Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing - a newsletter about science, curiosity and the joys of a good, hard Wow.

[IMPORTANT NOTE: This is going to be a long one, with a lot of images, so it’ll probably get chopped off at the bottom by your email provider. Click on the title above to open the Web version & read it all!]

To start this edition, here’s your haunting idea of the day, courtesy of a recent piece by Abigail Beall at New Scientist…

A rogue planet is one that's escaped the gravitational clutches of its home star (or other body with a similar mass, like a brown dwarf), drifting through the empty voids between the stars, profoundly cold and alone in utter darkness. Recent modelling predicts there could be a lot of them, even to the point they’re outnumbering stars up to 20 times - meaning our own galaxy could be filled with trillions of them.

If your first thought is this…

…then I think we’d get along just fine, if you and I ever met at the pub.

With that in mind - couldn't rogue planets also be regarded as unguided, world-sized ‘spaceships’?

Not entirely daft idea, it seems!

"Simulations have even suggested that some rogue planets might have what it takes to be habitable, either in liquid oceans beneath their icy outer crusts or on the surface if they can sustain a thick hydrogen atmosphere to trap enough heat to sustain life."

And last week, the newly-online Euclid Space Telescope has revealed its first images, each featuring a staggering level of detail. One contains 300,000 (!) never-before-seen objects, some of which are rogue planets that were previously impossible to see by other means.

Added to the recent news that dozens of observed stars seem to be emitting much more energy than they should be, paving the way for extremely fevered speculation about the presence of advanced alien civilizations directly harvesting the energy of stars - well, there’s bucketloads of fuel for your imagination. Crack on, science-fiction writers.

Secondly, you may have been taught at school about Florence Nightingale, pioneering nurse, easer of soldierly suffering, the founder of modern medicine and the ‘lady with a lamp’ during the Crimean War (1853-’56).

But did you know the rest of it?

(How easily the rich complexities of a woman's professional legacy can get smudged away by the history books.)

Okay!

Today, following on from our (repeat) journey along our planet’s longest mountain-chain last week, we’re returning to the poorly-mapped ocean floors covering over two-thirds of our planet - because I don’t want to worry anyone, but it seems there’s something unexpectedly huge under the North Pole.

To set the scene, let’s chase solid land as northwards as it goes.

In the middle of 2021, a group of researchers announced they might have found the world’s most northerly island, off the top of Greenland.

Perhaps that sounds that sounds a bit non-committal? Yes, commendably so! As good scientists always work with hypotheses and theories, they try to remain open to the possibility (however remote) of being proven dead wrong - so it’s a source of ongoing frustration for researchers when their circumspect language is mangled into emphatic certainty, as when the BBC ran this story with the headline “Greenland Island Is World’s Northernmost Island - Scientists.”

(As the text of the article itself made clear, those scientists actually weren’t saying that, because they didn’t have the evidence for it yet. Contrast this with Smithsonian Magazine’s “Scientists Discover What May Be The World’s Northernmost Island.” Much better job of it.)

The unofficial name for this 30 x 60 metre something-or-other is Qeqertaq Avannarleq, which is Greenlandic for “the northernmost island.” From the air, it looks like - and I apologise, but there’s no avoiding it - a huge dollop of s***.

(Call me unromantic, but - imagine you’re out for a walk across a field one bitterly cold winter’s morning, snow and ice crunching deliciously underfoot, and suddenly the way is blocked by a cowpat so substantial you’re wondering if the cow even survived it. That’s what I see here.)

The researchers ended up there by accident - they were planning to take samples from another candidate for the Earth’s most northernmost piece of land, Oodaaq, discover in 1978 and sitting around 780 metres away. In the words of expedition leader Morten Rasch of the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management:

“When I posted photos and the island’s coordinates on social media, a number of American island hunters went crazy and said that it couldn’t be true."

“Island hunters” (nothing to do with the reality TV show) are hobbyists and/or enthusiasts chasing the thrill of being the first to discover new land - so I guess it’s only natural these folk realllly wanted Qeqertaq Avannarleq to be crowned the island at the top of the world.

Yet the research team’s caution was warranted. After continuing to investigate the maybe-island - a complicated job, as the sea around it is permanently covered with a layer of ice up to 3 metres thick - in 2023, they found evidence of water flowing underneath, and no sign that Qeqertaq Avannarleq was physically connected to the sea bed by anything except ice.

However headache-inducingly imprecise the general definition of an island is (like the human invention we call a continent, it’s riddled with infuriating inconsistencies), what we generally seem to agree upon is that naturally occurring islands are made of land, and “land” isn’t the same thing as “ice”. As a rule, if an island is completely surrounded by water or ice, including underneath it, it’s not an island.

Well, except for floating islands! They’re completely different, because, because…uh…?

ANYWAY. LET’S MOVE ON, SHALL WE.

The researchers now agree that Qeqertaq Avannarleq isn’t an island - it’s just an unusually befouled iceberg. At some point, the immense pressure of the surrounding sea ice pressed a particularly big chunk up against a lovely pile of filth (gravel, soil, mud and other detritus, perhaps depositing by landslides) and then that mucky ice slowly tumbled & bobbed its way to the surface.

Not a new thing for this region - these dirty faux-islets appear and disappear all the time - but this time, the hype had clearly got a little too far ahead of the science.

It’s a nice example of how some very human aspects of island research - the urge to be the first to a discovery, the compulsion to find the most extreme examples of them - can turn the whole thing into A Grand Adventure, with all the emotion-driven complications that can lead to.

(Sometimes this can help grab attention to important research - yet if you’re a professional scientist, you’ll already be aware that grant application hacking by turning it into ‘a good story’ is an ongoing problem that can make a mockery of the whole process.)

But here’s something amazing that turned out to be very real - with dramatic consequences for the future of the Arctic as a whole.

This splendidly-adorned chap is Mikhail Lomonosov (1711-1765): Russian polymath, scientist, writer - very much the Isaac Newton of his part of the world.

Amongst other things, he discovered the law of conservation of mass in chemical reactions, he was the first to announce that Venus has an atmosphere, and he founded some of the key principles of modern geology. There's a town named after him in the Petrodvortsovy district of Saint Petersburg, a lunar crater with his name, a Martian crater with his name (that’s just greedy) and even an asteroid too…

And at some point, as legend has it, he predicted there was something MASSIVE under the Arctic ice.

In 1948, a Soviet high-altitude expedition of scientists, pitching a camp on the Arctic ice sea, detected unusually shallow waters stretching northwards of Russia's New Siberian Islands.

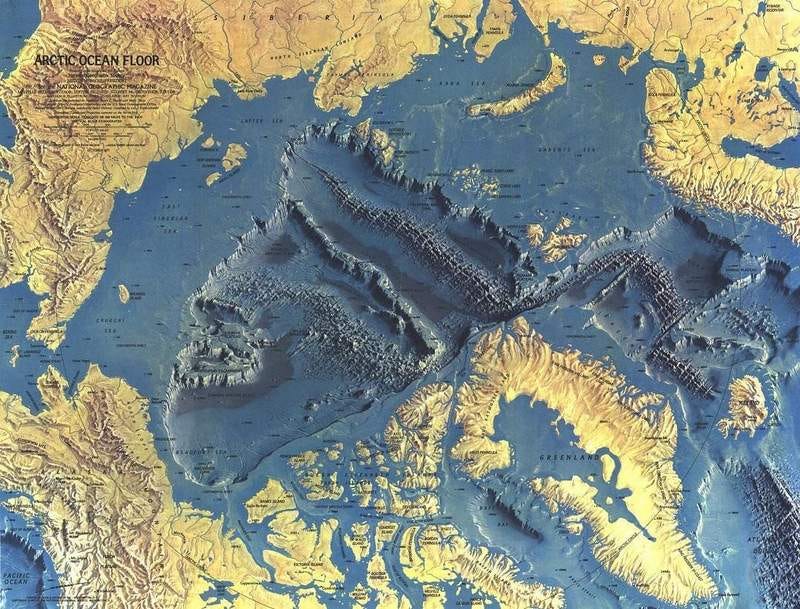

Here's a glorious relief map from the October 1971 edition of National Geographic Magazine (in exactly the same style as the ones modelled from Tharp & Heezen’s data, as I previously mentioned here):

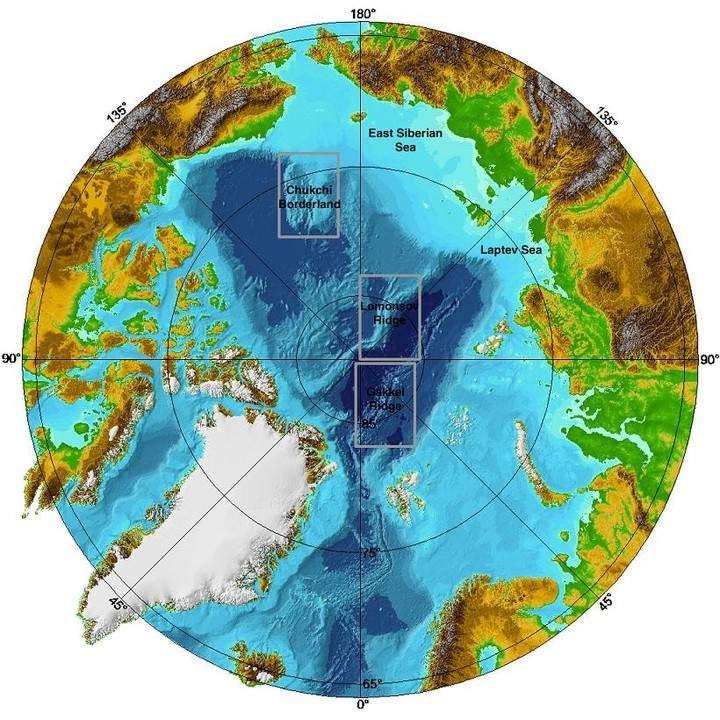

It clearly shows what the Soviet scientists found (with the vertical height exaggerated for clarity). Across the whole of the Arctic Sea basin, flanked by mid-oceanic and volcanic ridges on either side, is a whoppingly huge belt of continental crust.

How huge?

It's more than 1,800 kilometres (1,100 miles) long, and between 3.3km to 3.7km above the surrounding sea floor, for its whole length, getting to within 400 metres of the surface at its highest point.

Imagine a ridge of mountains as high as the Dolomites, with sides almost as steep, stretching from London (UK) to Belgrade (Serbia) or Detroit to Houston - with a flattened top that's between 60 and 200km wide.

On dry land, this would be an absolutely incredible landmark - a standing tidal-wave of rock, dividing whatever continent it ran across. Millions of tourists would come to see it every year. You might have walked along it yourself, or dreamed of owning a little cottage in sight of it.

It's now called the Lomonosov Ridge, in honour of the man who guessed its existence 200 years earlier.

Now the three countries that border on it - Canada, Denmark (via Greenland) and Russia - are determined to lay claim to it.

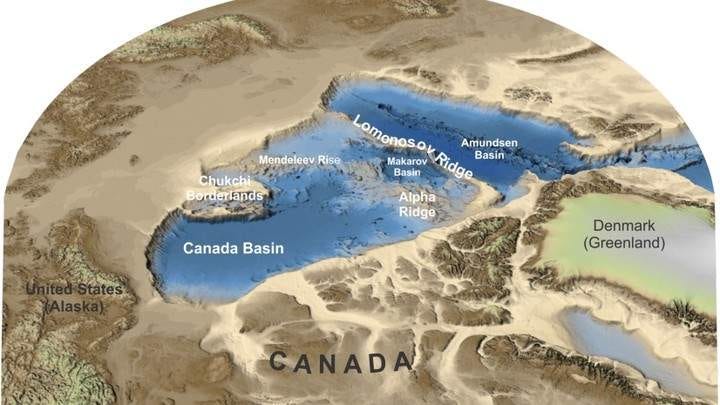

Here is a map (via the Barents Observer) created by Canada as part of one of its claims to the United Nations:

(If you're wondering what the massive, wholly unlabelled continent at the top is, it's called "Russia". Talk about making a statement. 😬)

Each country is claiming it's an extension of their continental shelf, as Martha Henriques explains at BBC Future here:

“As coastal nations, Russia, Denmark and Canada of course already have sovereign rights over the seafloor close to their own shores. Coastal countries can establish an Exclusive Economic Zone that stretches up to 200 nautical miles (370km) from shore, which gives them rights to activities like fishing, building infrastructure and extracting natural resources, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. That law also permits a country to extend its rights over the seabed further – if there are seafloor features that they can prove are an extension of their continental shelves.

For such a seafloor feature to count in a country’s favour, there has to be evidence that it is a piece of submerged land – and not an oceanic ridge that has always been underwater and has little to do with the country’s land mass.

What [geologist Christian] Knudsen’s findings boil down to is evidence that the Lomonosov Ridge is indeed submerged land, and not formed from seafloor spreading, like the mid-Atlantic ridge that runs like a seam from Iceland down towards Antarctica.”

For decades now, its scientists have been working hard to establish the facts, to take to the United Nations to bolster their formal claims.

Extraordinarily, these claims have now become palaeogeological. It's becoming not about where the ridge is today, but where it was, up to millions of years ago.

Imagine laying claim to a place based on its ancient geological history! How messy could THAT get?

(Considering my nearest Scottish island Arran started its geological journey near the South Pole around 540 million years ago, as I previously wrote about here, would that mean Australia or New Zealand could lay claim to it? Or the United States, which Arran’s ancient motherland Laurentia turned into? It quickly gets absurd.)

All this didn't stop Russia sending out an icebreaker & two mini-subs in 2007 to plant a rust-proof titanium flag on the seabed, 4,200m (14,000ft) deep:

Sergei Balyasnikov of the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Institute issued a statement: “It's a very important move for Russia to demonstrate its potential in the Arctic... It's like putting a flag on the Moon.”

Other countries? Less than impressed.

"This isn't the 15th Century," said Canadian Foreign Minister Peter MacKay. "You can't go around the world and just plant flags and say 'We're claiming this territory'."

Quite.

But of course a worrisome question hangs over all this. Is it going to be yet another flashpoint for future global conflicts, considering how all that inaccessible (protective?) polar ice is already melting?

It's true that new seaways will open up, and the Lomonosov Ridge may contain mineral resources - including millions of barrels of oil - which every country would be more than happy to get their hands on (if they exist, which is far from certain).

But this is still, & will be for a long time, one of the harshest & therefore most expensive places for humans and their machines to linger on our planet. Expedition costs currently run upwards of $250k every day. International cooperation is still vital for research to get underway in environmental conditions this arduous.

And of course Russia's geopolitical focus is - shall we say - elsewhere right now.

All this means time. Time for the science, and time for all the right voices to be invited into the room, as Henriques notes:

“As climate change has escalated interest in the central Arctic, the Inuit Circumpolar Council has called for states to engage with Inuit and other indigenous groups and respect their rights. While the central Arctic seafloor might seem to have little to do with climate change (especially if any hydrocarbons there aren’t extracted), being seen to be an environmental “steward” or “protector” in the Arctic is something that Canada, Denmark and even Russia are pushing for.

Indigenous communities are increasingly acknowledged as a crucial part of sustainability, in the Arctic and elsewhere. “Though it’s far into the future, we still have to be mindful of the interconnected nature of the whole ocean and the coastal seas, as well as the potential threats for Inuit and other Arctic indigenous peoples, and the Arctic states,” says Dorough [Dalee Sambo Dorough, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council].

It’s likely to be decades before there is an answer from the UN commission on the science that underpins all three countries’ claims. And it’s possible that the US still may submit a claim in the future, shifting the picture again. Norway, which claimed a more modest extended continental shelf excluding the pole, and with only a sliver of overlap with Denmark, has already had its recommendations from the UN.”

For now, the Arctic sea floor remains the site of one of the hidden wonders of the world, with much to reveal to the scientists of the future.

Let’s hope it remains that place of mystery and of wonder - and of nations remembering their most productive way forward is when they work together.

Images: Annie Spratt; gcaptain; Stefano Bazzoli; CIA World Fact Book/Wikimedia; Alexander Haffeman; GEBCO.

As a Canadian, I've started thinking about what lies under the Arctic ice more and more. At least one ship that is not an icebreaker has made it through the Arctic Ocean from the Atlantic to the Pacific. I don't expect to see it in my lifetime (I'm middle-aged), but major sea lanes across the Arctic Ocean are now imaginable. In other words, the old dream of the Northwest Passage is about to come true. And what commodities might be under the ocean floor? I can only hope that our leaders are making long-term, strategic defence plans for our northern frontier...

I thought that the "something incredible" under the pole was going to turn out to be the remants of one of the rogue planets that this edition opened with, deeply embedded in the Earth.