you reacted to Sarah’s story with a shrug, and in the back of your mind a voice yelled but what was the point of it??!, then there’s something really interesting happening in your brain right now. You’ve heard a story of someone doing something for fun - really committing to it, in a way that takes a significant chunk of their life and a not inconsiderable amount of money - and you’ve tried to turn it into something it isn’t.

Because - what is the point? Will a quality-graded map of the National Trust’s scone output directly help anyone achieve their best life? Unlikely. Will it undo the economic ravages of political incompetence, or help rewild the UK, or usher in a golden future for humanity in general? Not directly, I suspect.

This is really about what I call the tyranny of usefulness: where the value of doing a thing, the “sense” bit of “it has to make sense”, goes back to two things.

Firstly, the old economic-based model of productivity that’s been haunting us since the industrial revolution - does it help me produce more widgets and therefore make more money and maybe help me retire a bit earlier? You know: “useful” stuff, not for “fun”.

And secondly: we can quantify the usefulness of it in advance. We’re doing it because we already know what we want to get out of it.

But here’s the thing. As I hope I’ve demonstrated over the last four and a bit seasons of this newsletter, there is great value in discovering things you never knew you didn’t know. It just feels great, and opens your mind in all sorts of ways - including so-called useful ones - to realise the world is filled with more interesting and even more joyful stuff than you ever could have guessed.

But it’s really hard to stumble across something you never knew existed. Hardest thing in the world. This is presumably part of why we’ve adopted all these behavioural traits we call “curiosity” - they help us get out of our normal lanes, just a bit, to help us adapt to changing conditions, or maybe just to be aware of them? Who knows.

But it seems that as well as giving us a lot of joy - that rush of endorphins from a good “wow!” that is always fun to experience and that is, let’s face it, my entire business model with this newsletter - as well as that, it seems that being curious and open to new ideas has all sorts of benefits, including emotional ones.

And if you’re happier and more hopeful, you have the stamina and the mental resilience to keep going - which is absolutely everything, in usefulness terms.

So way back in season 1 of Everything Is Amazing, I coined what absolutely nobody is calling Sowden’s First Law Of Curiosity, which is: “You just have to try lots of different stuff for no damn reason.”

And I reckon nothing quite fits that bill like a quest which, when you try to explain it to other people, sounds kind of stupid.

I feel very lucky that I come from a country that seems unusually obsessed with amateurism: you know, the dogged pursuit of an objectively useless pastime that you’re highly unlikely to ever get paid to do, perhaps wearing gear that an Olympic standard professional would see as instant career suicide. Really, this kind of committed amateurism can be found everywhere in the world, but the British are quite loud about theirs. We’re really proud of how we’re basically a bit crap at all this but we’re doing it anyway - and we have great fun in watching people’s expressions when we explain what they’re doing, and seeing them think But…but what’s the point? We live for those moments.

The useful word here is “hobby” - the thing that made a huge comeback during the pandemic lockdowns, when suddenly everyone seemed to discover how fun it was to just fart around doing not terribly useful things. A spiritual mass-rebellion against productivity, because if the world has gone completely mad, I might as well fulfill my lifelong dream of doing a full handstand, reading…uh, a book, learning to bake sourdough bread, or watching all 871 episodes of Doctor Who.

About the last one: well, you can’t. Sorry. Back when BBC TV shows were stored on rolls of film, sometimes the film was seen as more valuable than the stuff recorded on it, and so the BBC taped over at least nine episodes of Doctor Who. They’re gone.

(Or are they? Maybe you just discovered your quest for the next decade. Geronimo, Allons-y, off you pop and all that.)

The only requirement for a quest is that it’s fun. That’s its entire, self-contained reason for being. You can bolt other stuff onto the sides of it if you want, like Oooh, this would be a great way to discover if I could do this for a living, or I just want to do something madly different for a change that gets me out the house or I bought all these Doctor Who DVDs in a car boot sale for five quid so I can’t just throw them out, that would feel wrong.

Or maybe - and this is important - maybe you don’t know why.

Maybe you can’t justify it at all. I reckon that is the best-case scenario, because now it’s a total leap into the unknown, you don’t even know why this thing is calling to you so much, and you’re brave and smart enough to say, I don’t need to know right now, I just need to go find out.

But you probably want to have it make a bit of sense to you. Take writer Jacob Ready, who is trying to visit every bookstore in New York City because then he’d know where all the best books are: now you should now stop reading me, perhaps forever, because you’re going over to read Anne Kadet’s Substack newsletter about this story, and then every other edition of that newsletter because it’s a joy:

And Rob Walkerhas this gem on the value of a good quest:

Or maybe you want to learn to cook, so you pick up a copy of the legendary Larousse Gastronomique or something by Jamie Oliver, and vow to cook absolutely everything in it. (I have a friend who did that in her WordPress blog, it took her a year, and she absolutely loved the whole experience.)

Or you could do this entertainingly horrifying thing that Brendan Leonard did:

Or you could make every single salad in emily nunn’s newsletter - what an injection of raw joy into your diet that would be:

Or you could familiarise yourself with your surroundings by, say, visiting every bus-stop or Underground station - there are people who do this in London every year, and it’s even a Guinness World Record - the record is around 15 hours to visit every single station.

And that’s another thing: Guinness World Records, which are little more than legitimised excuses to go attempt some fairly useless and sometimes breathtakingly idiotic undertakings. Yes, it’s also about trying to become a minor celebrity, but it’s also just an excuse to have some fun doing a thing that you’d struggle to justify to yourself or anyone else in any other way. Like the world record for stacking M&Ms on top of each other. (Yes, this is a thing, I wrote about it here in 2021.)

So if you want to become more curious about the world around you but you’re not sure how, invent a quest for yourself. Give it a simple, easy to follow framework, like “make or visit all the x in y” or “achieve as much z by this date or with this much time”. Make it sufficiently dumb in both senses: in the sense that it’s a bit (or a lot) eccentric and really tricky to justify to strangers, and dumb in the sense that it’s always clear what you need to do next.

That’s it. Hopefully it’ll work as a fun engine for creating all sorts of experiences you never dreamed could happen to you. Or maybe it’ll be horrible! Who knows! Not me, that’s for sure, which is why nothing in this newsletter is legally binding in any way, don’t even try it.

But of course - there’s a line. And it’s always fun to peer over that line, at the people on the other side, in the hope that they’re that really special brand of lunatic that you can have great fun telling your friends about.

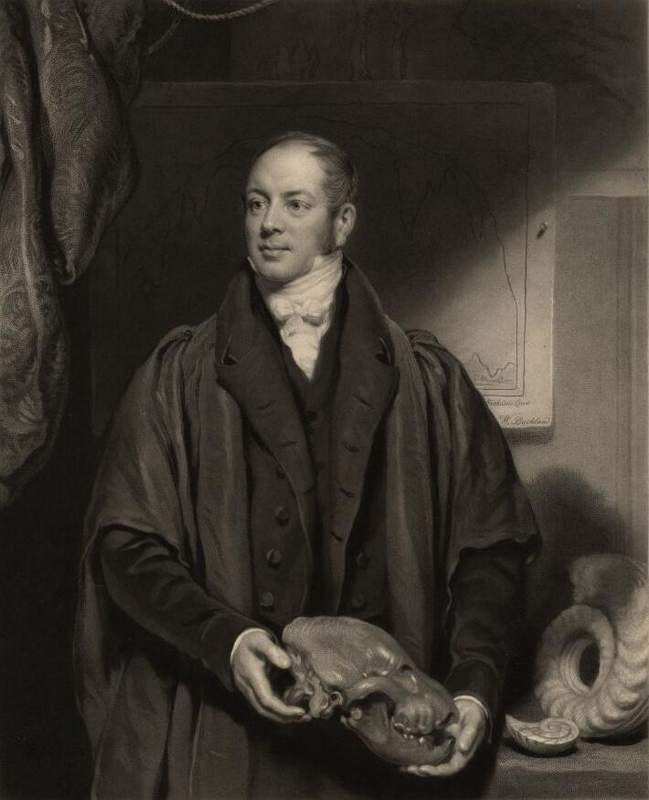

So we turn to The Very Reverend William Buckland, born 12th March 1784, died 14th August 1856, after a much-celebrated career as a theologian, geologist and paleontologist - and after spending most of his life trying to eat every living creature on Earth. Not by volume, but by variety. Just one or two of each of absolutely everything that ran, flew, scuttled, slithered, swam, buzzed or oozed through the natural world at that time.

Sounds horrifying! Is, indeed, horrifying! But these were Victorian times, where the term “naturalist” could mean a rather more invasive and aggressive form of investigating Nature, the kind where, for example, it regularly ends up on your plate.

As Fraser Lewry noted in The Guardian:

“No living creature was safe from Buckland's mania. Mice on toast were a regular feature of his no-doubt popular soirées, while other animals to guest at these events included the porpoise, puppy and panther ... and that's just the 'P's. Once, when visiting a cathedral, he was told of a local legend claiming that fresh saints' blood was to be found on the floor. Buckland, never one to turn down the opportunity to try a new flavour, licked the flagstones and was able to disprove the myth, immediately identifying the mystery liquid as bat urine.

Probably the most extraordinary of the great man's exploits came on a visit to Lord Harcourt, the Archbishop of York, at Nuneham Courtenay, just outside Oxford. Shown what was claimed to be the heart of Louis XVI, preserved in a silver casket (Harcourt was a collector of esoterica), Buckland immediately gobbled the fleshy artifact down, unable to resist the opportunity to chow down on the heart of a king.”

And if you’re looking for a more modern example to alarm you in much the same way, look no further than Michel Lotito, nicknamed “Monsieur Mangetout,” who spent the years 1978 to 1980 eating an entire Cessna light aircraft. I am not making this up.

So while I hope that the earlier part of this newsletter has given you a few ideas, I hope this part has given you exactly none, except that maybe that the point of hearing cautionary tales is that they help us avoid becoming one.

Thanks for listening.

- M

Images: BigThink/bezzleford; Sarah Kilian; Nadjib BR; Pexels/9143; Samuel Cousins/Wikimedia.

All of this heated sectarian debate between rhymes-with-cone and rhymes-with-gone and we haven’t even gotten into whether you put the jam on first or the clotted cream on first.

Will there ever be peace?

So maybe I didn't need to know Mr. Buckland was able to identify bat urine with one quick taste. 😝😝😝