How The Modern World Lost & Found Its Newest Continent

(Although: what exactly *is* a continent, anyway?)

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and wonder.

Today’s edition is about the boundless mysteries of our planet’s undiscovered islands and some startling new discoveries off the coast of Australia…

But it starts with me falling into Yorkshire’s biggest freshwater lake, annoying a couple of dozen swans and at least one powerful bigot.

(I promise this’ll turn into some actual science in a bit, but for artistic reasons I have to humiliate myself first. Thanks for your understanding.)

The whole thing is my fault, of course. When you’re a teenager in a wooden rowing boat in the middle of Hornsea Mere with a friend, and that friend is daft enough to get to his feet when he’s making room for you to take the oars, the last thing you should do is stand up as well. This would become the second most important thing I’ll learn this day.

So, I stand up - and freeze in horror, as the now top-heavy boat starts rocking violently from side to side. East Yorkshire holds its breath.

If you’re ever in this situation, I heartily recommend cowardice. Don’t assume you’re as sure-footed as Michael Flatley, the kind of person who could genuinely recover a bad situation like this. Don’t try to fight it with your thigh muscles like you’re training for It’s A Knockout or American Ninja Warrior. Just surrender all your dignity and collapse vertically like a released sack of turnips. Hooray! The laws of physics are back on your side, the ghost of Isaac Newton is smiling warmly down upon you, and you’re even in prime position to kick your friend into the water if it become clear that’s the only way you’ll save yourself.

But - no. I don’t do any of that, so the boat flips over and in we both go.

To be clear: Hornsea Mere is not what you’d call deep. In most places you can comfortably stand up in it, and the worst to fear is either tangling your ankles in the weeds under the surface or, far more likely, being mortally wounded by a swan. Both of these gave me nightmares as a kid (especially after a particularly homicidal swan pursued me round the Hornsea Mere car park) but on the whole, it’s a safe place for a family day out.

But try telling that to yourself when you’ve capsized in the middle of it.

My friend and I immediately do what we were born to do: we panic. The shoreline is hundreds of feet away, so we strike out for the nearest land - a tree-sprouting scrap of mud, sand and twigs terrifyingly known as Swan Island.

According to Wikipedia, Hornsea Mere is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest and a Special Protection Area for birds. It accommodates many species throughout the year, and is of international importance for a migratory population of gadwall. This explains why visiting Swan Island is prohibited, if you were stupid enough to want to visit an island patrolled by swans. Maybe less people have landed there than have climbed Everest, or gone into space? (This would make perfect sense to me. Have you ever seen a swan in space? QED.)

My friend and I somehow drag ourselves ashore, retching lake-water and shivering. It’s a cold day, the wind’s picking up and we’re only thinly clad in t-shirts and shorts. I conclude quite brilliantly that our shirts should dry quicker if we spreadeagle them on branches; this proves to be incorrect, but does give them the opportunity to shrink so we can’t get them back on, adding the risk of hypothermia to our already full day.

After about twenty minutes of half-nakedly shouting and cursing and waving our arms at rowers-by (which also helps scare the swans away), we see a motorboat approaching. This is the man in charge of renting out all the rowing boats.

He hollers something incoherent at us through a portable loudspeaker, guns the engine and speeds away.

This is the last we’ll see of him. Later, the third of our group who stayed on land will tell us that when the boat owner stomped ashore, he was muttering something about how he won’t have anything “unnatural between two men” happening on the lake, and how we “should be ashamed of ourselves.” With a thunderous expression he marched into the boat renting hut, handed his keys over to his deputy so he wouldn’t have to look any of us in the face, and went home.

(I like to think he retired shortly afterwards, but I can’t confirm this is true.)

Eventually, my friend and I flag down another boat of rowers. They let us scramble aboard, flapping our sodden t-shirts at the swans to keep them at bay.

One embarrassed, explanations-filled boat ride later (during which I tell my friend that if the boat-owner’s version of today’s events gets back to everyone at school I’m going to move to Australia), we’ve separated to our respective homes to find towels, hot mugs of tea and what remains of our wits.

You’d think that my main takeaway of the day would be something like People Just Need To Communicate Better, or Bigotry Is A Blight On Family Rowing Excursions, or Never Trust A Swan. (Not that I’d ever need reminding of that one.)

But the thing I couldn’t get out of my mind was that it was so amazing that Swan Island was right there, in the middle of a lake in one of Europe’s most densely-populated countries, yet as far as I could tell from afar, and now up close, nobody had ever lived there.

This was a fascination that lodged in the back of my mind for years, fuelled by British children’s adventure stories like Swallows & Amazons, Brendon Chase and Five On A Hike Together, quietly steered me in the direction of geological history and archaeology - and, eventually, a Bachelor of Science degree in Archaeology at the University of York (2000-2004), and now the newsletter you’re currently reading.

In this new season of Everything Is Amazing, I’m attempting to pick up where I left off two decades ago. What I learned back then about islands was how they work in a scientific sense: their hydrological systems, the microclimates and weather - often both hyper-changeable and surprisingly consistent through the year - and the fascinating ways how their apparent geographic isolation makes people think about them.

Let’s be clear: I’ve forgotten a lot of it, I’m already discovering how patchy my understanding was in the first place, and I’m missing all the scientific breakthroughs and updated research of the last twenty years. For all these reasons, I’m thrilled I have the chance to circle back like this.

But this will also be about the human stories, and a search for perspectives I’ve always lacked.

It’s so easy to romanticize island life and rose-tint away the difficulties (just ask the former inhabitants of Scotland’s St. Kilda), yet because it’s commonplace for so-called “remote” places to be painted as lawless and sinister enough to be perfect fodder for murder-mystery stories, islands often get it in the neck. Take Shetland, the focus of one of the BBC’s most popular crime dramas. (Behind that link is the subtitle: “the dark side of one of the most beautiful places on earth.”)

In reality, Shetland is one of the safest places in the British Isles - and as Malachy Tallack says there, the TV depiction relies on “a feeling of mystery and menace that only make sense from afar.”

(For this reason, perhaps the source novels by Ann Cleeves could conceivably be displayed in the Fantasy section of high-street bookshops?)

But the islands I know best - which might not be saying much, as it may turn out - is the archipelago to Shetland’s southwest, Orkney, where I worked for a few summers as an archaeologist on the island of Westray.

It’s quite possible that Westray is about to have its own ‘BBC’s Shetland’ moment - Amy Liptrot’s sublime memoir The Outrun, featuring neighbouring Papa Westray, is now an upcoming film starring Saoirse Ronan, filmed on location last year.

(When I talked to friends on Westray a few months ago, and to the crew of the passenger ferry connecting both islands, they were curious whether they’d see an explosion in tourism or not when the film released, with all the good and ill that might bring to Orkney - but everyone had nice things to say about Saoirse Ronan, who made a point of having a cup of tea and a chat with as many locals as possible. It’s a grand thing when famous people turn out to be that lovely.)

I’ve recently introduced paid subscribers to Orkney in this piece on the tides around Britain, and it’ll be a recurring theme for all-access newsletters like this one throughout this season - partly because I’m obsessed (mea culpa), but also because it’s such a great microcosm of everything I want to write about. Orkney has everything going on.

And one of those things is a noticeable, haunting absence of people.

This is a view of the isle of Stroma (from Old Norse Straumey, "island in the current"), which you’d see away to port if you’re clinging to the passenger ferry from John O’Groats to Burwick, South Ronaldsay.

If you get close enough, you’ll see those aren’t homes, but ruins. Stroma has been abandoned since 1962. The roads are grassing over, the marks in the landscape are fading, and in human terms, it’s becoming an ex-place - rejoining the world’s countless number of uninhabited islands.

In this age of satellite images and digital mapping detailed enough to let you discover yourself on Google Maps, it feels odd to use the word “countless”. Okay, maybe not countable by people, but aren’t there machines that can do it?

Well, maybe that’d work in Orkney - of its 70 islands (in sizes ranging from the tenth-largest in Britain to little more than a fleck of rock big enough to balance a sheep on), just 20 are inhabited.

Maybe it’d work for the UK too. The people to ask would be Ordnance Survey: according to Steve Yeates of the OS National Mapping Agency in Southampton (quoted here):

“Our 1:625,000 scale database shows Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) has a total 6,289 islands, mostly in Scotland. Of these, 803 are large enough to have been 'digitised' with a coastline by our map-makers. The rest are recorded as point features.”

Of those many thousands of British islands, just 200-ish have people currently living on them full-time - which doesn’t sound a lot, until you remember the biggest (confusingly also called “Great Britain”) is on a scale that utterly dwarfs the rest.

But that’s nothing. Geographically speaking, the UK is a piddling backwater scrap of near-as-nowt, as we would say in Yorkshire if we weren’t still in deep denial about it like everyone else in Britain. The UK is vanishingly small, on the global face of things. We’re just a tiny corner of a small neighbourhood.

You know what’s actually big?

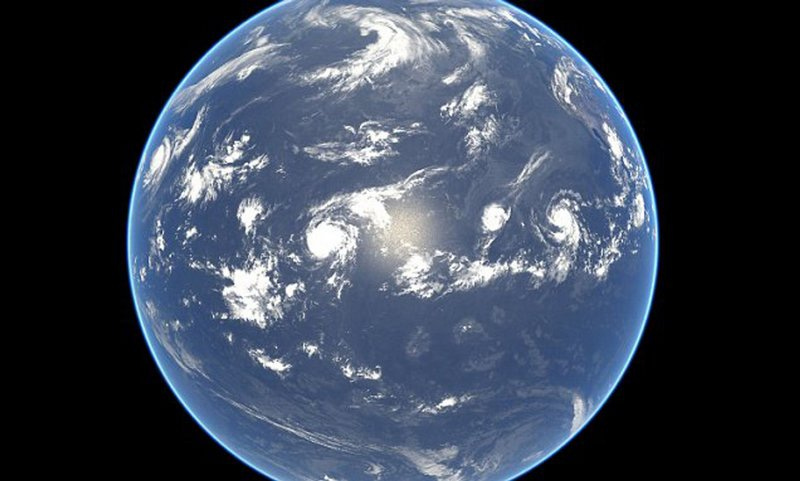

As I said in the introduction to the fourth season, our “Earth” is really an ocean world: 71% of it is waterbound. And in that vast expanse of surface area, our attention is naturally drawn towards the land, the 29% we can live upon, and everything around its edges.

It’s worth taking a minute to look at that NASA’s-eye view of our world up there. How many islands are too small to be seen from this distance? How much land are we really looking at?

You can broadly extrapolate this from looking at some of the world’s most islanded nations. Take Sweden’s staggering number of islands - some 267,570 of them, according to official statistics. (Of that total, just 984 have people living on them. Totted up in this way, Sweden is 99.6% uninhabited.)

That’s in just one corner of Europe, mind. Worldwide, there may be as many as one or two million islands that have a permanent population of zero, unless you’re counting the numbers of animals, insects or bloody-minded murder-swans.

Japan probably wouldn’t question my use of the word “countless” either - the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan just updated the Japanese Coast Guard’s 1987 survey of the country’s coastal territories, which formerly listed 6,852 islands. This new survey? Thanks to recent advances in surveying technology, it found 7,273. Not in total, but extra to the original number - giving a grand total of 14,125 islands. Even with some territorial question marks, that’s still thousands of uninhabited islands that haven’t warranted an official mention until now - and therefore didn’t officially exist.

All this is within the sweet-spot between jaw-dropping and ludicrous that this newsletter loves rolling around in, so I’m very happy to learn this new way our vast planet is stubbornly remaining unknowable.

But let’s briefly look the other way, towards the places where we mostly are.

As you already know, the above map includes the landmass of Eurasia, a large island of deeply happy and contented people where everyone has learned to get along just fine without any problems with each other whatsoever. There’s also the island of Africa, and further to the southeast, you can see…

What?

Well, yes, I know nobody except geographers calls Europe & Asia by that name, but that’s what it’s actually…

What?

No, I don’t know why it has to be Eurasia and not Asiurope. Stop asking silly…

What?

Well of course Africa is an island - it’s surrounded by sea! Well, apart from the Isthmus of Suez, but that’s entirely split by the Suez Canal these days, and that whole bit of connecting land is just so incredibly small compared with the rest of Africa, so…

What?

What do you mean “what about India?”

We have a special word for “the biggest islands on our planet,” and that word is continent.

Oh dear. I’m already wrong, and we’re only one sentence into this. Of course continents aren’t just islands - how would that explain Europe? (Although…where does Europe actually begin and end, by the way?)

A common defence of the naming of Europe as a continent separate from everything else on the Eurasian landmass is that it’s historical convention. Back when Europe was newly invented, the rest of the world hadn’t been mapped properly by us Europeans - and now the world’s stuck with it, because tradition should always be respected, what?

Okay! I’m totally fine with this argument if it means we can have Pluto back. If we’re going to dig our heels into the epistemological sands of progress, I want Pluto, and I want Snickers bars to go back to being called Marathon. That’s my personal line here. Your mileage may vary.

But of course it’s all so woefully inconsistent. Can it be called a hard definition or law when at least one-seventh of the entire data-set contradicts it?

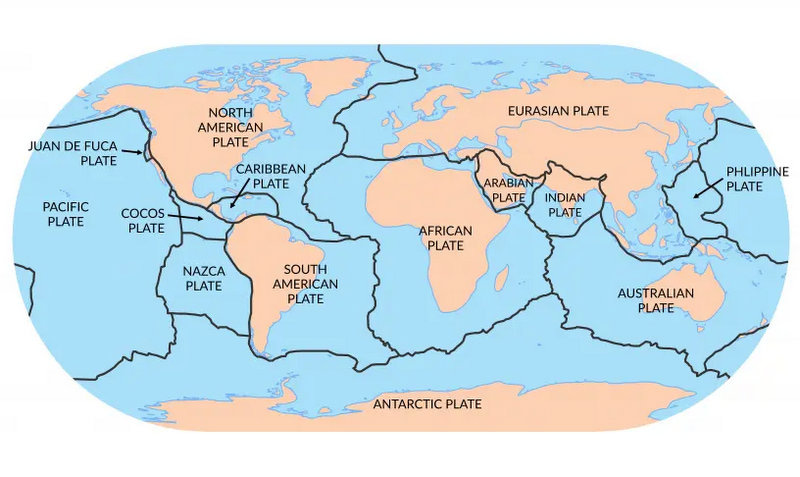

The same applies geologically. This is a map of the major and minor tectonic plates of the surface of our planet:

Putting aside that the definition of these boundaries is itself a human creation and therefore worthy of scrutiny - what does it say about what continents are? Or *squints* what California is?

Perhaps natural mountain barriers are more your thing, like the watershed divide along the Caucasus Mountains that’s often called the easternmost edge of Europe. In which case once again: what about India? Mayhaps you’ve heard of the bloody great range of peaks known as Himalaya, whence resides the world’s tallest mountain? Would that qualify?

(And on that note: the reasons the Himalayas exist is because the Indian Plate, formerly an island, is colliding with the Eurasian Plate and buckling that stretch of crust it’s piling into. Isn’t that even more of a case for treating it as a separate landmass?)

Or we could go with raw population numbers. Surely Europe’s 740-ish million people make it worthy of inclusion? Assuredly! But what about India’s 1.4 billion people - roughly the same population as China?

(I know I have some readers of this newsletter in India, so firstly, HAPPY DIWALI on November 12th, and secondly, how do you feel about all this?)

It’s all a messy tangle of half-definitions - into which we merrily toss the word subcontinent. The most famous of these is what’s often called ‘the Indian subcontinent’, often defined as containing India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Some people happily use this term; others regard it as an veiled insult with more that a whiff of stale imperialism about it, a way to relegate the apparent importance of certain places in much the way that MacArthur’s Corrective Map Of The World tried to address.

As Wikipedia accurately notes, “continents are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria.” (Right, but - whose convention?)

In short: how very, very human this whole issue has become.

But probably the most consistent description - or at least even-handedly unfair to everyone - comes from geology, commonly based on four criteria:

high elevation relative to regions floored by oceanic crust

a broad range of siliceous igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks

thicker crust and lower seismic velocity structure than oceanic crustal regions

well-defined limits around a large enough area to be considered a continent rather than a microcontinent or continental fragment.

That gives us six continents: Africa, Antarctica, Australia, Eurasia, North America and South America.

But it now seems there’s also a seventh! And the reason it’s not a household name is probably all that water currently on top of it.

Around 650 million years ago, at a time of enormous cooling and widespread glaciation, most of the land on our planet was smooshed together into an ever-shifting series of supercontinents.

(This is of course “ever-shifting” on a scale of millions of years. Our own landmasses are changing just as fast - it’s just that we’re so profoundly short-lived that we can’t see it. Fascinating topic! I wrote about it at length for paid subscribers last season.)

For a time, the biggest of these - covering a full one-fifth of the Earth’s surface - was called Gondwana, often called Gondwanaland to avoid confusing it with the region of the same name in India. You can see Gondwana(land) here in its later form, after it had slammed into the ancient Eurasian plate (Laurasia) to form the pole-to-pole landmass we now call Pangea (or Pangaea), which you’ve probably already heard of.

Around eighty million years ago, Gondwana was breaking up to become the world we know today - and a huge piece of breakaway land off what is now Australia started to deform. It stretched, thinning this continental crust and allowing the sea to push inwards - and over millions of years, sinking it under the waves.

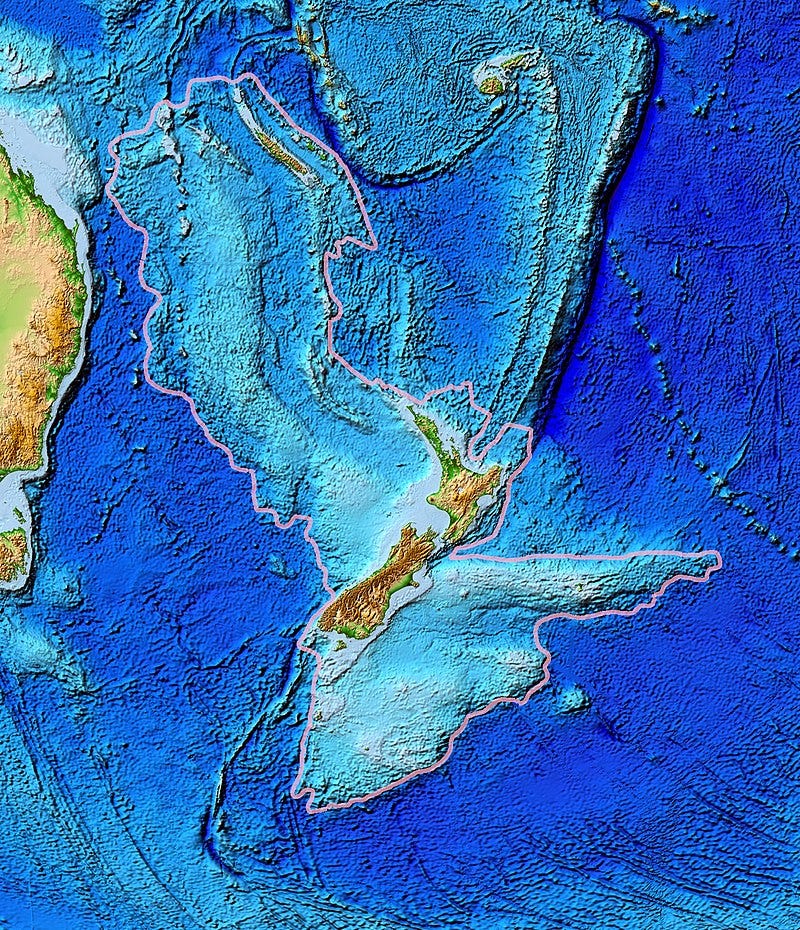

This almost entirely lost continent has been dubbed Zealandia - and it’s inhabited. Around 5.4 million people live there, on what we now call New Zealand, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island. These are more or less the only parts of Zealandia remaining above sea level - just 5% of the original 4.9 million square kilometres (making it around 64% the size of Australia).

If you haven’t heard of Zealandia, have no fear! It was only proposed in 1995, and it’s been a source of amiable dispute ever since: can it be considered a continent if it’s underwater, or should it be called a microcontinent fragment, or something else entirely? Even the name isn’t yet set in stone: Māori speakers would prefer it to be called Te Riu-a-Māui, meaning “the hills, valleys, and plains of Māui”…

But it has, now, been entirely mapped (hat-tip to

, reliable source of sciencey news at ). More formally: “This work completes offshore reconnaissance geological mapping of the entire Zealandia continent.” {My emphasis, because they’re clearly planting their flag here.}So, however we’ll eventually define it, Zealandia has an excellent shot at being labelled our planet’s newest continent. It’ll certainly be fun seeing what new confusions that leads to in the long run.

Thanks for reading!

- Mike

Not yet a subscriber? Sign up here (thank you!):

Images: Oliver Dixon/Wikimedia; David Wright; Mohnish Landge; jcob nasyr.

This newsletter is an island of delight in an endless sea of online content. I love that regardless of where it starts (Capsizing teenage boys! Clueless, homophobic bigots! MURDER swans!) it never ends up where I think it will, and every step along the way is interesting and funny and informative and joyful.

Enjoyable throughout, as always. I recently read that researchers have discovered an underwater canyon in the Antarctic Ocean, thanks to deep-diving seals: they fitted over 200 southern elephant seals with trackers, and they did what seals do and dove down into the ocean, deeper than mapping has thus far reached. After the sealscovery, sonar measurements confirmed the existence of a canyon plunging to depths of more than 2km. Wondering how our seal friends can further help map areas we can't see otherwise.....