Now We Are 30,000: More Clueless But Well-Meant Advice For Writers, Artists And Fellow Idiots

Blimey blimey blimey.

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science and wonder and the timeless wisdom of not eating plutonium and other ridiculousness.

Today’s edition is a very special one.

(And it’s also a spectacularly long one - so you will need to click through to the Web version if you’re reading this in your email provider’s Inbox, because it’ll be cut off somewhere below.)

First, a true story.

When I was an archaeology student working in Orkney, I once climbed a hill and found an old man at the top of it.

He was sat outside his spectacularly ramshackle bungalow on a rain-warped and slightly charred wooden chair, with a dog at his feet. His eyebrows took up most of his face.

He pointed one fascinatingly wizened finger at me.

“You! Inside and hae tea with me,” he commanded in a voice that could have ordered armies over cliffs.

At we sat in his ramshackle living room, me sipping tea from a well-chipped mug, him eyeing me beadily, he gestured to the window.

“Y’see all that? I owned half of it. It was mine. MINE. Ah. But then I had to give half away. Ach, I dinnae want to talk about it.”

At first I was confused. How do you give away half a window? But then I realised he meant the view, where the full extent of a neighbouring island could be seen.

“It was mine. Bastards. Ah well. Are you enjoying your tea now?”

Shortly afterwards, the gentleman’s daughter burst through the door festooned with bulging bags of shopping, saw me sitting there, said something like Oh hello, oh dear, I see he’s done this again, I’m sorry, you’re not the first, explained that her father was very tired and needed his nap, and gently shooed me out the door - and that was the end of my visit. I never saw any of them again.

I’ve never been able to find out if he really did own half that island, which is now under community ownership. It’s quite possible - or it may be utter bollocks, of the kind that makes a fun anecdote & very little else.

I would now like to suggest that a lot of internet creative business advice should fall under this category - and yet rarely does.

Of course we loudly online folk will always present an edited and curated view of our apparent success, in a performative way that’s artfully used to drive even more attention to our efforts. This will happen whether we mean it to or not, because we’re people, doing what people tend to do.

That doesn’t mean you should automatically ignore us - but you should take everything we say with a pinch, a teaspoon or even a dumper-truck full of salt until you’ve actually tried it out for yourself.

So! Before we begin this newsletter, I’d like you to do something that will help you treat the advice in this newsletter with the appropriate lack of respect. It’ll only take you a few seconds, and it’s really important.

Ready?

Please do the following:

Stop reading.

Scroll down to the comments section and click on it (if you’re reading in email, this will take you to the Web version.)

Start a new comment.

Write “Hi Mike! You’re still an idiot.”

Click the orange “Post” button to publish that comment.

Come back up here and carry on reading. (You can always go back later and edit that comment if there’s anything else you want to add.)

If this sounds like pointless masochism, far from it! This is actually highly useful masochism, and it helps both of us in the following ways:

It’ll remind us that despite the more pompously self-congratulatory aspects of the rest of this newsletter, I am in fact Just Some Random Bloke™ who is making it up as he’s going along - so you should never, ever take my advice without testing my advice.

Also, you’d be doing me a delightful favour. I’d find it endlessly hilarious to read hundreds or even thousands of comments calling me an idiot! I know this because many of you did it here, and it tickled me for weeks.

(If you’re not British, you might have an entirely different reaction to all this, such as ruminating worriedly over my current state of mind, but trust me - it would feel like Christmas and my birthday have arrived on the same day.)

OK. Done that?

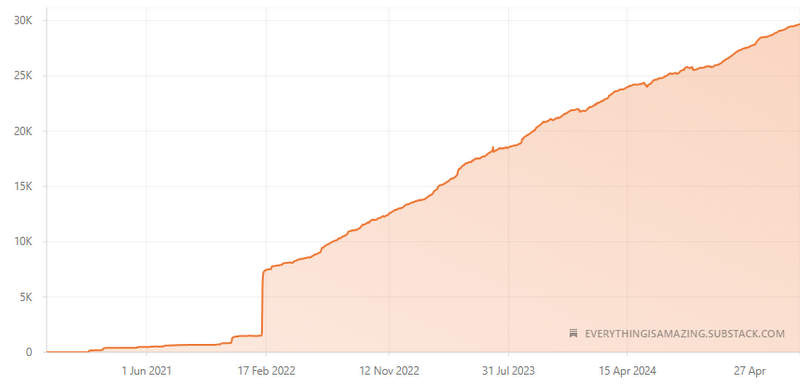

Thank you! Now we can tackle the rest of this newsletter, which is a response to the following graph in my Substack Dashboard:

Somehow, there is now one-third of a Wembley Stadium of you reading Everything Is Amazing.

Gosh.

The other times I have hit milestones like these, I’ve taken the opportunity to ramble out my best advice for writing online, growing a newsletter and getting your work noticed on an increasingly noisy Internet.

Click below to read those posts.

Now the urge is upon me once again - so here are three further tips, with a reader-crowdsourced Q&A at the end.

1. We Are Here To Selectively Wow People.

A common mistake many beginners make when writing a newsletter or blog is the understandable temptation to try to cover everything.

This is just so easy. Say you want to write about a thing, so…

you draft up a bullet-pointed list of parts of that thing…

you go to a source like Wikipedia to get a broad outline of the thing, or plunder a few books or magazine articles to research the basics…

you then leap off into all sorts of detailed primary well-referenced sources to shore up your research…

…and then you try to write the whole thing up by boiling down everything into some absolutely whoppingly endless piece of work consuming acres of screen-scrolling that would take readers hours to properly pick their way through.

Only thing is…

Are you really trying to be as reliable and authoritative as all that first-hand research when you’re not actually doing any of that research yourself?

Are you trying to be as comprehensive as Wikipedia?

Are you trying to become the number one source of facts on this topic in the whole world?

Whew, because that is really bloody hard to do. Best of luck! You’re going to need it.

Unless you’re unusually ambitious and have a real flair for summarising things in an unusually entertaining way, all this is a great recipe for burnout. But far worse, it forces you to become all plot and no character in your haste to cover everything, occupying a 40,000-foot perspective on the topic without ever coming down to ground level to tell those intimate tales that will really bring the subject alive for your readers.

In other words, it stops you telling stories.

One alternative is to take a limited-series approach. You don’t try to cover it all. You cherry-pick what seems most interesting, and you zoom in on stories that go a long way towards giving a flavour of the whole topic, but can also be enjoyed in a standalone way.

This is the approach I take with Everything Is Amazing, where every season has its main theme and I’m presenting myself as an interested enthusiast taking his first wobbly steps into learning something about it.

For example: could I, say, spend a season covering the vast expanse of modern oceanography and not boring the pants off my readers? Not a hope. But could I make a few workably entertaining stories about the lost-to-the-sea ancient landscape of Doggerland, or the underwater mountain range that runs for 65,000 kilometres, or why living under the sea is so damn tricky? Maybe so!

But there’s another side to this, and it applies to all forms of writing.

If you fall into the Wikipedia trap, you’re also at risk of forgetting how human beings actually remember things (a topic I wrote about last season for paid subscribers). What most often sticks isn’t “facts” - it’s the way those facts are reinforced and woven into a tale that makes us feel something.

Fact is, a lot of Wikipedia is well written. It’s not just a planet-sized almanac of raw data, because then it would be impossible to “read”, in the same way a phone-book used to be.

(For anyone under the age of 25: once upon a time, everyone’s name and address and phone number was listed in a really big book that was physically mailed out to everyone - for free! I promise I am not making this up.)

In a widely-shared essay in Prospect Magazine, Cal Flyn (author of the utterly fascinating Islands Of Abandonment) talked about the great challenge of writing in a way that lingers in the memory and inspires real action:

“A quotation, commonly attributed to the writer and pioneering French aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, says: “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” This, if I ever read one, is a manifesto for nature writing in the present day. This is our own task: to evoke the experience of being in this wild and beautiful world. To stir people to love the planet with a jealous passion, to act in a way more befitting of a custodian or even lover. Go in through the heart, and the head will follow…

We need to be roused. We need to feel. We need a siren song that lures unsuspecting souls to the cause: a song to enchant us, to put us to work.”

This is what the best stories do - including non-fiction ones. They’re not just trying to stuff our brains with dates and data. They’re also trying to tug at our emotions (the real power behind our ability to make decisions), to make us feel something so intensely that we can’t just shrug it off as we watch, read or listen our way onwards into an infinity of available information…

In short: good, intimate storytelling helps stir your readers up, in the hope they’ll do something with what you teach them.

Forget this at your peril.

2. Goals Suck. Try Experiments Instead.

I used to think goals were a sensible way to organise your creative work: decide what you want to make, decide how you’re going to make it, and then apply yourself in an inspiringly dedicated way for as long as it takes.

Now I think…well, this sometimes works. If you’re writing a book, for example, and you’re at the point where you absolutely know for sure what you’re writing, then it’s a matter of hitting a decent word-count every day until the damn thing is done.

The problem here is that I haven’t yet written a book (I intend to amend that this year). And if you talk to people who have written books, you may find they’ll tell you it’s nowhere near that simple. In some cases, drafting the book is how you discover it’s not (yet) the book you want to write, and so, metaphorically speaking, your ladder is currently propped against the wrong wall, so you’d be a fool to keep climbing it.

So, back you go to try to unravel and reknit it anew, armed with everything you’ve learned from doing it a bit (or a lot) ‘badly’.

This is a long way from a lot of goal-driven advice out there, which relies on applied certainty: make a plan - make it happen - change the world. In reality, the world usually fights back, and you rapidly become a different person along the way, rendering you an imposter in your own creative journey.

So what’s the answer?

Feeling like Homer Simpson up there is where a lot of goal-oriented thinking can land you.

At least, that’s been true in my case. I’d go through countless cycles of setting ambitious goals, making a start on joining up Here to So Damn Far Over There, and at some point flaming out in a sputter of disappointment because life got in the way.

This is the problem of a goal, of course: it requires absolutely unassailable advance planning. It says “I will create a plan that reality will dash itself to pieces on, and *I* will be the one to determine the future over the next x months/years while I make this happen.”

And then the world says LOL and punches you in all the places that hurt.

And then, halfway along, you realise you actually want something a bit different from life, and that goal doesn’t quite fit you anymore - and as that process continues and your true desires diverge from your imaginary path, you become more and more confused and self-doubting. Is this really what I want? It isn’t. Dammit.

As I said with my First Law Of Curiosity, we usually attempt “useful” things because we’ve already decided what we want to get out of them.

Goals are exactly the same.

We’re claiming we know the value of them in advance of the journey we’ll take to achieve them - a journey which will change us profoundly, during which our world will also change profoundly.

(None of this takes into account what you might learn along the way, including the things you’ve never known you didn’t know.)

So - goals suck. Or at least, they’re frequently woefully unrealistic.

What’s the alternative? Surely we need something to point ourselves at?

In my case, since I started this newsletter, I’ve been a big fan of experiments: cook up an idea that feels worth testing, give it a go, see what happens, iterate accordingly (if it felt good/fun and people cared, evolve the idea further; if it was boring and ineffective and nobody gave a toss, then hurl it away like a hot potato).

All these experiments have a general direction to them, based on things I’d love to end up doing at some point, but beyond that - well, I’m mostly just finding out what happens, and reacting accordingly.

In this, I am doing nothing original. Countless writers and business owners have retooled what they’re doing in such a way! Old as the hills, this.

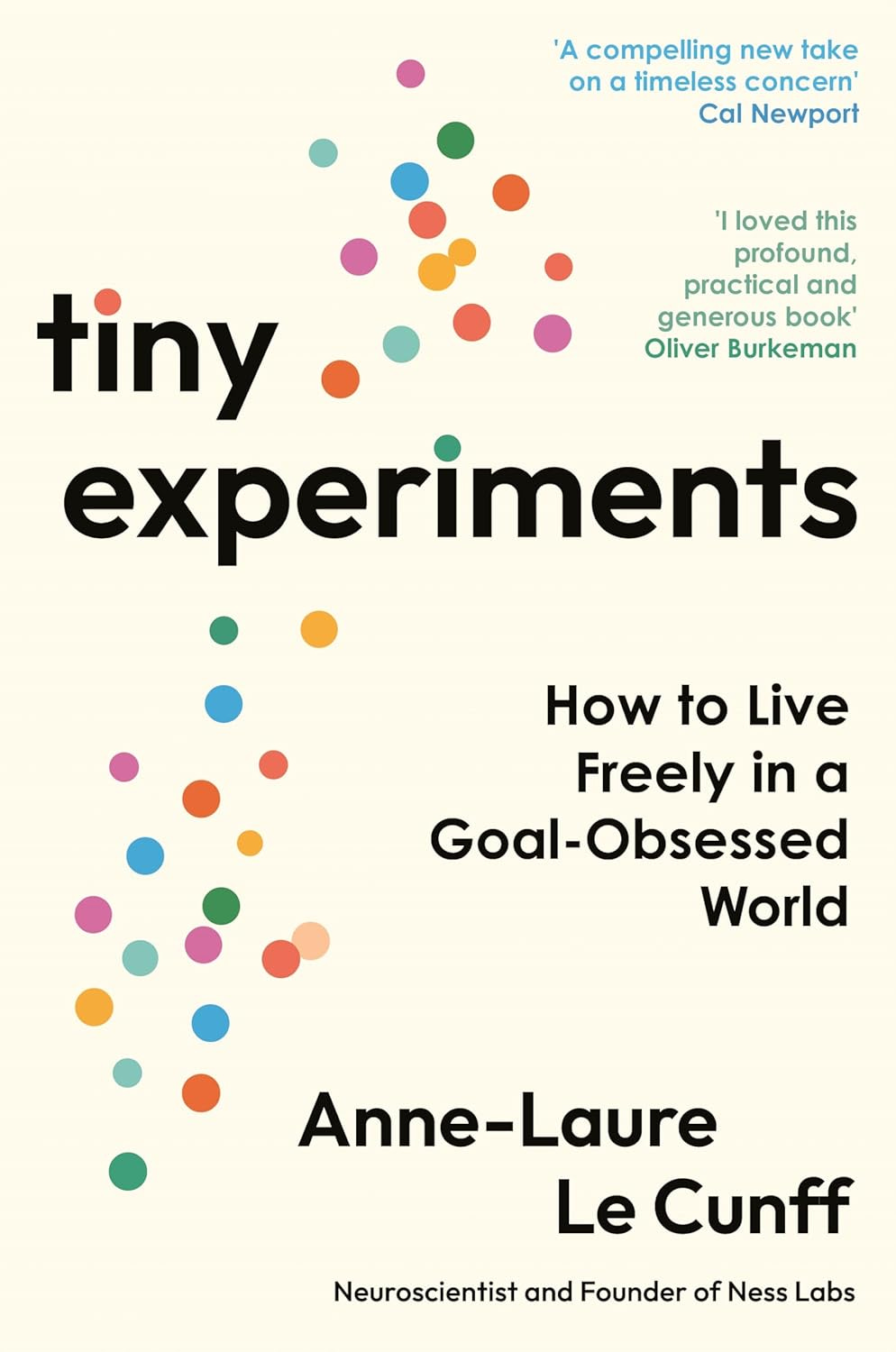

But it was certainly encouraging to read this absolutely terrific book (hat-tip to my friend Rand) and learn that an experiment-driven approach might be the smartest way to do things:

You can grab a copy of it here. I reckon it might help.

(There’s also a deeper philosophical point to consider, and it’s this: a life of strategic experimentation is sensible because EVERYTHING in our lives is fundamentally uncertain, and only death is truly inevitable. But since that’s a terrifying note to end on, let’s pretend I never said it. Lalalalala, here is a highly distracting punnet of kittens, etc.)

3. You Can’t Talk To Enough People

This is a two-parter.

1) Reporting In

Because of the current turmoil in US politics, Substack is having something of a moment (and I’m sure the same is happening at Ghost, beehiiv and all Substack’s competitors).

Every day, a famous news anchor, political commentator or politician is opening a newsletter and setting up shop - including former Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, former Washington Post cartoonist Ann Telnaes, and, just a few days ago, lawyer and former MSNBC host Katie Phang.

These folk are quickly racking up hundreds of thousands of subscribers - making a few Substack newsletter writers feel like their efforts are in danger of being swamped by the presence of those celebrities.

(My own take on this: we can all benefit, because once those audiences have devoured that famous person’s stuff, a percentage will curiously wander outwards in our general direction, thinking “hey, what else is in this neighbourhood?”, hastened along by shout-outs, Recommendations and links on thoughtful comments.)

However you feel about the arrival of these veterans of the news industry, one thing is certain: they really know what they’re doing. They have journalistic skills and instincts you only learn from working really hard under intense pressure for years…

And one of those skills is reporting.

When I was a travel writer, I learned that one tell-tale sign of inexperience was a lack of quotes. If you’re diligent enough to be making notes properly, you’ll be writing down what people actually say to you, instead of being forced to paraphrase them later from your imperfect memory - which is such a nerve-wracking thing (“oh god, what if they read it and complain that they never said that?!?!”) that it usually feels safer to omit dialogue completely.

If the same is true for writing a newsletter, then veteran journalists are now here to teach us how it’s done.

The best of them know how to ask piercing questions that cut to the heart of things, and they know how to leave enough space to allow for a proper reply - and they know how to really, really listen.

If you’re writing any kind of non-fiction, including the kind of second-hand science writing I specialise in, your work can be immeasurably improved by talking to the right people when you’re throwing a story together.

It’s also, dare I say, fun.

Just read

, who throws herself onto the streets of New York every week in search of the surprising, the lovely and the utterly absurd:As far as I can tell, she’s more or less unique in how she assembles her newsletter. It’s street-level reportage with a gonzo twist. In the words of

: “A former Wall Street Journal columnist traipses around NYC interviewing random senior citizens and investigating weird trash piles... what's not to love?”And there you have it: she’s a former newspaper reporter. She learned to go out and find stories by wearing down shoe-leather and talking to people - and it really shows. (If Anne ever assembled a course on how to interview people, I’d be the first to buy it.)

These are skills we homegrown newsletter writers could really benefit from.

Time we got learning them.

2) Geeking Out

In his 2010 book Where Good Ideas Come From, science author Steven Johnson explains how our….

Oh, wait, I don’t need to do this. There’s a mesmerising 4-minute video with Johnson’s voice explaining his core argument, while someone with immense artistic talent hyperactively sketches the whole thing.

Please watch it. It’s absolutely dazzling:

Done that? Grand.

Johnson’s perspective is environmental - a little like how Annie Murphy Paul’s recent book The Extended Mind lays out an argument for regarding your surroundings as a cognitive aid, a “mind outside your brain”. If you have the incomplete makings of a good idea, you need to surround yourself with other people, in the hope their half-baked notions might collide with yours and complete them in a way neither of you saw coming.

(This can sound a bit parasitical - so, hey, always give credit, when you’re aware of whose thinking has influenced you! It usually requires so little effort, and it can have a huge effect on the other person, especially if they’re feeling like their work is about howling into the void - we’ve all been there. And if it’s a great idea you intend to make money from, maybe they could get a cut of it?)

As I said recently, I’m currently face-chatting with a couple of strangers a day over Zoom (a thing originally pioneered by my friend

):It’s the third time I’ve done a block of calls like this, and now I’m a few dozen calls in, and it’s proving just as fun this time round.

In an ideal fantasy-world where constraints of time, space and money didn’t apply, I’d set up free half-hour calls with every reader of my newsletter.

That would be amazing, and I would learn so much!

Alas: 30 multiplied by 30,000 is 900,000 minutes, meaning I’d be at it for around 625 days, doing nothing but drinking coffee and talking to people. Not exactly practical or medically advised. (If this newsletter ever goes silent for more than 18 months, maybe that’s the reason and I’m doing it for a bet.)

Instead, I’m doing what I can. I’ll open these calls to free readers of Everything Is Amazing once in a while, and paid subscribers can contact me anytime so we can arrange for a chat when it’s mutually convenient.

My reasons for doing this are mostly selfish. Not only do I find it fun, it also helps me write.

If I wrote this thing out of the narrow confines of my own brain, it would be considerably dumber.

I have readers who are true, widely recognised authorities in some of the things I write about (this keeps me up some nights) and any time they leave a note in the comments to correct me when I’ve unhelpfully mangled my explanation of something, they’re generously giving me an incredible gift. I should be grateful, and I absolutely am, and none of this would happen if I was just on broadcast mode, blah blah blah here are my opinions and I don’t care what yours are.

The same is also true for previous versions of myself - or, to put it more coherently, the things I’ve previously written about. Over the last 4 years I’ve changed as a thinker and writer, and if I pretend to myself that either (a) my earlier stuff was rubbish or perfectly correct and (b) it’s “dead” because it’s published and gone, then I’m forgetting the power of running a blog-like newsletter.

(If you’ve been writing for a while, here’s a valuable tip: grit your teeth and grab a bottle of wine and go back to read all your earlier stuff. It’ll be painful. You may even need another bottle. But you’ll also discover that your earlier work is an asset. You can bring it back into the daylight, rethink your way through it, improve it, republish it, even finish it in a way you never could because you weren’t yet the You that you now are!)

Okay, I could labour this point for another 5,000 words. Instead, here’s the gist: you need more conversations around your work. Meetings with fellow artists at the digital watercooler. Random, “pointless” chats with people who enjoy your work (or maybe even hate it!). More time rediscovering your earlier work, sifting through that vile muck for a glitter of gold. All of these things.

Open a dialogue with your wider universe, and it will speak back to you and tell you things you’d never have guessed on your own.

Best of luck!

Reader’s Questions (via Substack Notes)

asked: “My question is how you ended up here from being an archaeologist (hopefully I have that right)? Not a searching question and not calling for any revelations, but I thought it might be interesting. I’m not sure anyone really knows how they end up where they are – I don’t for sure.”

You have that right! And the answer’s pretty simple: I wasn’t a terribly good one, so I didn’t stay working as one for very long!

But I do not regret taking a BSc in Archaeology in any way, because it taught me how to think - same way that travel writing (which I was only fair-to-middling at) taught me how to write. Both of these professions furnished me with the curiosity, temperament and skills I needed to get this newsletter off the ground.

For a more detailed back-story, check out the interview I did with here:

asked: “Do you find that having that number of subscribers changes what you write? Do you self censor/second guess etc?”

Excellent question!

Hmm - maybe? I’m not sure.

I do know that I tend to avoid plenty of controversial topics in here - but that’s usually because I know too little about them, and I’d want to have my thinking straight before launching into a “debate” (read: argument) with someone who vehemently disagrees with me about those things.

But do I avoid those topics because I’m scared of that happening? I don’t…think so? (But possibly that’s a lie I tell myself.)

What I always want to do, though, is to encourage everyone to second-guess me alongside me. I am a student of much (okay, of everything) I write about in Everything Is Amazing, and I am bound to get some things wrong, or at least word them in an unhelpfully clumsy way.

I am not afraid of that process because it makes my work better - but I’m also human, so of course it makes me cringe a bit when I drop an absolute clunker and have to follow up with a mea culpa. Such is being human. We get stuff wrong.

I hope all of the above remains true as this newsletter (hopefully!) continues to grow. If it doesn’t, everyone please yell at me. Thanks.

asked: “Maybe put in a few word on why a little kindness goes a long way!”

Certainly!

It’s good to be kind.

But it’s also easy to be kind when people are being nice. It’s important to do it (because they deserve that kindness), but it’s also the low bar.

If you really want to test your kindness skills, be kind to people who are acting like total jerks. That’s when you’re really stretching yourself - and, maybe, just maybe, that’s when some kindness is desperately needed.

Also, Block early and often. There’s no contradiction in being kind *and* refusing to engage with noisy idiots who clearly just want to steal your emotional bandwidth.

I also previously wrote a bit about kindness here:

asked: “As a brand new writer here with a dozen subscribers, I'd love to hear about what your trajectory looked like in terms of finding people to read your work (and sometimes even pay for it!”

That’s a big question to answer! But regarding finding people, aka. marketing, the two things that have worked best for me have been using social media and writing in seasons.

I wrote about using seasons here, under “Add a bit of Seasoning”..

And I talked to Substack here about how I used Twitter to tell short, wow-infused versions of some of my stories to drive free signups. (I’m now doing the same on Threads and Bluesky.)

Hope that helps!

asked: “Tell me the last secret of Fátima please.”

Here it is:

If you want to get a man to do a household chore, ask him to explain it to you.

Of course, I never said this. And I was never here. Peace be upon you.

FINAL WORD

If you think the last 4,500 words were not a complete waste of your time, you may not be entirely put off by what I have behind this newsletter’s paywall.

Last season I wrote a paid-only series about the latest exciting research into human memory.

And the season before that, another series about the surprising ways ancient geology affects our modern lives.

I also have standalone pieces on how we can “see” the world like Daredevil, that time lots of Americans thought there were goats on the Moon, the geological ‘superblob’ powering Hawaii and other global hotspots, the science of keeping going when things are tough, and all sorts of other stuff.

By upgrading to a paid subscription, you’d be able to access the extra 20% just for paid supporters of this project, and you’d also be helping this thing survive and grow.

I’d love to welcome you aboard - and there’s even a discount running at the moment.

Up for it?

Thanks for reading!

- Mike

Images: RDNE Stock Project; Alex Alvarez; Ana Municio;

This was a genius move to increase engagement. Clearly you are not an idiot, but an evil genius.

Hi Mike! You’re still an idiot.