Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, attention, wonder, and the power of getting out there and having a go at stuff.

One person who is excellent at trying new things - especially if they’re (a) thoroughly absurd, and (b) a surprisingly effective method of meeting new people that hardly anyone attempts because of (a) - is journalist

- whom you may recall was previously wandering round New York yelling “SKWON!” for the chaotic hell of it.Now, for reasons entirely beyond anyone but her, she’s just spent 24 hours on the New York Subway:

The last thing I do before heading out on my big adventure is drop my dog to stay overnight with my neighbor Shelly. I tell Shelly my plan: I'm going to spend 24 hours straight in the NYC subway.

The rules: I can go wherever I please, chat with whomever looks interesting and pass the time however I like—as long as I don't pass back through the turnstile. Also, I’m only allowed to eat, drink and read what I buy underground.

"Any suggestions?" I ask.

"One word," says Shelly. "Don't."

Read the full account here - and while yes, it’s a ludicrous thing to inflict upon yourself, isn’t it also a fantastic way to rewire your experience of a place you’ve unconsciously taught yourself to overlook?

(Even so - blimey, Anne. What are you like?)

Staying with Crazy But In The Very Best Of Ways:

It's not often that a book proves so influential that it creates (or at the very least hugely accelerates) a national movement.

It's rarer still when that book is the author's only work they publish in their own lifetime.

Enter Waterlog (1999) by the late Roger Deakin.

Its success is a big part of why so-called "wild swimming" (ie. going for a dip in the sea or a river or lake, sometimes in stubborn defiance of what the weather is doing) exploded in popularity over the last couple of decades in the UK, capturing the imaginations of a whole new crowd of amateur outdoors enthusiasts - as well as giving those folk who never stopped doing it a chance to say "oh, I'm so glad you youngsters got caught up at last…").

And yet, it's also just the real-life story of one man, a talented nature writer with a gift for not taking himself too seriously, documenting his swimming journey around Britain: "an attempt to discover the country afresh by swimming through its seas, rivers, lakes, fens; its swimming pools and secret bathing holes..."

If there was water, he'd usually have a go (although he skips the incredibly dangerous crossing over the Corryvreckan whirlpool that almost killed George Orwell).

I love this book so very much. It’s why I started swimming in the sea here in Scotland (one of the best lifestyle changes I’ve made since I arrived here in 2020) - so I hope if you read the first chapter of Waterlog on Threadable (click the button below), it’ll similarly bewitch you with the urge to take a dip somewhere you normally wouldn't.

Go on. Chuck yourself in.

And thirdly, please do not be alarmed but -

I know, I know: what an alarmingly tabloid-like headline.

But the upshot of the story is that according to Noa Leach at BBC Science Focus, Dr Darren Baskill of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Sussex, and an upcoming paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, there is….well….a mysterious object….which is going very fast indeed!….and, erm…it’s baffling scientists?

More usefully: it’s a long way away (400 light years), it’s surprisingly huge (8% of the Sun’s mass, or 30,000 times bigger than the Earth) and it’s moving nearly 3 times the speed of the fastest human-made object ever created, the Parker Solar Probe, which I previously mentioned here.

At this speed, in a few tens of millions of years (not much time at all in the life of the average star) it should be barrelling its way out of the Milky Way and into the black.

To acquire this much velocity and energy, something dramatic must have happened to it. Perhaps it had a close encounter with something in our Galactic Center, which is tremendously crowded with stars (up to 10 million per cubic light year). Or maybe it had a near-miss with a black hole. Or both!

Or hey, maybe it’s a vast hollowed-out rock filled with colossal chambers, one of which goes on forever!

(Okay, it’s not, but I did love what the core ideas of that particular novel did to my tiny brain, and I will never tire of enjoying the memory.)

So, to today’s main story.

Incredibly, it’s nearly a year since I began this season’s look at islands with this piece:

How The Modern World Lost & Found Its Newest Continent

It’s all a messy tangle of half-definitions... As Wikipedia accurately notes, “continents are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria.” (Right, but - whose convention?)

In short: how very, very human this whole issue has become.

I feel like I’ve barely begun to chart the edges of this topic, which is great because it’s a subject I love and I’d hate to feel like most of the fun of discovery was behind me.

But on the other hand - well, here we are, a full year and 45 newsletters later, and I really need to crack on with what comes next, so let’s have a go at wrapping this up.

(However, I’m going to cheat. I want to keep writing about islands and the people who live on them - technically that’d be all of us, but…you know what I mean - so I’m going to keep doing so. The next season will have an entirely new theme that I’m really eager to get started with, and more about that next week, but you can also expect me to circle back occasionally and throw an island or two into the mix, as I’ve done with all the main topics of previous seasons.)

Today, let’s speed up the geological clock and see what coming for us in the long run.

In this case, the best way to look forwards is to peer back at where we’ve been.

Except: “we” is inaccurate. We’re talking about geological timescales here, measured in hundreds of millions of years. Anatomically modern humans have been around for around 300,000 years - and our distant hominin ancestors, the entirety of what you could define as “human,” only go back around 6 million years.

Remaining optimistic about our ability to clean up all the messes we've made for ourselves and the fragile ecologies that sustain us, how long could humans as a species continue to survive on Earth?

“Paleontologically, mammalian species usually persist for about a million years, says Henry Gee, a paleontologist and senior editor at the journal Nature, whose forthcoming book is on the extinction of humans. That would put the human species in its youth. But Gee doesn't think these rules necessarily apply for H. sapiens.

"Humans are rather an exceptional species," he says. "We could last for millions of years, or we could all drop down next week."

- “Will Humans Ever Go Extinct?”, Stephanie Pappas, Scientific American.

With that in mind, let’s stick an extremely generous life-clock on Homo Sapiens Sapiens of 100 million years.

At a scale which includes our very distant hominid ancestors, we’ve still only been around for 6% of the projected lifetime of our species (and as modern humans for just 0.3% of it).

Equated into human terms, with the average modern human living to the age of just over 73 years, that means at best we’re currently less than 5 years old.

As I’m sure you’ll agree, this explains a lot.

But I also find this a surprisingly hopeful analogy. Of course we’re doing a lot of foolish things like engaging in self-destructive behaviour and turning irreplaceable natural resources into this weirdly powerful imaginary thing we’ve invented called “money” - it’s because we’re still too young to know better.

(I mean, this excuses nothing, and takes nothing away from how much we have to learn about becoming responsible and effective stewards of our vanishingly small corner of the Milky Way - but it can at least help remind us why we seem to be such a woefully incomplete work-in-progress.)

But look - we’re still talking about humans, and this newsletter isn’t about them at all, so let’s stop doing that.

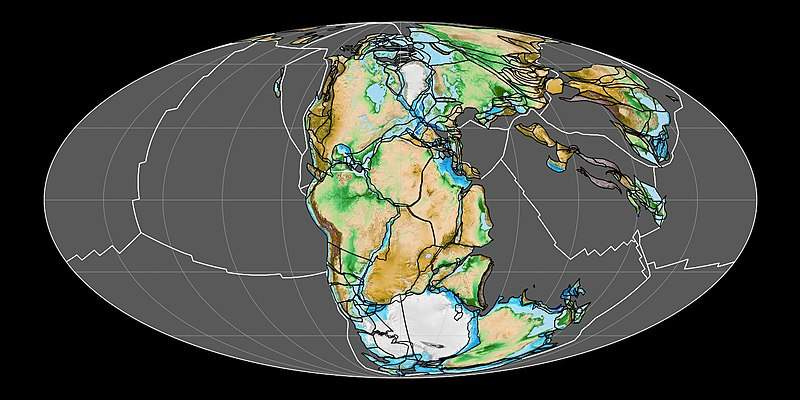

This is the Earth as it’s believed to have looked around 250 million years ago, with the borders of modern continents superimposed to show how it jigsawed together into the supercontinent Pangea (as I wrote about here):

Compared to today, this looks startling lumpy - like wet dough clagging together in the middle of a mixing bowl, instead of the broken-china-like scatters of land we have today.

Before reading my way into this topic, I figured the very rough pattern of our geological history over the last few billion years was of order turning to disorder: the continents drifting away from each other and gradually losing integrity, like the foam on a cooling cappuccino.

Unfortunately for me this is complete twaddle, and yet another sign I’m probably unqualified to write this newsletter. (Sorry, no, that doesn’t mean you can take over. I’m having too much fun.)

The reason is around 4,000 miles (6,370 kilometres) directly under your feet right now - believed to be a mostly solid ball of iron-nickel alloy which, at its innermost depths, is around the temperature of the surface of the Sun. Our planet is not believed to be ‘young’ in the wider scheme of things - but it still pumps out an astonishing amount of energy, in ways geological scientists are only just beginning to understand…

So, forget the cooling-cup-of-coffee analogy - and replace it with a jacuzzi.

For the last 3.5 billion years, the crust of the Earth where we make our home has reflected the buckling, churning turbulence of the mantle’s convection currents beneath it - so everything is on the move, even if we’re far too quickly-lived to usually see it.

However, it’s not just random chaos. There are mighty patterns at work here. One thing most geologists now agree is that we’re partway through a supercontinent cycle, each rotation lasting 300-500 million years.

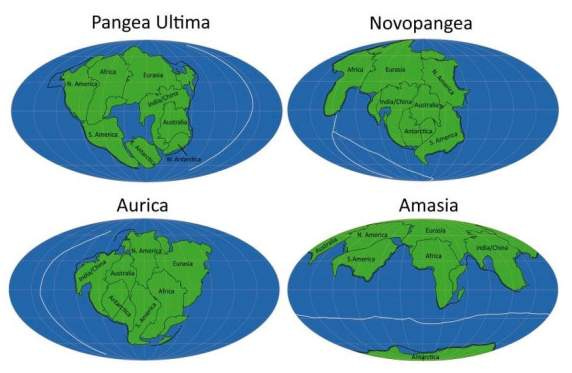

This means that in another couple of hundred million years, Earth should once again have itself another Pangea:

Of the four most popular future supercontinent models currently duking it out (above), the one that most interests me is called Amasia - partly because I like how it sounds like “Amaze-ia” (yes, I’m precisely that low-brow, but fun names are important when you’re going to be stuck with them for millions of years), and partly because it relates to this previous edition of Everything Is Amazing:

Why Everyone Wants What's Under The North Pole

"Across the whole of the Arctic Sea basin, flanked by mid-oceanic and volcanic ridges on either side, is a whoppingly huge belt of continental crust.

How huge?

It's more than 1,800 kilometres (1,100 miles) long, and between 3.3km to 3.7km above the surrounding sea floor, for its whole length, getting to within 400 metres of the surface at its highest point.

Imagine a ridge of mountains as high as the Dolomites, with sides almost as steep, stretching from London (UK) to Belgrade (Serbia) or Detroit to Houston - with a flattened top that's between 60 and 200km wide."

As the Atlantic continues to widen due to sea-floor spreading (creating the longest chain of mountains in the world), the Pacific will close as its underlying plate subducts under the Eurasian continent and the Americas and closes the Arctic Ocean - and eventually the upper northern hemisphere will become Amasia, a single landmass.

This will leave nothing but sea until you hit Antarctica.

It’d be quite the sight:

None of this is settled, of course, and won’t be a long time yet. As geologist Hannah Davies comments in this BBC Future piece: “If I had a Tardis to go and see, I wouldn't be surprised if, in 250 million years, the supercontinent didn't look anything like any of these scenarios. There are so many factors involved."

But whatever it’ll look like, it’ll be a whole new world.

I wonder who will be there to see it?

Images: JPL/NASA; Fama Clamosa.

Fascinating that mammals only tend to be around about one million years. Just another article making me wish I had a crystal ball to see the past and future evolution of our planet!

Not going to have Amnasia about this Substack anytime soon. Right there with you on loving jumping in water and being fascinated by islands.