Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, attention, wonder and strange things under the Arctic.

First, a fun update to this story I did a while back on the ‘Stargate’ portals between Lithuania and Poland:

You may have heard that New York and Dublin recently got their own portal connection - and here’s gonzo reporter

(of “SKWON!” fame) checking it out & somehow managing to bump into its inventor, Benediktas Gylys:"Sometimes I want to stay in the shadows," he said. "It requires a lot of energy to talk to multiple people. Some days I just feel like talking, so I step into the conversations people are having, to see if they have questions. And that's how they discover I'm the creator. And sometimes I pretend I know nothing about the Portal and just start spreading my theories—my urban legends about the Portal."

(Anne writes such a great newsletter. Also such a mad newsletter! This is an endorsement, Anne, I promise.)

Okay! To business.

Today, let’s visit the guttered ruin of my teenage years, in search of someone to blame.

Buckle up please. The suspension in this thing is terrible.

It’s the mid-1980s, and I’m being driven to school.

“No, Ma, you can just drop me here. It’s fine.”

“Don’t be silly. It’s only a hundred yards further…”

“No, here would be great. Or maybe you could just kill me instead?”

I don’t say that last bit out loud, but it certainly feels like an option I’d consider. Just push me out the car and back it over me, Ma. Or I could wrestle the wheel from you, and at the age of 14 I’d learn how to drive just enough to get us the half-mile to the sea where, shrieking in outrage at the tragedy of my curtailed existence, I’d steer us into the waves and that’d be an end to it.

Literally anything but you continuing to drive me to the school gates in this bloody thing, Ma. Please? Please.

“There you go, love. And look! All your friends are waiting for you.”

They’re not my friends. They might have been one day if I’d done nothing weird, nothing freakish that indelibly marked me as Other. But since my mother started driving me to school in her Reliant Robin, my destiny seems writ.

Do real friends point at you and howl with laughter, Ma?

Do they make the “you’re a wanker” hand-gesture in the way they’re all doing right now? Is that a sign I’m destined for school-yard greatness in years to come?

I’m not feeling it, Ma. That’s not what is happening.

She pushes me out, gives me a kiss on the cheek and then drives away, leaving me to my fate.

As it wobbles down the road, the three-wheeled septic tank car’s exhaust splutters and bangs. She got it for a few hundred quid a year ago, and it’s never run right. One time on the long straight to nearby Bridlington, a huge gust of cross-wind flipped it into the verge, and my dad had to go out in his Actual Car to drag it out. It’s broken down a few times, and it occasionally farts out a clot of Mordor-black smoke as if something infernal lurks in the engine.

I’m at that age where you take everything personally, so I’ve taken all this personally. It’s my first year at high school (“secondary school” in UK vernacular) and I’m desperate to make the friends I failed to make in the nearby primary school the previous year.

I feel like this is a chance at a fresh start, a last-ditch reboot of my brand image. The remainder of my school years rest on this. I cannot mess this up.

So naturally my mother buys Britain’s most famously shitty car and drives me everywhere in it.

That’s not what I remember best, though, these forty years later. The embarrassment has dulled, as embarrassments tend to do. The force with which I cringe at the memory no longer propels my spectacles off my face. I have, to a certain extent, forgiven my mother for her well-meaning carpet bombing of my reputation. Time has filed the edges off these things until they’re merely unbearable.

Instead, what’s brightest in my mind’s eye is how I felt that very first time we rolled up to the school gates, when I had no idea how endlessly un-cool Reliant Robins were. I knew nothing of cars, and I’d spent all my time reading books and playing videogames, not watching TV. I knew what Only Fools And Horses was, but I’d never actually seen it. I didn’t know what a national joke Del Boy’s car was considered to be.

Instead, I remember thinking, with excited pride and startling accuracy: oh wow, I bet nobody else’s parents have a car like this!

According to folk who study it, we change our opinions in two broad ways as we stumble our way through the overwhelming data-deluge of the world around us.

The first is called informational social influence: you read the facts of a thing (hopefully in a credible publication that cites and checks other reliable sources) or you hear the facts of a thing from someone you trust, and your opinion shifts in a new direction.

Without this form of thinking, I wouldn’t have a newsletter - I’m never an expert about anything I write about, and I’m always delighted if someone corrects me with something I never knew. Please bring it on, if you have the facts to back it up!

The second is normative social influence - and it’s why I learned to hate Reliant Robins. You learn that a social group you want to be part of is holding a certain opinion on something, and your thoughts self-servingly drift in the direction of agreement with it. It’s pretty well understood how this can be a bad thing: groupthink kills creativity, staying in your ‘bubble’ stunts your worldliness and your critical thinking, and so on.

(We probably all do it to some degree, and now that I’m writing for a bigger audience than at any time in my career, I’m permanently fearful of losing the self-awareness that I’m no different.)

The online world runs on strong opinions. A lot of this might just be basic biology: our brains are cognitive misers, preferring to spend the least amount of energy they can get away with. The quickest and easiest way to think is what cognitive scientist Daniel Kahneman called “System 1 thinking”, relying on our emotional intuition, our hunches and the automatic thinking we do when we tie our shoelaces or recognise something is far away because it’s parallaxing behind a nearer object: unconsciously-performed, stereotypical, and really, really quick. System 1 thinking powers a lot of our opinion-making - and its lack of considered analysis can get things dreadfully wrong.

Maybe you saw the recent viral story of Corey Harris, a man from Michigan who Zoom-called into a court hearing about his suspended license while driving a car, to the utter amazement of the judge presiding. It was everywhere on social media, usually shared with accompanying comments like “LOL” and “there is no word for being this stupid” and so on.

And then the follow-up details arrived: it looked like he assumed his license was still active, and it was the court’s fault in bungling the paperwork (hat-tip to Brendan Leonard for this).

But now, a further twist: it seems he never had a driving license in the first place.

Of course this kind of stuff is viral gold for social media. Every new update adds more and more to the story, perfect fodder for newspapers - and triggers another round of blaming, shaming and mud-slinging cruelty within the discussions around it (although what gets amplified the most is the original story, because that’s the one with the most power to go viral, for all the wrong reasons).

As Brendan says, it’s impossible to unring any of these bells - once shared, never forgotten, and it’s easy to conclude it’s more proof people are awful and the world is ruined. Yay for negative media cycles.

I could bang on about the toxic uselessness of this story in any way except as recreational mockery (ugh) or as a reminder that ridiculing strangers isn’t great behaviour. I mean, that’s certainly a thing.

And then, because the language of television memes is far more appealing than anything I could ramble at you, I’d point you towards the best scene in Ted Lasso:

Everyone knows being judgmental is bad. No question there. But wait - how about being opinionated?

Having a strong opinion is enormously attention-grabbing. Aren’t we all drawn towards folk who have the confidence to speak their mind without any hesitation, ambiguity, obfuscation or equivocation (and who use much shorter words than any of those)? Isn’t that the essence of a sound-bite that travels far: punchy, succinct and so very damn sure of itself?

However this fad for performative certainty began - and I’d start by looking at the influence of Dale ‘Extroverts Always Win Big!’ Carnegie, for all the reasons that

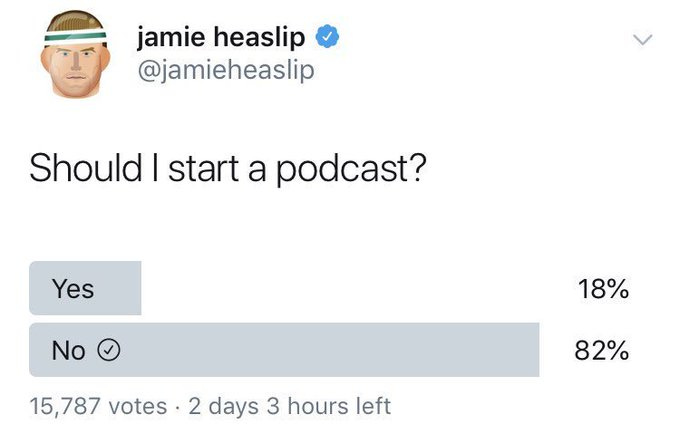

laid out in her book Quiet - it seems this is still a model of expression that gets most of the attention, helped along by the character-limits of social media platforms. If you’re just someone who prefers to expand arguments and ask a lot of questions, well, you’re not going to look anywhere near as interesting.Don’t get me wrong - asking questions can be an absolute minefield. Just ask this Irish rugby-player:

But on the whole, questions are a virtue (if a privilege). They feed your curiosity, that inner impulse-drive that eventually should carry you to a place of greater wisdom - but having already “made your mind up” starves curiosity dead. Why would you re-break what’s already been fixed? Your energy-thrifty and constantly overwhelmed mind hasn’t the heart or the time for it. Job done, life short, move along please, lalala not listening.

Here’s organizational psychologist

on why this is so problematic, from his book Think Again:“A few years ago, I argued in my book Originals that if we want to fight groupthink, it helps to have “strong opinions, weakly held.” Since then I’ve changed my mind - I now believe that it’s a mistake.

If we hold an opinion weakly, expressing it strongly can backfire. Communicating it with some uncertainty signals confident humility, invites curiosity, and leads to a more nuanced discussion. Research shows that in courtrooms, expert witnesses and deliberating jurors are more credible and more persuasive when they express moderate confidence, rather than high or low confidence. And these principles aren’t limited to debates - they apply in a wide range of situations where we’re advocating for our beliefs or even for ourselves.”

(But what about the Flat Earthers and the Anti-5G tinfoil-hat-wearers and the like? Aren’t they also “asking questions” by rejecting the scientific consensus? Well, no - they’re not presenting themselves as uncertain. It’s definitely all a conspiracy, and they’re using questions to try to catch out those evil, corrupt scientists. Their actual opinions are like diamond zircon.)

So here’s a suggestion that would prove deeply unpopular if I put it on social media, so I’m going to share it with you instead:

We don’t have to have an opinion on everything.

My personal stake in this is that I’ve arrived at the advanced age of 52 years old being uncertain about almost everything, sometimes radically so.

There are certainly things I want to believe are true: that the scientific method (Kahneman’s “System 2 thinking”) is more reliable for thinking about stuff, that there’s an essential decency in most of us (even when we’re acting our most idiotic), that kindness can create understanding across seemingly unbridgeable divides in the way Mónica Guzmán demonstrates here, that The Expanse will eventually come back for a seventh season, that humanity will always muddle through, that the best way to pronounce “scone” is of course “scone”, and so on.

I have a deep interest in learning the facts and apprehending breaking news about these things - and maybe, over time, new evidence will show me I’m on the right track? I hope so.

But other stuff? I really don’t have a clue, and I’ll tell you as much if you ask me. I therefore don’t have an opinion on them. Sorry!

I’m not giving you a list of what those things are. Let’s just say you’d be amazed I’ve survived into my fifties.

But one of them - is driving. I’ve never learned to drive, to the utter incredulity of every American and Canadian I’ve ever talked to about this. How is this possible, Mike? How did you achieve this? Oh, you know, I just gritted my teeth & read sci-fi novels and played videogames until I was rendered unemployable in any normal way, then I became a writer! Easy-peasy. Anyone could do it!

But as an alternative to many other far more sensible and useful areas of personal knowledge that I could have expanded over the last 40 years, here are some things I’ve learned about my mother’s Reliant Robin since the time she destroyed my mid-teens with it.

Firstly, my greatest fear of them was what happened when they ran you over. It’s never happened, but I’ve always assumed that if a car was going to run me over, I could throw myself to the ground and lay very flat and straight indeed so that the car passed overhead and both sets of tires passed on either side of me. (I think I got this idea from the truck scene in Raiders Of The Lost Ark.)

However, the Reliant Robin has a single front wheel that’s right in the damn middle. No escape, and a muddy tyre-track right up your face. That’s not a dignified way to go.

However, after meeting an owner of a Robin a few decades back and asking him to very, very carefully run over one of my steel-toecapped boots, I’m now pretty sure I would do the car more damage if it ran into me than vice-versa. They have a certain structural bounciness to them…well, I’m not going to test it properly, but I no longer wake up in a cold sweat.

Secondly, they’re a lot harder to tip over than most people think. This myth is mostly down to the following sequence from Top Gear:

Jeremy Clarkson, the morally bankrupt wretch, has since admitted that the TV show’s engineers tinkered with the car so he could deliberately roll it on every steep turn, while also confessing how unfair he thinks this is:

“It makes me sad, if I’m honest, because rolling a Reliant Robin on purpose is a bit like putting a tortoise on its back. It’s an act of wanton cruelty. When you see it lying there with its three little wheels whizzing round helplessly, you are compelled to rush over and put it the right way up.”

Thirdly, you can legally drive them on a British B1 Driving License (“light vehicles and quadricycles”), which in the 1980s cost significantly less to purchase. Adding on the dirt-cheap price of the cars themselves (probably because when Only Fools And Horses started airing everyone suddenly wanted rid of them), and it’s clear my mum had herself a bargain. Not a fashionable one, certainly, but an admirably thrifty one.

(Maybe I ate a few extra meals because of that car. Eeee. Times were hard, but we got by.)

Does any of this change my opinion of Reliant Robins? Not much. Various muscles around my eyes still twitch if I see one out in the wild. If I saw someone’s kid being driven to school in one here in Scotland, I’d probably cause a scene (“GET OUT WHILE YOU CAN, ANGUS, SHE DOESN’T KNOW WHAT’S GOOD FOR YOU”). That damage is clearly done. I’ll never be that naive & hopeful kid again.

But anything that you haven’t formed an opinion on yet - have you thought of, you know, just not doing so? Not deciding? Just sitting with it, to allow you to keep thinking about it?

To quote one of my favourite writers on Substack:

“The discourse demands that you pick a side. That you choose your weapon and decide. I haven’t made my mind up and I won’t make a choice solely out of deference to other people’s values.”

I think that’s a very fine - and very curious - way to live.

This is a free edition of Everything Is Amazing, a science newsletter in search of things that will hopefully make both of us go “WOW!”

Do you feel your spirits lift a little when you learn something fascinating about the world that you never knew you didn’t know? Does it make the day a little more bearable? That’s what I’m trying to do. I want you to feel that, just a bit, just for a moment - because learning about these things as an enthusiastic amateur fills me with a lot of hope about the world we live in. (What else is this cool out there? How can I learn more about it? Who else can I talk to?)

There’s also a paid version of this newsletter, where I’m trying to deliver the maximum amount of these “woah!” moments that I can dig up - and, by upgrading and joining EiA’s 700+ paid supporters, you’d be directly funding this project, helping me reach more people and keeping the lights on (which would be a relief, because this is now my full-time gig).

Want in?

Images: Timon Studler; Car And Classic Auctions; Niels de Wit/Wikimedia.

“I haven’t made my mind up and I won’t make a choice solely out of deference to other people’s values.” I totally agree with this. I don’t think it’s necessary to have an opinion or, if you even had it, voice it aloud, because you just don’t want to enter into a useless(for you) discussion/ debate, or continue with a conversation.

I have had moments were I haven’t had an opinion, haven’t chosen a side. Perhaps because I am indifferent to it, it doesn’t interest me sufficiently to decide, or maybe I don’t choose to decide at that precise moment?

Thank you for such an interesting article, Mike. See? I decided to share my opinion now. 😉

Oh my gosh! I've seen that Top Gear, I feel swindled. I feel like knowing which things I know enough about to have a worthwhile opinion and shutting up about the rest is one of the great perks of aging in my experience, but I do wish someone had told me it was OK to be uncertain and wait and see as a youth. I feel like part of the reason I made the career choices I did was because when I was 20 years old, someone said it's time to sit down, have a think, and make the decision of what you're going to do with your life.