Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and wonder, and the power of looking looking looking.

Today, we return to this season’s main focus: the unsurprisingly lively science of colours. We’ve already looked at newly invented ones, impossible ones, historical ones, changeable ones and the ones maybe only women can see.

So let’s consider the safest and most reassuring colour in the modern world - a colour that says Hey, everything’s great, trust me. It’s fiiiiine. I mean, what could possibly go wrong here?

What indeed? Let’s take an increasingly horrified look.

It’s 1775, and Swedish-German pharmaceutical chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele has made an astonishing discovery.

This is becoming something of a habit. Scheele is, by any measure, a brilliant scientist with an unquenchable curiosity and a thoroughly reckless fascination for his craft. This has meant a lot of experiments, bucketload of discoveries, and a short but supremely accomplished career that should have made him a household name (including now, hundreds of years later).

But alas. A kinder world might celebrate Scheele’s legacy for what it was. Instead, it affectionately ridicules it.

In one of his roundups of the history of science, the late sci fi author (and Professor of Biochemistry) Isaac Asimov called him “hard-luck Scheele". And in A Short History Of Nearly Everything, Bill Bryson has this to say:

“Scheele was both an extraordinary and an extraordinarily luckless fellow. A humble pharmacist with little in the way of advanced apparatus, he discovered eight elements - chlorine, fluorine, manganese, barium, molybdenum, tungsten, nitrogen and oxygen - and got credit for none of them. In every case, his finds were either overlooked or made it into publication after someone else had made the same discovery independently. He also discovered many useful compounds, among them ammonia, glycerin and tannic acid, and was the first to see the commercial potential of chlorine as a bleach - all breakthroughs that made other people extremely wealthy.”

But this new discovery in 1775 has the potential to turn the tide in Scheele’s favour.

To untrained eyes, it might not look like much - a solution of chemicals he’d somehow turned a pea-green colour by heating and stirring them together. But because of his line of work, Scheele knows that finding reliable and plentiful green dyes is a huge problem for so many industries (for example, the few natural-origin dyes that lend themselves to bulk production in the fashion industry tend to fade quickly under bright sunshine). He knows that the hunt is on for synthetical alternatives.

It’s also possible he’s still smarting from his previous colour-based discovery having failed to make an immediate splash, a bright-yellow hue that would later become known as Turner’s Patent Yellow - after the British manufacturer who stole the patent from him. Sigh.

Worse still, the previous year Scheele had discovered a gas that attacked many metals, worked as a bleaching agent, and when combined with soda it formed common salt (sodium chloride). Scheele had discovered chlorine - but thanks to misidentifying it at the time, it would be up to Humphrey Davy to later formally recognise the gas as an element and name it after the Greek word for its color, khloros (“greenish yellow”), thereby taking the credit.

This happened in 1810 - thirty-six years after Scheele’s discovery. Sucks to be you, Carl.

But now, perhaps, an opportunity. Could this rich, almost luminous green be of commercial use? And if so, could he bloody well be credited for discovering it, please?

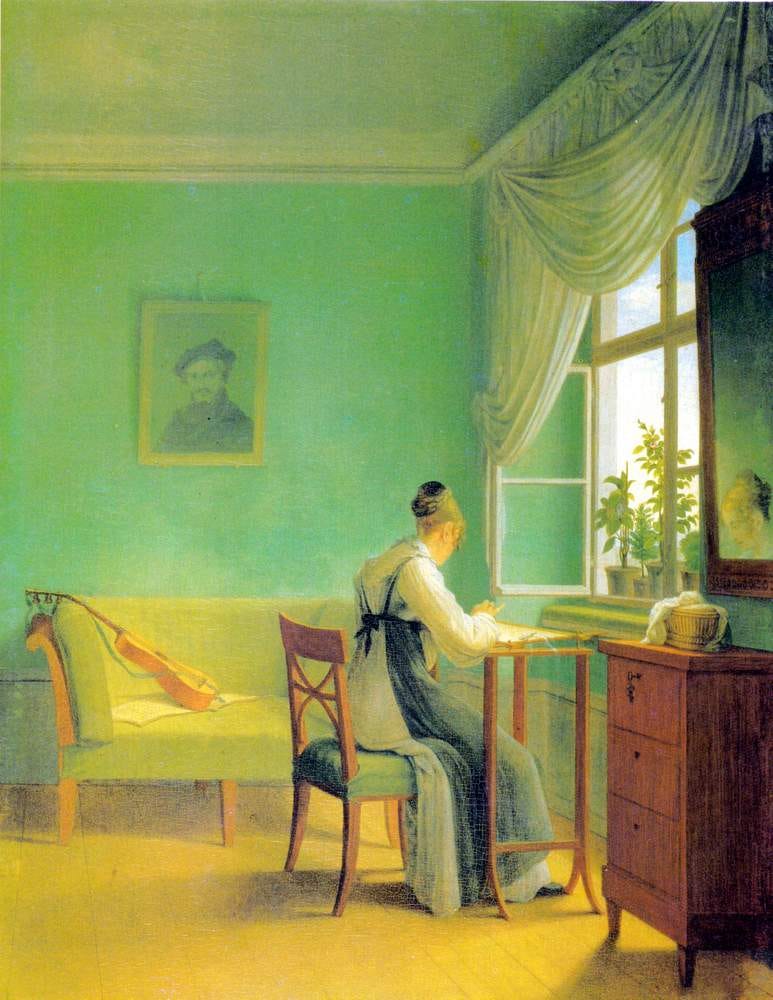

Behold the glory of Scheele’s Green, adorning the walls of the subject in Georg Friedrich Kersting’s Woman Embroidering (1812).

That’s probably wallpaper on the wall up there - a telling sign of how cheap the colour is to produce by this point. It’s singlehandedly triggered a small revolution in colour design. The Victorian world is obsessed with it - and rightly so, because, what other green so effortlessly mimics the verdant hues found in nature? A proper Goldilocks of a colour: not too much nor too little, neither drab nor a Day-Glo assault on the eyes, with no ugly tints or streaks bleeding through as it eventually fades.

It’s perfect for a post-Industrial-Revolution Britain (and France) that has grown disgruntled at how ugly its cities have become, how visually disconnected from the bright, Eden-like Utopian dreams in the high literature of the day.

The Victorian world is ready to turn everything this beautiful shade of green.

Like the Victorians, we’re increasingly obsessed with green things.

It’s not like green’s popularity ever went away, of course - even after the horror of….well, we’ll get to that in a minute. But according to various industry pundits, the colour green is currently extra-desirable: in home decor (“a recent survey by The Harris Poll found that online searches for “green paint” have more than doubled since 2020”) and in fashion, where Vogue confidently announced “wearing green is the closest you can come to taking a forest bath,” which, erm - no? But anyway: more people are wanting to wear green clothes is the point here.

Then there’s the other use of the word green, the vitally important one, the one where we take responsibility for the health of the thin, fragile, habitable skin of the planet we live upon.

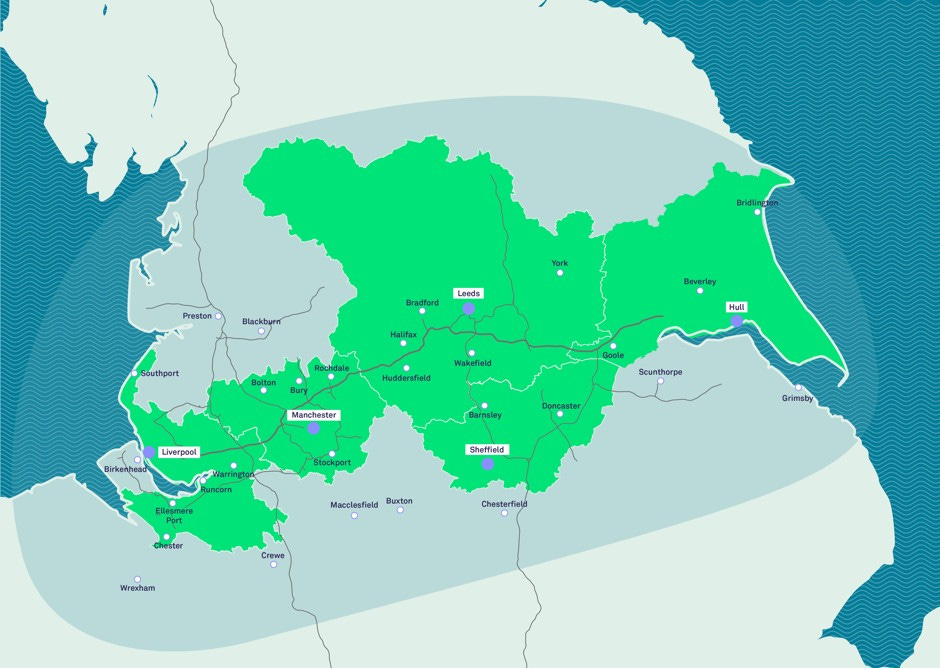

The image above is the Northern Forest, a proposed corridor of trees, 50 million of them, across one of the least-wooded parts of England, surrounding up some of the north’s biggest cities. (Hopefully not just surrounding! As I said in the last newsletter, trees planted in cities cool them in hot weather. We’ll need that effect in the warmer years to come.)

And on another scale entirely, there’s the Great Green Wall, launched in 2007 - an attempt to plant a belt of trees along Africa’s colossal Sahel region, south of the Sahara desert.

This project is designed to unite eleven nations in the service of creating arable land in some of the poorest, driest regions in Africa. It’s certainly not as outlandish as it first sounds, considering that sometime between 5,000 and 14,500 years ago, the Sahara was a mass of grasses, trees, lakes and wetlands - but it’ll still be a colossal undertaking.

When fully underway, it’ll help check the spread of desert, invest in thousands of jobs in sustainable farming and livestock cultivation, and so much more, and it’ll all start with the trees: over 4,700 miles of them, in a 9-mile-wide strip, running right the way across Africa.

(The former travel writer in me is whispering Just imagine walking all that, from end to end. Wouldn’t that be an adventure?)

Green is health and Nature and the way forward. Green means good. Going green is never a bad idea. That’s what green means, right?

It’s 1861, and 19-year-old Matilda Scheueur isn’t feeling well. Not well at all.

She’s working as a florist, and it’s part of her job to go round all the artificial flower headdresses and “fluff them up,” dusting them with powdered Emerald Green paint to brighten up the colour.

(Emerald Green is now the nationally preferred, near-identical alternative to Scheele’s Green, thus continuing the ill-starred scientist’s lifelong curse of never getting lasting credit. Although, considering what happens next, that could be a blessing…)

Now Matilda is getting sicker and sicker. She’s suffering convulsions. She’s vomiting green water from her mouth and nose - and it’s even coming out the corner of her eyes, the whites of which now have a distinctly green tint, as do her fingernails. She’s telling people that everything is starting to look green…

How can this be happening with a safe, everyday green paint that everyone has been using for decades?

But of course it’s happening. Scheele’s Green’s toxicity isn’t news to the doctors that have been tracking its destructive effects for years, trying to raise awareness to no avail. It just wasn’t, you know, news, so there was too little pressure to do anything about it. Plus, this cheap, powerful colour was too important to the fashion industry, to manufacture, to artificial flower making, you name it. What - you expect everyone’s profits to suffer, just because a few lowly workers suffered open sores, organ failure, cancerous growths and an early death? Come now!

At some level, Scheele must have suspected something - certainly at the end of his life, which came in 1786, just eleven years after his discovery of Scheele’s Green. His long habit of testing all the substances he worked with by smelling and tasting them (he’d have got on well with William Buckland) had taken its toll - and he died of kidney failure, brought on by exposure to mercury, lead, hydrofluoric acid, and arsenic. He was 41.

Scheele’s Green (AsCuHO3) is made by heating sodium carbonate, adding arsenious oxide, stirring until everything is dissolved, then adding a bit of copper sulfate at the end. The result is a lovely, natural-looking shade of green that can make lots of people very happy while slowly killing them from arsenic poisoning.

It seems the appalling death of Matilda Scheueur was something of a turning point. For mainland Europe, that is - it appears Britain was much slower to react to the pressure from the Press, from women’s clubs and from the medical professions. It would be 1890 (!) before the last brand of wallpaper using Scheele’s Green would cease production.

(This is why, if you’re buying a house in Britain that’s over 130 years old, it’s probably an excellent idea to strip off the existing wallpaper to check there isn’t a flash of green underneath.)

A particularly bloodcurdling offshoot of this story: the Scottish shipbuilding town of Greenock, which is around 40 miles from where I’m currently writing this newsletter, had at this time an unusual passion for the colour green. (The town’s name is unrelated - it’s probably derived from the Gaelic Grianáig, meaning “sandy place”.)

In and around Greenock, Scheele’s Green was used not just for wallpaper, but also in the paper lining people’s groceries, and even (*deep breath*) as a food colourant, in sweets/candy, cakes and icing. One variety of edible cake decoration, which was advertised as “for the bairnies” (‘kids’), was found to contain seven times the fatal adult dose of arsenic.

The fallout of all this - which must have been truly grim - seems to be a national aversion to green-tinted sweet food. In 1954, the Professor of Forensic Medicine at Glasgow University noted that "fewer green sweets are sold in Scotland than in any other country," adding: "It is astonishing why the idea of green colour in confections should suggest the stupid impression that arsenic is present".

Taking a step back for a second, it’s fascinating how quickly and powerfully the word “green” has come to mean so much more than “the colour green”. Apart from blue meaning gently miserable, I can’t think of another colour being used in this way in the English language. (Please correct me if you can think of another example - even better, if it’s in another language!)

While that’s mainly a good thing, for raising awareness about all sorts of environmental issues, it’s also a super-bad thing. My very first writing gig back in 2009 was for an online eco-friendly magazine based in San Francisco (alongside

and other folk I’m still good friends with), and that was my first introduction to the blight of greenwashing, the ecological equivalent of the way pink has been used to cynically bamboozle women into thinking less about their consumer choices.Greenwashing promotes a lot of really dumb thinking - the kind I associate with the most knuckleheaded kind of videogaming (I’m a gamer here, I’m not dunking on games, but - you know that behaviour when you see it/do it).

For example:

“If we plant all THESE trees, that means we can cut down an equal number of THESE trees! Simple math!”

“It’s okay if we do this massively ecologically befouling thing as long as we offset it - then it basically never happened!”

“We can save the planet if we just plant enough new trees!”

In fact:

“To achieve “net zero” by 2050 using “land-based” carbon removal methods – a category that includes tree-planting, reforestation projects and land management techniques that help lock more carbon in soil – “would require at least 1.6bn hectares of new forests, equivalent to five times the size of India or more than all the farmland on the planet”, a recent analysis by Oxfam found.” - Maanvi Singh, The Guardian

Cutting down old growth forest is catastrophically damaging, and more of a step backwards than new growth projects can hope to offset in the near future. As the World Wildlife Fund says: “Planting trees is good. Saving existing forests is better. Protecting people and nature is best.”

Some big companies have been lying for decades to protect their profits. Not just by omission, but via well-documented efforts to spend huge amounts of money promoting counternarratives that their own researchers had found to be untrue. Considering the very real human impact of the latter, if you were looking for a definition of the term ‘monstrously evil’, I’d say that gets pretty close?

Both the Northern Forest and the Great Green Wall are terrific, smart and hopeful initiatives. I hope they rally people to their cause like few projects in human history.

At the same time, regarding the former, sustainability professional Andrew Heald pointed out to me on Twitter that despite grand promises from its current government, the UK is continually missing its tree-planting targets year upon year - with a more recent report concluding that it’s set to fall short on many other environmental targets as well…

This isn’t really my specific turf - go follow

for an infinitely wiser voice on all this - but as I understand it in a general sense, greenwashing is about preventing people asking questions. The word “green” has become an immensely motivating commercial force as much as a scientific one - and while the best science encourages questions, the worst businesses try to prevent them. They want you to think, Oh, it says it’s “green”, that must mean I’m helping the planet, it must, because why would they be allowed to lie like that? and then push your trolley to the next aisle while wondering what’s on telly tonight.This gives the colour green a unique role in our modern world. It’s a colour with a message. It yells “yes, let’s revel in positivity and hope for the best - but let’s also make sure we’re not kidding ourselves or being tricked”. It’s the colour of respecting credible scientific caution and resisting bullshit as much as it’s about a worldwide celebration of, and investment in, Earth’s natural beauty.

It says, “No, let’s ask more questions here, not less. THAT is the way.”

(Perhaps questions like, hey, is painting arsenic on the walls of my house really that great of an idea? Really? Are you sure?)

So yes, green is indeed good - but it holds its opinions lightly and it asks all the right questions. I hope that message continues to get through.

Images: Hannelore Gärtner/Wikimedia; Woodland Trust; engin akyurt; jeonsango.

I want to buy a Victorian house just to peel off the wallpaper & discover Scheele-green!

Mike, you've done a great job in describing how the complexity of discovery means that unexpected outcomes can yield both positive and negative results.

I think a lot about how Bayer (the drug company) was a dye company previous to inventing aspirin.

I think about today's bazooka-full of money headed to AI, and I'm sure we're going to see lots of Pets dot com failures along with wondrous innovations.