Science Fiction Helps Us Ask The Hardest Questions

The second part of my interview with writer Antonia Malchik

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, an excitable romp around scientifically surprising and wondrous things in search of a good wow.

In today’s edition: the second half of my interview with the extraordinary Antonia Malchik, author of On the Commons (the first half is here) - where we nerd out about why the best science fiction is a great way to talk about really tough things.

It’s dizzying to realise that we’re currently living in the future. Yes, we don’t quite have flying cars yet (the original Blade Runner, above, was set in 2019) - but how about everything else?

Maybe you’ve thought about this before - how folk in previous decades and centuries had no idea that all this was coming. I’m gesturing wildly in all directions, because it’s always fun to look for the inventions that have become so ingrained into our everyday lives that we barely see them. Because, they’ve “always” been there, surely? We can’t imagine a world without them.

Here’s one, courtesy of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994).

In Star Trek lore, it’s called a PADD - short for Personal Access Display Device. Watch old episodes of Next Gen and you’ll see them everywhere, right from the first season.

None of them actually worked, of course. They were all mockups, little more than coloured plastic strips glued to pieces of what I presume was silver-painted wood. (Ars Technica has a great piece on them here.)

If you’re under the age of thirty-five and you’re thinking, “huh, why didn’t they just use actual tablets?” then rejoice, Child Of The Now-Future! You’re about to learn how quickly things are moving.

In 1987, perhaps the closest you had to a tablet was the truly gorgeous, outrageously expensive Cambridge Z88, which I used to gaze at lustfully on the pages of home computing magazines when I came home from school. But it would be two more decades before tablets really took off: from 2 million sold worldwide in 2009 to 20 million in 2010, to their utter domination of the marketplace today. In this regard, the future arrived a lot quicker than anyone expected.

This is the side of science fiction that everyone understands: the speculative (and occasionally goofy-looking) tech, some of which our world has now caught up with. But good sci fi is also about how our messy, baffling, contentious human world will work when things get even more complicated - the politics, the sociological challenges, the forms that capitalism (or its successor) will have to take as non-renewable resources disappear, and the new ways we’ll have to find energy, grow food, raise children…

In other words, it’s about today - only in a highly exaggerated, what-if form.

You may be familiar with two particular forms of speculative fiction: utopian: “everything will be great, hooray!” (which Elle Griffin is studying right now) - and dystopian: “everything will be dreadful, hooray!”. (And in terms of entertainment value, the latter really is “hooray” - post-apocalypse storytelling is just as popular as it’s always been, presumably for much the same reason audiences never tire of going to see horror movies that scare them witless.)

But from this fascinatingly hopeful conversation between authors Michelle Cook and Manda Scott, found via Antonia, I learned about a new subgenre: thrutopian fiction, which seems a little related to the more established hopepunk (here’s a Vox explainer). The idea behind it is: yes, it’s going to be a mess before it all gets better, but let’s actually talk about that process, instead of skipping over it. Let’s think about how we get there, instead of obsessing over “there”.

I used to read science fiction for the spaceships. Now I read it for ideas like this.

That’s why I love Antonia’s take on speculative fiction: not just as a source of fun and wonder, but as a toolkit of potential solutions to the modern world’s biggest problems, and a glimpse of better ways of living alongside each other with dignity and mutual respect & making the most of what we all share.

So, as usually happens when we chat, the second half of my interview with Antonia collapsed into a total nerdfest - and all that’s below, followed by a list of the books we mention.

ps. Antonia is currently running a Threadable reading circle around sci fi short stories, titled The Commons & Belonging in Science Fiction & Fantasy. (I’ve been using Threadable since last year - it’s really great.)

If you want to join Antonia’s reading circle (it’s free), click this link.

Note: you’ll need an iPad or iPhone running iOS 12.4 onwards, or macOS 11.0 (apologies, Android & Windows users, Threadable is still in building mode there!)

Mike: Hi again Antonia!

On the Commons explores ideas of property, ownership and power, and you write so beautifully about them - but you also bring in so many different and surprising themes and tie them in. Which brings me to your love of science fiction - where does that come from? Because that's not, as far as I can tell, a standard interest of outdoor/nature/travel/land-ownership writers. Or is it? Please challenge me on this!

Antonia: That's actually a really good question. I can't remember how I first started bringing sci fi in. When you're writing for an outlet like The Atlantic or Aeon, it's not really something that’s acceptable to do. But I've always been a science fiction fan. We didn't have television service for much of my childhood (we had a TV; my mother worked sometimes at a friend's video rental store and we often rented a VCR and movies from there). But when I was 10, we moved to a place where we got service, and that's when I started watching Star Trek, the original series, after school with my little sister on this tiny black-and-white TV. And I guess my parents were into it, because they took us to a pizza parlour that was doing a big-screen premiere when Star Trek: The Next Generation came out, the very first episode. So we went and watched that–I became devoted to Star Trek for a long time.

But then I didn't read science fiction for years–at least a decade? I want to say maybe longer. I read Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein and all those guys when I was a teenager, a lot of the sci fi classics. And then I remember reading the Foundation series–I think it was on the third or fourth one in the series when this happened–and I was like, really, this is how women are portrayed? It turned me off of science fiction, which I'd loved, for a long time. And later, when I did a Master's in Creative Writing, you weren't really allowed to do genre writing. I think that might be more accepted now, but at the time it was common that MFA programs really looked down on genre writing. You weren't allowed to write mystery or sci fi or fantasy, which seemed silly to me even then.

M: Yes! Because they're not just throw-away “escapism”. It's a format where the writers are just playing with ideas and what-ifs, taking something happening in the real world and cranking it up to an extreme. The Handmaid's Tale, for example.

A: When I started reading Harry Potter sometime after the fourth book came out, I was talking with my older sister about it. We were wondering what it was about Harry Potter that we found so riveting. We talked about how so much 20th-century American literature, or literature in the English language, just didn't seem to have enough story in it. You can go back and read Jane Austen or Charles Dickens or Elizabeth Gaskell, and it's absorbing, immediately. The stories draw you in. But then you get to the 20th century and–I don't have enough literary criticism vocabulary to know what's so unsatisfying to me about a lot of well-known popular literature, but “unsatisfied” is the word for my reaction–and that's when I realized why I gravitated to mystery novels and fantasy. That's where the good stories were. We talked about how it seemed young adult literature felt like it had the best stories. And challenging! I don't want to go on about Harry Potter too much but unlike say, books I love like The Hobbit or Lord of the Rings, where there's a strong element of fate and destiny to it (which you find in a lot of fantasy), Harry Potter was different in making it clear that it was about personal choice–whether or not Harry pursued and fought Voldemort. Yes, there was a prophecy and all that, but Dumbledore kept making the point that it didn’t mean that it was something he was automatically predestined to do–he could still choose to walk away, even if Voldemort forced him to fight eventually.

Having that reality of strong moral choices presented like that, my sister and I both felt we hadn't seen that in fiction in a really long time. I wish J.K. Rowling had taken that lesson fully out into the world we live in, especially when accepting people's full humanity was such an undercurrent in those books. You can make the choice not to spend your legacy denying people’s humanity.

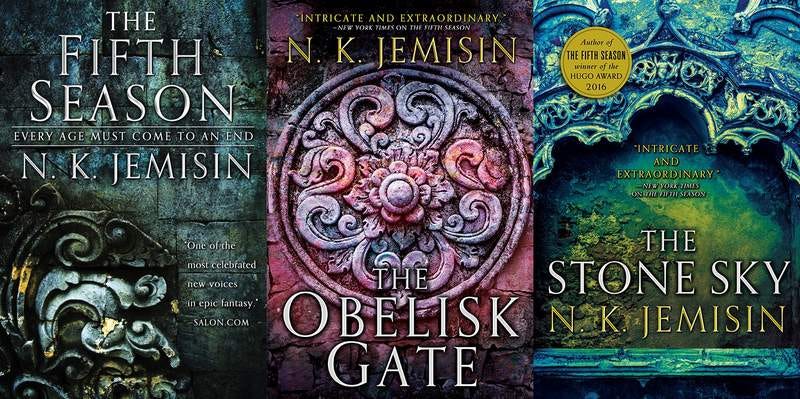

And then a few years back, one of the local bookstore clerks recommended N.K. Jemisin's Broken Earth trilogy to me. That pulled me straight back into science fiction and fantasy. I realised that wow, there had been so many new developments in the genres that I didn't know about, because I just hadn't been paying attention. This new crop of authors are grappling with some really big stuff, and the world-building is incredible. I just finished A Memory Called Empire, by Arkady Martine. Holy cow. And The Expanse series–when I was writing the walking book, I think at the time I was watching the TV adaptation of The Expanse, and also Humans, which unfortunately has been cancelled. I don't know if you've ever watched that?

M: No! I heard good stuff though.

A: I liked that show, it was a bummer to see it go.

So, sometimes you just get really stuck on a huge writing project and my strategy is to go for walks instead of trying to glue myself to my desk. I'll go for a long walk around town thinking, How can I actually demonstrate this idea with an example that helps people feel their way into it? And then something will (hopefully!) come, like, Oh, there was that scene in The Expanse where the Marine from Mars is trying to walk outside on Earth for the first time and she's having such difficulty doing it. You can make it a relatable shortcut. I realized I could play around with that kind of thing–using science fiction to demonstrate some of the more granular biology and mechanics of walking–and see what my editor says, and she didn't seem to mind it. So I kept going.

There's a lot in that story, The Expanse, that talks about things I'm working on, like the commons and private property and management of resources. In The Expanse it's right front and centre because the people who live in the Belt [the real-life asteroid belt between Mars and Jupter] don't have reliable water sources, and they're dependent on other people for air, and are forced to live in a colonial-type situation in relation to the far more powerful nations Earth and Mars that they didn't choose and don't want.

M: And yes, it's people, plural. There are characters in The Expanse that you feel very strongly for, sometimes characters who end up on the wrong side for a while. There is no one “hero”. And that's a thing from early science fiction that I found so exhausting. In Foundation, there's Hari Seldon holding the whole thing up, but within each sub-story, there was always a lone hero who saved the day. Yet in Harry Potter, there's no question that Harry would have fallen short at so many points without Hermione and Ron and the Weasley brothers …

So I feel like our shared love of certain stories, it's the ideas, but it's also that collective effort, the ensemble. Not this lone exceptional superhero type, without whom the world is doomed. I feel because we always read ourselves into characters in stories in some way–and if the protagonist is presented as the only person who has all the answers in the whole world, then what's that doing to our humility and sense of self?

A: I used to love Xena: Warrior Princess, and the reason I loved watching that show so much is because Xena was flawed. Flawed heroes always need help, and she needed a lot of help.

But I'm excited about the newer writers of science fiction. I have this big pile of short story collections that I'm reading through for my Threadable reading circle on science fiction, the commons, and belonging, and it's SO much fun. I asked in a couple of places for women and non-binary people of color who write fantasy and sci fi and got so many suggestions it might take me the rest of the year to read them, or longer. I love Rebecca Roanhorse and Hao Jingfang and Cherie Dimaline and Martha Wells and Nnedi Okorafor. I love the different ways they're able to envision worlds and how people live together, or not, what relationships can look like among people, even who is considered “people”, like in the Murderbot books. I wish my imagination worked like that. I recently read Catherynne M. Valente's story “The Difference Between Love and Time” on Tor, and I have no idea how to describe it but it's just delightful. Valente was a writer one of my subscribers recommended to me and she’s fantastic.

But we've also talked about Kim Stanley Robinson–I haven't read the Mars trilogy, which I know you love. The first of his that I read was Aurora.

M: Oh yeah. That book got me emotional–the part where they're heading home, and the ship is faithfully, even lovingly, looking after them, for centuries. The other side of Artificial Intelligence–what if it's actually kinder and more loyal than any of us are capable of being?

A: What caught my attention was the relationship of the evolved human body with the planet we live on. [In Aurora, hopeful colonists travel to our nearest seemingly habitable planet around another star, only to find its biology is fatal to human beings, forcing them to attempt a desperate, hazardous retreat home.] Which is something I went back to when I was reading about walking, something that most of us don't appreciate and don't even fully understand: We evolved on this specific planet with its specific biology, gravity, life. Thinking about that dazzles me sometimes. Astronauts have a lot of physical problems after a long time in space, like loss of proprioception and bone density. In Aurora, it was so cool and unsettling that they went to this planet, and no matter how many scans they ran, there was just one thing they couldn't detect that the human body could not adapt to, and it had the ability to kill everyone. And that's important. Imagination is a great thing but what happens when we meet our hard limits?

Even the Three-Body Problem trilogy, which actually I didn't love because the characters are paper thin–nice plot, but who are these characters? And it's SO sexist. But there, Liu Cixin writes about the dark forest theory: You're in a dark forest. You hear movement. There are other creatures, other people. They might be hostile. And you won't know if they're dangerous or friendly until it's too late. His point is: what if that's what space is like? What if every species kills every other new one on sight because they can’t take the risk? Not that I necessarily think there are alien civilizations waiting to smash us the second we poke our heads out but . . . that's why science fiction is so interesting.

At its best, it poses challenging questions about what we think “progress” is, and how people will actually live together in the future, and asks us to think more carefully about what we want life to look like a few generations down the line. About responsibility. Technology is fun, world-building is fun, but it's those deeply human questions that keep me coming back. I really love that about the modern wave of sci fi. I'm not keeping up–I won't even pretend that I'm keeping up. I'm probably a decade behind. But it's just so nice to see all these different ideas creeping in …

M: Right! It's why sci fi can feel so relevant–it's allowing us to speak about the sometimes unspeakable-feeling things, the things that immediately polarize conversations. So you present them in a fantastical context, under the guise of entertainment, and it will get people talking because it's not about today, but it is about today. You just smuggled it in. Like the new Battlestar Galactica–well, I should say “newer” because its finale was nearly 15 years ago now–but there's stuff that they did with the plotlines, like how the first episode “33” [probably my favourite 45 minutes of television] was absolutely about 9/11 but as a Brit I only realized this from an interview with [showrunner] Ron Moore. And also they had an episode where a progressive, pro-choice president, a woman, was faced with legislating abortion in a situation when your civilization is just 30,000 people and dwindling by the day. Really difficult questions, and they often tackled them head-on.

[The same can be seen with Ron Moore's new show, For All Mankind on Apple+, which I previously raved about here.]

So if you're on, say, Twitter or Facebook, asking people to discuss these things can get super-heated really quickly, because it's real and often deeply personal to them. But if you can do so in a fictional context? Not real–but still relatable. That's the great power of fiction.

A: Battlestar Galactica asks directly, “What is life, what is a person, who has a right to exist?” And conversely: how do you exist in a world with people who don't actually believe in your right to exist, or think you should only be allowed to exist within a certain framework? That's enormously relevant! Other fiction does that, too. I just feel like much of it has been trapped for a long time by a certain model and expectation of what's considered “literary”, which is unfortunate. There are some writers, like Margaret Atwood, who can break through that barrier. But it feels like very few other writers are really allowed to get that speculative.

M: Right, exactly. And it's easy to sound apologetic, “Oh, you'll like Battlestar Galactica, it's not really science fiction, it's more like a political war drama.” No, it is scifi, Mike, stop it. Yeah, it's this … withdrawing from the reality of what it is? People who say they have no interest in any of it probably could understand better: it's just such a wide-ranging thing. Not just the Boys Own Adventures stuff, men in space with blasters going pew-pew, perhaps ironically called the Golden Age of sci fi, but Ursula Le Guin and Octavia Butler and–you know, there's just so much. I would guarantee that anyone wading in and looking for something that will grab their curiosity, and written in a way that really resonates with them, well, they'll find it.

A: Yeah. Maybe it's like someone saying I don't like soup.

M: *laughs*

A: On the other hand–as we've talked about before–I have plenty of friends who don't read. One of my close friends feels bad because she doesn't read books. And, well, who cares? Don't feel bad! I know that sounds awful coming from a writer and someone who loves books and thinks they're valuable and important, but I feel very strongly that the story is what's important, and however you engage with a story is how you're going to walk through the world with that story. I talked with an undergraduate class last fall and this kept coming up, this question of “How can I write/think/whatever if I don't like reading books very much?” Probably the most important book I've ever read is Svetlana Alexeivich's The Unwomanly Face of War. And yes, it's in book format and I read it, but it's an oral history of real people's experiences. Stories come in all forms.

I love Jane Austen. I'm a huge Jane Austen fan. And I get that same kind of response from people about her as I do about science fiction and fantasy: ugh, romance stories. What makes those books timeless are her observations of human nature and her wit. But do you have to read Jane Austen? No. And if you're not enjoying it, why subject yourself to that? Try one of the movies or TV shows. Her stories make great television! I think she would have been a TV writer if she lived now. Same for Dickens.

M: Absolutely. Also–one of the things I've been thinking about in terms of curiosity and discovering something new is finding a new relationship to a book later in life, a book you think you've “read”. Like, going back as an adult and reading a book you loved as a kid, to find the story transformed. To see what the author was trying to plant in my mind and it just didn't happen the first time I read it, because I was looking for something else. But re-reading is difficult to justify these days because there are so many books. So I'm interested: how often do you re-read things?

A: It depends on the book. I have actually worked hard at giving away a lot of books that I'm pretty sure I'm not going to reread in the future, which has helped. But when I was eight, my older sister introduced me to The Hobbit and then The Lord of the Rings, and I read those every year growing up, right after school got out, and it was utterly my escape. I just loved being in that world, and it was a treat as soon as I finished school. I would spend however many days completely immersed in that world, crying at all the same parts. I still read them and love them. That will probably never change. But it's a really good question. I re-read classics a lot. Jane Austen, Dostoevsky. I wish someone would come out with new translations of his work, because of what you just said about having a different experience. I was reading them a few years ago, and Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls again, and I was thinking they read very much like 19th-century British fiction, which I bet is partly to do with the style of translation from the original Russian. That's just a guess, but I have wondered.

I read a lot of books for research and I go back to those more than I thought I ever would. But I don't reread them as such–it's just following the Post-It notes I've made. I mark those books up pretty thoroughly and that becomes my own way back into them.

M: That sounds far better than my process right now–I usually make far too many notes, and then I throw away a lot of them at the end until I'm left with what feels like the story. I just wish I was a lot quicker at it!

Anyway–there was something you said earlier about using sci fi to tackle hard things. One being: the unknown, that source of so much wonder, but also dread. A thing I really loved about the original Alien (1979)--that feeling of these people stumbling across something they didn't understand and weren't prepared for. And only one of them got away. And at the end, she still didn't understand what the hell she stumbled across, and neither do we. A real sense of humanity poking a toe into the wider sea of the universe, and finding it weirder and more dangerous than anything we'd expected. I wish Ridley Scott had just left it there, with that sense of the immensity of what we don't yet know we don't know. And generally, I love good sci fi for that feeling.

A: Yes. Just thinking about that . . . I always do crave knowing “that thing”, the explanation of what they've seen, and–I don't want to spoil The Expanse books for others, but it has to do with the protomolecule, which you know because you've read them. They don't answer it in the TV show. They finish one plotline pretty well [Amazon's The Expanse only covers the first six books of the nine-book series], but they don't answer that ultimate plot arc of what the protomolecule is and who created it and why it's such a threat to humanity. But it's interesting how powerful that craving is to know what's in a totally fictional world. The answer could be anything, since it's fiction and therefore totally made up, but I still want to know what it is! And I'll accept pretty much any answer as long as it feels generally satisfying.

M: Right. And that information gap is so addictive, between what I've just learned and what it might mean. Like the scene in Breaking Bad where it's a flashforward in time of Walter White taking a big machine-gun out of the trunk of his car. You now suspect terrible things are going to happen but don't know what form they'll take. That kind of storytelling always drags us onwards and fires our imaginations, especially in sci fi - just look at fan theories online. But also: obsession, which has such a bad reputation as a word, but aptly describes renowned scientists like Richard Feynman, latching onto ideas because they're so interested and so in love with possibility. Do you have that same reaction?

A: Yes! I did a mathematics degree as an undergrad, and that gets back to what I loved about it. I remember doing Group Algebra, and the wonder of going through this one set of problems and this whole process to figure this thing out–it's what astronomers use when they're measuring the wavelength of light from a pulsar, I think? It’s been a long time–and I remember thinking, wow, how did we even get there, from the math to a practical application? I'm pretty passionate about math and how it describes the patterns and relationships of the world around us. Someone once described it to me as a human vocabulary for those, which I thought was pretty accurate. How math is taught makes me sad, but that's another subject.

M: So what healthy obsessions are you feeding into your newsletter–and where do you want to take them?

A: So, it's about the commons: land, water, air, data–the shared world that we live in and how we relate to it, how we use it, how we live together, all of which is really, really hard. And how we live together fairly, which seems to be even more difficult. But the core of that is the idea of ownership. Some people get kind of glazed over when I say that, but it's about private property versus the idea of the commons. What we own, and how we own things–property rights, for example, like a right to pollute versus your right to breathe.

I had a book proposal on all this, and when it got turned down by all the publishers, I started working on it as a Substack newsletter. The idea would not let me go–it's maybe more than a year and a half since the proposal was rejected, and the idea won't leave me alone. Thanks to your encouragement, I decided to publish the actual book on Substack as I write it (which I’m starting to do now) rather than just write about it generally. The chapters are on land, water, seeds, data, people, the way that people are still owned all over the world, the human story, and about what kind of history we're allowed to teach…

And just this concept of owning: a totally human creation. A story that has tremendous force in our lives. It's what the legal system is based around.

I was reading one of Willa Cather's books, Shadow on the Rocks. You probably don't know her. She was an early-1900s American writer. The book itself was set in the 1500s, in an early colonial town in what’s currently called Canada. One of the main characters was explaining something to his daughter, and he said in essence, Because the law thinks so much on property, property is all that the law protects. And this saturates everything in our lives to the point that many people don't even really notice it. One of the questions I've been stuck on quite a bit is why trespass laws are so vigorously enforced in the U.S.–you can't set foot on land owned by someone else–but pollution, basically a property right, the right to pollute, is allowed to trespass into our bodies as well as into the commons. (I really should have called the whole thing Trespassing, but a little late now.) The laws around those, around all property rights, are reflective of the stories and values that dominate a society at a specific time. And I think it's time for them to change, for us to start questioning ownership's roots and justifications.

M: Thanks so much, Antonia!

Find Antonia at On the Commons, and sign up to her Threadable science fiction circle here.

Mentioned Reading (with links to Bookshop.org)

Svetlana Alexievich - The Unwomanly Face Of War

Isaac Asimov - Foundation (currently being very loosely-adapted on Apple+)

Margaret Atwood - The Handmaid’s Tale

James. A. Corey - Leviathan Wakes (The Expanse: book 1)

Liu Cixin - The Three-Body Problem (Remembrance Of Earth’s Past: book 1)

N. K. Jemisin - The Fifth Season (Broken Earth: book 1)

Arkady Martine - A Memory Called Empire (review at Vox)

Martha Wells - All Systems Red (Murderbot Diaries: book 1)

Also--have you all read A Long Way to a Small Angry Planet by Becky Chambers? My son loves that book and I loved it too--the AI comment made me think about it--the idea of AI actually becoming something more loving and loyal--I've thought about that too and there are elements of that in that book--it's really such a great, thoughtful, creative, work-- just really well done.

Love this! And this gem: One of the questions I've been stuck on quite a bit is why trespass laws are so vigorously enforced in the U.S.–you can't set foot on land owned by someone else–but pollution, basically a property right, the right to pollute, is allowed to trespass into our bodies as well as into the commons.