Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a wide/wild-eyed, science-driven look at curiosity’s ability to make you go “wow”, to tune out clickbait, and to metaphorically throw you into a pile of leaves for the sheer hell of it.

Today, we’re returning to our season-long look at the science of islands, to take an unlikely direction that I hadn’t considered until I started writing about it. (RIP, all the early drafts of this newsletter.)

But first, a quick update! If you’re a fan of the Trolley Problem, one of moral philosophy’s trickiest and most fascinating ethical dilemmas

…let’s try that again. If you loved or were horrified by that scene from The Good Place where Chidi is driving the streetcar and totally gets splattered with bits of his best friend, you’ll be delighted or relieved to learn that the famous Trolley Problem has at last been solved!

Hat-tip to Jason Kottke for pointing me towards this solution from a bunch of railway workers:

Okay, fine, it’s less a solution and more a Kobiyashi-Maru-style reframing of the rules that sidesteps the whole issue! But stop quibbling - look, everyone lives! What’s wrong with you? Are you some kind of philosopher or something?

Anyway. Now that’s settled at last, let’s celebrate it by getting lost in time at the British seaside.

In 2008 on the south coast of England, Weymouth resident Jane Barrett opened a letter.

The address on the front was that of the guesthouse she ran - Basil Towers - which was presumably why it had been shoved through her letterbox. But, confusingly, the addressee was a stranger’s name, a Mr Percy Bateman:

“When I first looked at it, I wondered why I’d been sent this tiny envelope. Then I looked closer and spotted the date…I couldn’t believe it.”

“Dear Percy. Many thanks for the invitation, be delighted. See you on the 26th December. Regards Buffy.”

The letter was postmarked November 29th, 1919 - and also included a compliments card bearing the names of Mr and Mrs Percival Bateman and Grace Emmie Stewart, and a much more recent note from the Royal Mail apologising for the delay and for any damage that may had occurred to the item while it was in their care over the last, um, 89 years.

After issuing a public appeal for answers, Mrs Barrett was contacted by Mr Bateman’s now-85-year-old daughter Stella, who revealed the real name of “Buffy” was Charles Babbington, a friend of Percy since they served together in the Royal Navy.

It seems that Percy and his girlfriend Grace - later his wife & mother of their two daughters - were hosting a Boxing Day gathering at their home at 22 Abbotsbury Road, Weymouth, and would Charles like to come along? (Oh do say yes, Buffy.)

It’s unknown if the reply reached Percy by any other means, because it certainly didn’t by this route. As for the Batemans, they temporarily moved to London in the 1920s because of Percy’s position as an armament supply officer, then retired to Weymouth accompanied by Stella - and that’s where Mr Bateman died, aged 72, in the 1960s.

And in all that time, the length of at least one richly-lived human life, that letter remained almost frozen - not lost, as it turned out, but moving so slowly towards its destination that almost a century would pass until it arrived in an unrecognisable world that had forgotten it existed.

Nearly 70 years after Charles posted his ill-fated invitation, the Voyager 1 spacecraft launched from the NASA Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida, and started its astoundingly long journey out of our solar system.

It’s worth pausing here to appreciate the brilliance of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which keeps building spaceships that vastly outperform their initial mission goals. Both Voyagers 1 and 2 were designed to study Jupiter & Saturn and their moons up close - a two-year mission within each craft’s 5-year window of operation. But not only did they prove much sturdier than planned, they were also upgraded literally on the fly, as mission scientists and engineers used remote-control reprogramming to extend what was possible and ‘patch’ away technical limitations.

The same would be true of many other JPL craft, including until just last week the Ingenuity Mars helicopter (5 flights planned, 72 racked up) and, between 2004 & 2010, the Spirit Mars Exploration Rover - meant to run for just 3 months, it actually kept rolling for another 6 years, with some assistance from a lucky “unexpected cleaning event” when a Martian dust-devil blew its solar panels clean.

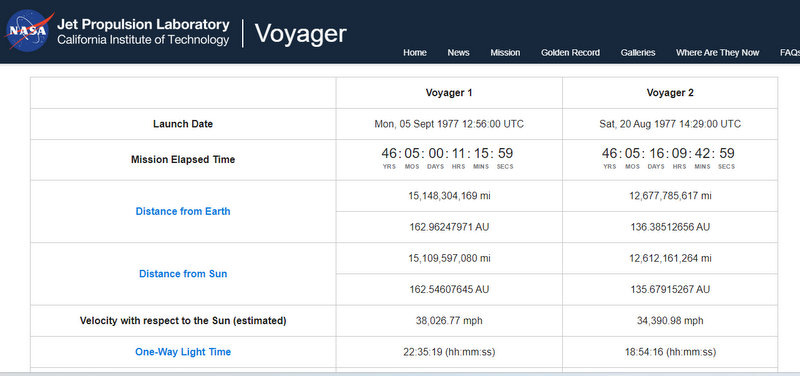

But meteorological windfalls aside, it’s almost always the brilliance of the folk at JPL who find a way to keep things going. Take these astonishing figures from JPL’S Voyager mission status page, live at the time I’m writing this:

(JPL has already secured its place at the top of the history books dozens of times over - but I hope part of its legend is how efficient it is at getting maximum value out of its modest funding in the most brilliantly imaginative ways possible. Imagine if every organization worked this cannily and thriftily?)

Alas, Voyager 1’s extended mission is at last about to hit its hard limits: its scientific instruments rely on radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) running on Plutonium-238, and somewhere around 2025 they’re going to run out of power. On top of this, its flight data system now seems to have developed a glitch, meaning it can receive orders from Earth but can’t transmit engineering and scientific data back.

Sometime soon, the spacecraft will go quiet, and will take its gold record of humanity out into the darkness, in search of what awaits.

But all this isn’t happening very fast. Or rather: in once sense it is, because for a time the Voyagers were the fastest moving human-made objects in the universe - but NASA’s recent Parker Solar Probe has just broken that record by a factor of 10, already achieving a nearly unimaginable speed of 394,736 miles per hour - and next year hopefully beating that by another 30,000 mph.

(To put this into perspective: next time you stand outside looking up at the Moon, imagine a ride that would get you from here to there in just over half an hour.)

But in the other sense, the Voyagers have barely left home. As I explained here, they’ll take tens of thousands of years to fully leave our Solar System. By the time Voyager 1 has travelled for the length of time it took for Buffy’s letter to reach its destination, the spacecraft will still have travelled, in the wider scale of things, absolutely nowhere.

To reach our closest star - Proxima Centauri, around 4.25 light years away - Voyager 2 is going to need around 70,000 more years, which is roughly the amount of time we’ve needed as a species to migrate out of Africa (and, perhaps, the point when our population numbers crashed so dramatically that there were just a thousand breeding pairs of Homo Sapiens on our whole planet).

So what’s the answer, if we want to explore this ‘final frontier’? How can we bridge these near-endless, near-empty spaces between the stars?

We could certainly try going much faster!

That’s a video by the Limitless Space Institute, a non-profit encouraging research into human exploration beyond our Solar System - and I saw it because it was featured at Aeon, probably the internet’s best source of rigorously thoughtful “wow!” material like this.

If you’re skimming this newsletter in your email, please do click through to that video and watch it. Please do that. It’s beautiful, gorgeously well-presented, and it might make you feel Hugely Big Things.

Of course, it’s all science fiction right now. It’s true that the middle ship, the one powered by “the Sun for a heart,” just got a little closer to reality with the recent news that the US National Ignition Facility achieved a fusion reaction that released almost twice as much energy that was put into it - but a working fusion power-plant on the ground, let alone one in a spaceship, still seems a long way off.

(Plus, while it’s tempting to think of such a spacecraft that can just continually accelerate until it’s moving almost as fast as light, unfortunately Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2 tells us that the closer to light speed we travel, the more energy we’ll need to put in to keep accelerating, until there’s no practical way we could ever generate enough to continue. Equally problematically for the ship’s occupants, time would dilate more and more for them, until thousands of Earth-years were flashing by in subjective minutes, then millions, and then eventually, to their utter horror…oh, just read the Hugo-winning hard science fiction novel Tau Zero by Poul Anderson, which has now given its name to this research foundation designed as a successor to NASA’s Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Project.)

But the most speculative part of that video is the most inspiring bit, right at the end, when the Spaceship Of The Future bends space around it to leap majestically forward, exactly like…

Yep - it’s a warp drive!

Instead of being constrained by the speed of light, these ships would use FTL (faster-than-light) drives to warp the fabric of space fore & aft, so the universe essentially comes to the ship, while getting scrunched up along the way - imagine dragging handfuls of table-cloth towards you to reach the salt & pepper, although…that’s probably a regrettably clumsy analogy and I should be thrashed with a mathematician’s slide rule.

The Aeon piece writeup says this is “theoretically possible” (the warping, not the thrashing). And there is indeed a real theory! It was first proposed by theoretical astrophysicist Miguel Alcubierre in 1994, and further explored here by physicist Harold White at NASA. Only thing is: it requires either “negative mass” or “negative energy”, both of which are the kinds of things that look neat & tidy in equations and like unimaginable nonsense in the real world.

(For all that, Dr. White has recently released a paper in which he theorizes it might be possible to create “a real, albeit humble, warp bubble,” around one nanometre across. So maybe it’s just my imagination that’s at fault here.)

For now, these remain intriguing ideas that require a lot of hand-waving and planet-loads of question marks about how catastrophically unpredictable all this could become. Here’s my favourite of these, via Wikipedia:

“Brendan McMonigal, Geraint F. Lewis, and Philip O'Byrne have argued that were an Alcubierre-driven ship to decelerate from superluminal speed, the particles that its bubble had gathered in transit would be released in energetic outbursts akin to the infinitely-blueshifted radiation hypothesized to occur at the inner event horizon of a Kerr black hole; forward-facing particles would thereby be energetic enough to destroy anything at the destination directly in front of the ship.”

This would turn warp travel into a real-world demonstration of this principle from Douglas Adams:

“Nothing travels faster than the speed of light with the possible exception of bad news, which obeys its own special laws. The Hingefreel people of Arkintoofle Minor did try to build spaceships that were powered by bad news but they didn't work particularly well and were so extremely unwelcome whenever they arrived anywhere that there wasn't really any point in being there.”

(I hope astronautical engineers of the future continue to read Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy. While it remains in print, I don’t think we need to panic just yet.)

But staying with the theoretical physics - there’s a huge problem there too.

Any superluminal (FTL) model of travel will have to overturn our current understanding of the nature of reality (hey, no biggie), which states that because the hard limit of light speed underpins everything, if you exceed it, you break causality - the relationship between cause and effect. This rapidly unravels…well, everything, but particularly everything as we humans experience it, and in particular our understanding of the ‘arrow of time’ and how it only ever points in one direction, so we don’t end up going back in time to accidentally murder our ancestors, or bang out infuriated replies to emails that other people haven’t sent us yet, whichever feels more anxiety-inducing to you today.

For a layman like me, this is a migraine-inducing mess. So let’s cautiously say that one thing is clear: we’re probably not going to have a workable warp drive anytime soon - and if we do, something even more amazing will have to happen first, which is that our understanding of how the universe works will have to be comprehensively overhauled from the smallest scale upwards, which is - a lot to presume, frankly.

The upshot is that there’s currently a lot of doubt amongst scientists and researchers over whether FTL travel - or FTL anything - is the least bit possible, seemingly with the bulk of informed opinions landing on the “nope!” side.

(Of course, that’s not to say that they’re right! This page is a good jumping-off point to remind you that the path to scientific enlightenment is far from a linear one and involves many false starts. Nevertheless, the sheer scale of scientific reappraisal that FTL would require should give anyone pause, and it’s certainly achieving that right now.)

So what does this mean about our beloved fictional space empires of the future?

This is a screenshot from my favourite “4x4” space empire videogame, Stellaris.

Putting aside the obvious absurdity that the whole map is in two dimensions, it’s following the classic science fiction idea of one of our historical world empires extrapolated forward into the future, with a classic core (“homeworld”) and a periphery, and reliable methods of travelling and communicating between each, and some kind of enforceable outer boundary keeping it all in (and presumably, keeping other stuff out).

Stellaris is a wonderful and deeply satisfying game. And it’s also a great example of a terrestrial, Earth-bound model of human imperialism copied & pasted over the universe with little awareness - or at least a lot of fudging - of how incredibly different a space empire would have to be.

For starters, there’s only one way this would be possible in the real world, and that’s FTL. The speed of light would never be fast enough to allow it.

This is why science fiction authors quickly brush over this plot-point. Star Trek has subspace for its communications and warp drives for everything else; Orson Scott Card’s ‘Enderverse’ and Ursula Le Guin’s Hainish universe have their ansibles. Asimov’s Foundation series has its ‘ultrawaves’ and ‘hyperwaves’ - and, in the Apple TV adaptation, a black-hole-powered starship, which sounds like a terrific idea and not insanely, recklessly dangerous at all.

(Of course, there are also “stargates” - that popular trope of artificial ‘wormholes’ in space connecting different parts of the galaxy to allow instantaneous travel, an idea which many scientists will happily file under “honesty, probably not?” But even then, someone would still have to go there first, to build that stargate so it can safely connect to the other end. You still need FTL spaceships for this! Well, unless you’re relying on ancient abandoned alien gateways, which opens a whole new can of - look, my headache’s coming back, let’s move on.)

But what really haunts me and thrills me in equal measure is the idea that we never go superluminal. We never break the light barrier in any practically useful way, not even with our communications - and so we’re forced to accept that our own biology and the underlying physics of the universe have limits we can’t push beyond.

(Take the modern darling of speculative intergalactic comms, quantum entanglement, subject of the 2022 Nobel Prize for Physics. At first glance, it seems like FTL in action - but for extremely complicated reasons that seem to boil down to “all you can do is observe but you can’t force a message through it,” it seemingly can’t be used to outpace the speed of light.)

Where would a universe without FTL travel leave us?

I’d say that unless something changes very drastically indeed, it leaves us as a hyperlocal interstellar species, incapable of being much more as the creatures we are right now.

We could spend thousands of years spreading out into our solar system, tens of thousands more reaching the stars closest to us, our hands full with challenges we haven’t yet imagined, reappreciating what we already have at home, and saying goodbye to colonists that will never return in our lifetimes and take years or even decades to report back to us - until they’re not us at all, they’re them, and they do things very differently over there.

It means we’d still be the islanders we’ve always been on this world. And maybe that’d also be true for any other potential forms of life out there, each of us currently too far over the horizon to imagine ever being able to visit in the little time we have?

And if so, if we finally hear from them, or they from us, it wouldn’t be in the form of warships hovering over capital cities and bullying us into joining their galactic-scale territorial wars, in that classic oh-so-human style. Instead, it would be the equivalent of finding a fossil washed up on the beach (or an RSVP from a different age) - a tantalizing glimpse of a world already long gone that isn’t and never was “ours”.

Perhaps it’d also be a reminder of how relatively inconsequential we are, here in this fleeting moment and in this speck of a cosmic backwater, the galactic equivalent of “an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a blur of traffic passing on the highway, as a lighted window at dusk.”

I reckon we could do a lot with that kind of humbling realization - maybe even using it to try to put aside some of our most absurd, outdated and imperialistic notions about “conquering the galaxy,” so we could begin the difficult task of recognising our true place within it, and, at long last, learning what we’re actually capable of.

Now that might be a future worth exploring.

Images: Bekah Allmark; NASA/JPL-Caltech; Klemen Vrankar.

I need to get this out of my head so I can think of something else: a "generation ship" is a really, really, really bad idea. Not only for the practical reasons such as how to feed and clothe and keep alive generation upon generation of humans; nor the scaling problem of having a large enough population to avoid inbreeding; nor the psychological and political problems of still having a working society after all that time. There's also the ethical problem of the first generation of astronauts committing many generations of their descendants to a life that begins and ends on a ship, a choice that they had no say in and may well resent.

There is, in fact, a much more practical approach. Instead of sending expensive, fragile, ill-tempered humans, send eggs and sperm on board an entirely automated (and self-repairing) ship. We know they can be frozen and emerge viable, so it's not much of a leap to do so for the thousand years of a trip to the stars. We could send millions of sperm and eggs ensuring genetic diversity in a much smaller, cheaper ship, and have robots incubate, deliver, and raise the first generation of colonists. And because these children will be educated from a comprehensive library that came with them, you don't have the "cultural drift" inevitable in generations of shipboard life so that you don't risk colonizing the galaxy with literal Space Nazis.

BTW, I am currently writing a novel in which this brilliant idea goes horribly wrong, so if anybody wants to steal it, they have about eight months to get there first!

Well! I AM a Philosopher and say an answer to this problem (whose literature is grossly inflated) is very simple and doesn't require improbable requirements. The Observor simply throws themself on the rails, derailing the train. A natural response to save one potential loss of life or five. Suicide? In a technical sense, yes, but imagine the scenario where you yourself see a grizzly chasing your child (or anybody's child for that matter). You wouldn't stop to ponder. You would immediately step in to divert the bear's charge. Now just substitute train for bear and derail for divert and the logic is apparent. Why doesn't anyone use this approach? Because the designers of the gedankenexperiment can alter the terms-putting the Observor in a remote viewing tower with a switch control at hand. So much for my solution! But it still operates in the grizzly gedanken at least. Actually the U S. are currently in a trolley problem dilemma with the populations of two countries bound on the rails.