When The Bubbles Go Downwards

"It was as though a thousand invisible hands were clutching at my legs..."

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity, wonder, and the importance of trying lots of different stuff for no immediately obvious reason.

This week, I discovered something on Threads that I desperately hope is true:

I did some searching, and while it’s been doing the rounds as a meme for a while now, it also doesn’t seem to have a credible source. One huge red flag: the “London Genealogical Society” doesn’t exist. The closest thing seems to be the Society Of Genealogists, which commented on it in a Facebook post from 2021 that links to a now-dead article on its own site. I will pop them an email to ask what they wrote.

So, this could be complete twaddle! But if it’s fake, it’s still high comedy (I particularly like the mental image of Turnip Shepherd, and Ferret Weaver sounds spectacularly dangerous) - so in the absence of definitive proof, and because I’m 52 and the red-ringed entry makes me feel uncomfortably seen, I’ve shared it with you today.

So, onwards!

Today I have a previously paywalled piece from last year that freaked out quite a few of you - so I’ve now decided to send it to everyone for the maximum bloodcurdling horror. You’re so very welcome.

It’s a coda to season 4’s exploration of the nearly three-quarters of the surface of our planet we tend to overlook, with its 65,000km-long mountain range and its underwater ‘lost cities’ and ancient flooded landscapes and all sorts of other stuff - and it nicely fits with this season’s look at the science islands, too.

It’s the answer to the alarming question: what do you do if you’re taking a dive, and all your air bubbles start to go downwards?

It’s 2000, and professional wreck diver and author Rod Macdonald is about to feel the pull of the abyss.

He’s currently stood on top of an underwater mountain, 30 metres below the surface of the narrow strait between the Scottish islands of Jura and Scarba - and the tide’s about to turn:

“It was an odd feeling to see all six of us there, and I imagined how it must have looked if you could somehow have stripped away the water. Six tiny specks of humanity, standing on the 100 feet wide table top, of a 200-metre (650 feet) high pinnacle.

As we collected on the plateau, I noticed a perceptible change in the direction of the current – it felt as if someone had thrown a big switch. One minute the tide was dropping off gently in the one direction. The next minute you could feel it starting to pick up rapidly in the other direction. There are titanic forces at work here.”

- from “The Darkness Below” (excerpted on Threadable here)

We live on a liquid world. Not just in the sense that 71% of it is underwater, but also in the way that everything is moving. Everything’s on the move, powered by horrifying amounts of energy that our minds just slide off.

Partly this is because it’s easy to ignore: for example, the sky is usually too insubstantial to do much more than tug at your jacket or blast some rain up your nostrils. (Or make a few extremely-uncloud-like clouds.)

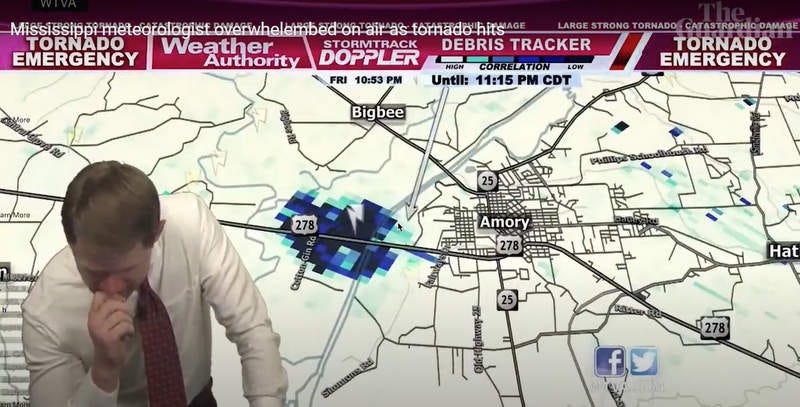

But when it’s someone’s job to really know what’s going on, their reaction tells a story - which is why this clip of WTVA meteorologist Matt Laubhan tracking the tornado that ripped through the north of Amory (Mississippi) is so unsettling.

Water is no different. Most of the time, well, it’s just there, sitting in or upon the land in a way it’s easy to assume is static, uneventful and mostly predictable.

Except - take seas and rivers, creeks and inlets, races and cataracts, and the half-forgotten words for them that Robert Macfarlane recently unearthed (or whatever the aquatic equivalent of “unearthed” is) for his celebratory Landmarks:

tolg (“to sputter, vomit, as a mountain torrent - Gaelic”)

speat

cartage

gulsh (“to tear up with violence, as a stream when swollen with floods - Northamptonshire”)

cymer

ffrwd

aker

land-shut (“flood - Herefordshire”)

…and the magnificently emphatic burraghlas (“torrent of brutal rage - Gaelic”).

The power of these lost words - the meaning of them, and just the raw sounds of them - are great reminders of what water’s really capable of.

Frankly, many of us need reminding. I consider myself stupider than average when it comes to understand natural waterways (what little I’ve learned is via the superb How To Read Water, by Tristan Gooley) - but even I know to beware the most obvious warning signs, like those flattened, oily-looking patches on the ocean that suggest where the current is fast enough to defy the surface push of the wind...

And if you’re out there without mechanical assistance, it really doesn’t take much - as surfer Matthew Bryce discovered in 2017 when he was dragged away from the Scottish coastline and spent 32 hours clinging to his board in the Irish Sea, before being rescued off the north Antrim coast.

As much as I love swimming and messing about in boats, I have…what I hope is a sufficiently healthy respect for offshore currents and fast waterways, knowing that every litre of that water weighs around a kilogram - and since I live in a part of the world covered in rock that was scooped away like ice-cream during the Last Glacial Maximum, I only have to look around for reminders of what it can do to even the hardiest materials.

In whatever form it takes, when water moves laterally with its full force, it’s a blood-curdling thing to behold.

But that’s nothing compared to the water that pulls you down.

“I looked down at the rock I was resting on and sure enough, as if on cue, the one or two small crabs around my feet just made their way into little crevices, braced out their claws and seemingly disappeared. In fact, all life seemed to disappear from the pinnacle simultaneously. The all too brief moment of calm had passed and the residents of the pinnacle were preparing themselves for the next six hours in the maelstrom.

If the locals were getting worried, I thought, our team of six divers should be getting out of there.“

Between Jura and Scarba, the waters of the Scottish Atlantic are squeezed - by the narrowing width of the Strait, and from below, as the sea floor rises to that pinnacle (really more like a buttress) just 30 metres short of the surface, before plunging down towards a deep hole on the other side.

What happens in these conditions is that during the racing tide, a huge line of standing waves emerge, up to 9 metres tall and foaming continuously in place - and, a little further out, a roaring, thundering, terror-inspiring monster the Greeks called Charybdis, and which the rest of us call a maelstrom.

The whirlpool of Corryvreckan is the third largest in the world, behind the ones at Saltstraumen near Bodø, Norway, and at Moskstraumen sea near Norway’s Lofoten Islands.

It’s entirely delightful that they have such big, dramatic names, proper mouthfuls containing all the appropriate face-noises. If it doesn’t sound like it could be performed by Metallica, it’s not a proper whirlpool, I reckon. Just imagine if they had names like “the whirlpool of Milton Peevly” or “the maelstrom of Wetwang”. I know, I digress, but these things are important.

Also, it’s something of a misnomer to say “whirlpool,” because that suggests permanence and the presence of just the one - but there are many, and they appear and vanish again with the tides in an unpredictable, chaotic way. That’s the nature of whirlpools in the real world.

You can see an explanation of how the buttress (locally nicknamed "the Hag”) creates the conditions for whirlpools in this video, which seems to be based on sea-floor scans taken by the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) in 2012:

And when a tide floods the channel with its waters rushing west to east, racing over the Hag and towards that distant abyss at the 219-metre lowest point of the whole Corryvreckan channel, that tidal water goes downwards.

“Dave and I however couldn’t resist the temptation to fin over to the edge of the pinnacle and look over the side, down into the 200-metre deep abyss. Of course, in the limited visibility we could only see about 25 metres down the side – deeper than that was just an ominous uniform black. The bottom was well out of sight.

As we held onto rocks and peered over the side of the pinnacle I became aware that my exhaled bubbles had stopped rising upwards – as they had done throughout the whole of my diving career. For a second or two, some bubbles were held motionless in front of my face. With my next exhaled breath the bubbles started to slowly sink downwards over the side of the pinnacle. As I continued to breathe out my bubbles started going downward more and more vigorously.

It was a very surreal experience and it was certainly time to get out of this dangerous place.”

Not far from my family home in Yorkshire is a stretch of water that’s regularly described as one of the most dangerous waterways in the world.

You certainly wouldn’t think so, seeing it on a sunny day like this:

But if you jump across the gap for a lark, you’re probably risking death. (Probably. There are a lot of legends and tall tales that swirl around this place - but the science is pretty clear: it’s horrifically dangerous.)

It’s called the Bolton Strid, and it’s a short section of the Wharfe, a broad, mostly lazy river that winds its way out of the Yorkshire Dales and runs for 65 miles before it’s swallowed up by the Ouse. Only - this isn’t what the Wharfe usually looks like. At the start of the Strid, the river’s around 90 feet wide. Just a short distance away, it narrows to less than 6 feet.

And yet the same amount of water is travelling through each section.

The river deals with this by more or less turning itself sideways. That volume of water is compressed and speeded up, and currents form - chaotic, turbulent, but with a corkscrewing, downwards tendency.

This is supremely bad news if you go in, because at the sides of the Strid, the water has ground away ledges and pockets, so the base of the river is raggedly wider than it is at the top.

This means if you tumble in, you’ll be battered around for a while, against all sorts of rocky protrusions, and when all the fight has left you, the current will take you down and hook you under the rock.

YIKES.

At least, that’s the theory. The Strid myths are thick in those parts, and everyone knows a man who talked to someone at the pub who once heard about someone who saw, with his own eyes, a man pulled right under, along with his horse! They’re probably still down there!!! And so on.

But the New York Times covered it here, and so did Atlas Obscura. And YouTuber ‘Jack a Snacks’ (I’m hoping that’s a pseudonym) caused a stir in 2021 when he tested the depth of the Strid with a sonar device and concluded it went down a whopping 65 metres - which is twenty metres taller than London’s Tower Bridge.

(He’s recently been in communication with people who claim to have dived the Strid in the 1970s, and they’re claiming it’s no deeper than 10-12 metres - so, plenty of unresolved question marks about the whole thing. But I don’t think it matters at what depth you’re pinned under an underwater rock in a rushing torrent. It’s all a terminal nope.)

Similarly, Corryvreckan is so frightening not just because the current might pull you under, but because it might hold you under.

For the Channel 4 programme “Equinox: Lethal Seas” (2000), a documentary team from Scottish independent producers Northlight Productions threw a realistically weighted mannequin into the water near the Hag during the flood tide, wearing a life jacket with a depth gauge. When they recovered it half an hour later, the depth gauge had stopped taking readings beyond 200 metres - with evidence of being dragged along the bottom for a great distance, presumably after the downward current worked like a waterfall to hurl it all the way down to the sea floor before pulling it onwards…

So when a highly experienced diver like Rod Macdonald says he’s getting nervous, you can certainly understand why.

“We had been warned that the first 10 metres of the ascent would be difficult, and right enough, as I stepped off the top of the pinnacle it was as though a thousand invisible hands were clutching at my legs and trying to pull me down. It was quite an unsettling feeling and initially I had to fin hard to make any headway upwards.

The task of managing the ascent however soon absorbed me as I kicked my legs and simultaneously wound in the slack on my reel, essentially winching myself up towards the surface.”

Rather you than me, sir.

Click here to read Rod Macdonald’s hair-raising account of diving into Corryvreckan on Threadable.

And “The Darkness Below” is available here, or from the usual places (eg. Kindle.)

Images: StockSnap/27551; reddit/Pamart.org; Wikimedia/Walter Baxter; ilya montdryk; Wikimedia/Tony Page.

I love reading and hearing about the experiences of folks who go down in places like this, and I'm so glad I'm on Team Nope.

Ferret Weaving? Did you just pop that one in to throw us off? There's no ferret weaving on that list!