Why Go Imperial In A World Gone Metric?

Plus: a lovely book story, happening right now.

Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and choosing enthusiasm, just to see what kind of good trouble it can get you into.

Firstly, thank you so much to those who have messaged me asking if I’m feeling better after my blood-pressure-related shenanigans. I am! Feels like things are stabilising and I’m able to focus on what I’m reading and writing again. Time to crack onwards.

Secondly - a lovely thing is unfolding as I write this. My friend Geraldine DeRuiter, author of The Everywhereist, has a new book coming out in less than 48 hours:

If you’ve been reading EiA a while, you may remember how, last year, a madly enthusiastic recommendation on Twitter turned Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone’s This Is How You Lose The Time War into a bestseller almost overnight, years after it was first published (when it deservedly won the Nebula and Hugo).

I love these kinds of stories - so it’s delightful to see something similar happening to a friend. Geraldine’s book has been getting great reviews from EATER, Publishers Weekly and the formidably picky Kirkus - but it’s an unkind review in the New York Times, accompanied by an absolutely bizarre illustration of (I’m presuming) Geraldine eating her own head, which has triggered a huge wave of support for her, a ton of positive publicity she wasn’t expecting - and many preorder sales.

And as of the time I’m writing this, If You Can’t Take The Heat is both an Amazon Bestseller and 333rd in Amazon.com’s ranking of “Books”. As in, all books on Amazon. The whole lot.

You can grab your copy here. (All the usual non-Amazon options are available behind that link.)

Okay! So I’m back writing, but it’ll be a few days before the next edition of EiA is with you - and in the meantime, here’s a piece from season 2 in 2021, which was one of the most unexpectedly fascinating topics I’ve ever researched, and was triggered by a simple question:

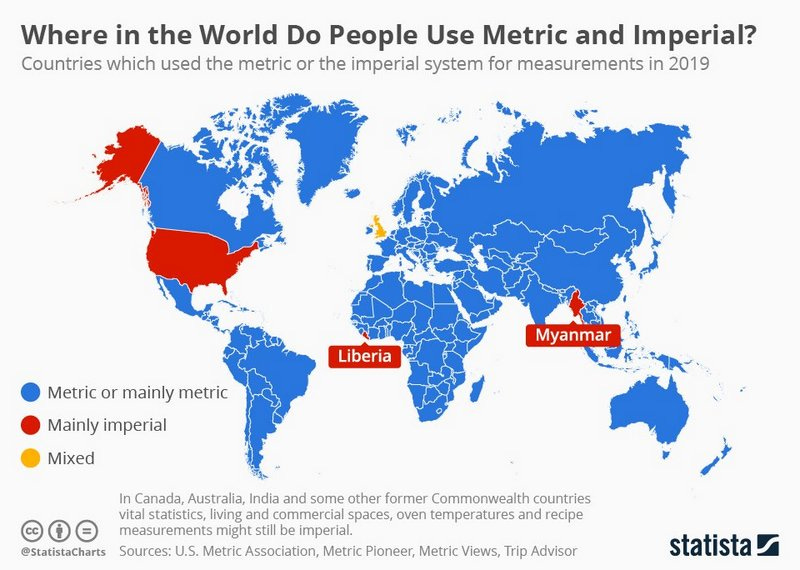

What the hell is the United States playing at here?

More questions suggest themselves:

Is Metric really that popular?

What made the U.S. and Liberia and Myanmar join forces like that?

Oh look, we UK folk are at it again with our special “trying to have all the cake and eat it” status. (This isn’t a question, just an observation.)

There’s an awful lot to unpack.

But addressing that latter point: don’t be fooled by that splash of yellow. Britain should really be a dark shade of green - ie. a little yellow, mixed with a lot of blue. We Brits may regularly use inches, ounces, miles and pounds in everyday life, but we’ve officially been Metric since 1965.

It’s interesting, and by that I mean somewhat annoying, how often non-British news makes a tangle of this. Take this story from 1999 about the unfortunate Imperial-to-Metric conversion error that led to the loss of NASA’s $125 million Mars Climate Orbiter. In that story, “Imperial” is called “English”. What they really mean is US Customary, the version of Imperial that the United States uses today, which is actually based on the units of measurement England used before we adopted Imperial in 1824. If you have to write “English” here, put the word “Old” in front of it? Ta.

So I’m from a culture that officially embraces Metric - and after a lifetime of loyalty to it, I’ve mindlessly taken its superiority for granted, never considering the value of alternatives. I mean, Metric works best! Why consider anything else?

In other words: curiosity FAIL.

When I realised this, I started my reading. And now I think I understand why 5% of the world’s population won’t completely give up on Imperial, why the United States actually isn’t being stubbornly daft in the face of perfectly sensible science - and I think I see what would be lost if everyone rigidly embraces Metric at the total expense of everything else.

Let’s take a huge step back and see how we got here.

It’s 1790, and France is an immeasurable mess in two ways.

Firstly, there’s the small matter of the entire country having just violently turned itself inside-out, in what we now call the French Revolution.

(We modern folk often assign this famous socio-political convulsion to 1789, but really, it’s best thought of as “most of the 1790s”. For example, the infamous ‘Reign of Terror’, that savage parade of executions that ignores the tedious bother of establishing anyone’s actual guilt using facts and the law? That only ends in 1794.)

And secondly, it’s just so hard to measure anything.

The problem is getting everyone to agree. France at this time has around 800 different measures being used in over 250,000 (!) different ways, many of them delightfully specific (for example, a quantity of arable land was sometimes measured in “days”, as in, how many days it’d take for a single peasant to farm it).

So far, so practical.

But then you walk a few miles to the next village, or have to answer to the regional tax-man, and suddenly you have to explain what your “30 peasant-days of land” actually means in a language they understand - and it all falls apart. A quarter of a million measurements, all needing to be converted into each other without the help of a calculator. Merde.

This was a source of great embarrassment for a new government thrown together on the rationalist principles of the Enlightenment. Something had to be done. Quickly.

In 1790, a panel of leading French scientists thrashed out a plan. This new measuring system would base itself upon the unchanging laws of Nature, using a decimal system that would make scaling calculations easy.

One of these new units? The metre, from the Greek verb μετρέω, “to measure.” The scientists decided it should be based on the size of the Earth: more specifically, one-ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator, on the meridian that ran through the middle of Paris.

At some point - perhaps after this definition was decided upon - someone pointed out that since nobody really knew how big any of these distances were (using any units of measurement), some poor, wretched souls would have to go forth into revolutionary Europe and take measurements by hand.

This awful task was assigned to two astronomers: Pierre Méchain was despatched to Barcelona, while Jean-Baptiste Delambre went to Dunkirk.

Their one-year mission: to seek out brave new heights by climbing extremely tall things, so they could take enough horizon-based measurements to extrapolate the Pole to Equator curve that would determine the length of a metre.

Well, they thought it would take a year. It actually took seven - and became a true adventure. If anything, that’s an understatement:

Along the way, Delambre and Méchain would be imprisoned, injured, almost executed, scorched, frozen, mistaken for sorcerers and spies, fired, reinstated, vilified, celebrated and then vilified again. For Méchain, the task with which he had been charged would lead eventually to his death.

Somewhere near Barcelona, at the very start of his triangulations, Méchain made a small error of computation. Once this error had entered his system, it was impossible to eradicate it. For years the knowledge of this error haunted Méchain - the thought that he alone had managed to falsify what was intended to become 'the fundamental scientific value, the measure which would for ever more serve as the foundation for all scientific and commercial exchange'. In 1804, suffering from acute depression apparently brought on by guilt, Méchain returned to the Valencian coast to try to atone for his error. There he caught malaria and died.

(From Robert Macfarlane’s Guardian review of Ken Alder’s The Measure Of All Things: The Seven Year Odyssey That Transformed The World.)

But by 1799, the new system was ready to roll out - and it was glorious. To convert between units on the same scale, you just added zeroes or moved the decimal point left or right. In comparison with everything it replaced, it was so simple to calculate it was like magic.

Except, there was one problem. A biggie.

Let’s say your government completely loses its mind and hires me (hi there!) to create a new system of length measurement, as follows:

1 Sowden (length) = 50 miniSowdens = 200 microSowdens

You’re a bit confused by all this, so you ask a govt official how big a Sowden is.

“Oh, it’s 50 miniSowdens.”

Yes, but how big is that?

“200 microSowdens!”

Uh….

“Ohh. Right, I see your point. Well, it’s taken from Nature! A Sowden is one eleventy-billionth of the distance from the geographical centre of Yorkshire to the Sun!”

Sigh.

A new system of measurement is only workable if someone has a pragmatic, hands-on frame of reference for it - and Metric, while fantastically precise in principle, turned out to be really damn hard to explain to a French tradesperson asking why the system they’d used all their life without any bother isn’t considered “practical” anymore.

The solution? Install a new ruler.

No, the other kind.

Alongside thousands of educational pamphlets, public lectures and “educational games” designed by government-sponsored private enterprises, Paris briefly became the wooden-ruler-making capital of the world.

Or at least it would have been, if it could keep up with demand. Despite heavy investment from the government, one month after the launch of Metric, just 25,000 metre rulers had been manufactured - far short of the 500,000 needed just within Paris alone.

You can guess how all this went down with the wider population of France.

By 1812, newly-installed French Emperor Napoleon decided he’d had enough. He’d sent police officers to marketplaces to enforce the Metric system. He’d spent a big chunk of the fledgling Empire’s cash reserves on education and pro-Metric initiatives. And in response, the French dug their heels in. Non, Monsieur Emperor. Vive l'Impériale!

So he gave up. His “Customary Measures” legislation of 1812, restricted to use in commerce (ie. those pesky marketplaces), rolled back Metric and introduced a series of messy compromises that tried to keep the bulk of the people happy, so Napoleon could focus his full energy on unsuccessfully invading Russia.

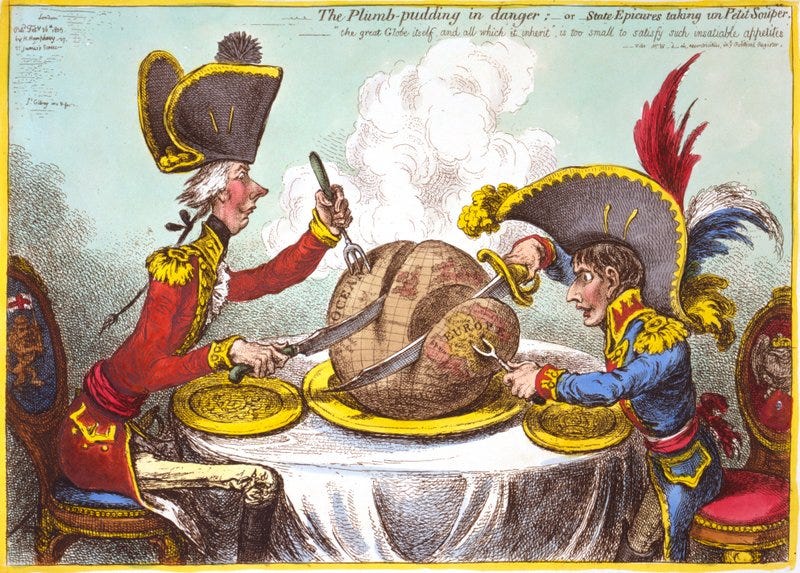

At this time, the British were taking every opportunity to ridicule Napoleon. Like how they intercepted his increasingly tortured-sounding love letters to his wife and plastered them gleefully all over the London newspapers.

And of course there were the cartoons:

Ah yes. Napoleon Bonaparte: history’s most famous Vertically Challenged Person.

There is of course nothing clever about ridiculing people’s height. This is especially true when it’s accidental and you’re emailing an editor who might publish your writing some day:

But back in 19th-Century England, heightist jokes were all the rage. How dare that tiny French nitwit strut around Europe so aggressively! We should go over and give that miniscule popinjay a damn good thrashing! Haw haw! Now bring me more brandy, you swine!

Yet again, this was an illustration of the kind of problem Metric was invented to fix. After British cartoonists learned through diplomats and spies that Napoleon was 5 feet and 2 inches tall, they saw it as a new way to poke fun at the nation’s sworn enemy - and started depicting him as a tiny, tiny man.

Unfortunately, they missed something important. The traditional French Inch, brought back into use in 1812, was actually longer than the British one. Napoleon’s real height? Somewhere between 5 ft 5 and 5 ft 7, which was more or less the average height for a Frenchman at that time…and also an Englishman, too. J’accuse, rosbif.

Sure, Napoleon may have perverted the ideals of the new Republic into a greedy, dictatorial parody of itself, ultimately leaving France shrunken and bankrupt with millions of its citizens dead in his wake - but he wasn’t unusually short. Let’s give him that at least.

Metric was reinstated in France in 1840, just in time for its Industrial Revolution - but in the words of Ken Alder, “it took a span of roughly 100 years before almost all French people started using it.”

It’s easy to leap to some narrow-minded assumptions here, like I did when I first learned the United States prefers using Imperial. (For any fellow Brits feeling a similar tendency towards smugness here: let’s not forget that the U.S. was the first country in the world to adopt a decimal-based currency, all the way back in 1792, when we Brits were still faffing around with shillings, guineas, farthings and the like.)

But people aren’t stupid. Examine the growth-cycle of a tradition that’s endured for centuries, and somewhere in there you’ll usually find a sensible, logical reason it got lodged in people’s brains in the first place. And it’s often about efficiency. Nobody wants to make life harder for themselves.

So is Metric really easier to use?

The standard way of answering this is equating “easy” with “your ability to calculate with it.” This is where Metric has everything else beat. A base 10 system, and you’ve got ten fingers to count with? Game, set, match.

But as we’ve seen, calculating is only part of using a measuring system. You need to know how big those measurements are - ideally without using something else within the same system as a reference. And while Metric measurements pride themselves on copying Nature, they do so in a way that you often can’t see in Nature. Not directly, not with your own eyes, not without help.

And horrifyingly, some of Metric was just plain made up.

Take the kilogram, originally designed to be the weight of exactly 1,000 cubic centimetres of water. An issue to consider here: the weight of “water” is not a fixed thing - its weight varies with different temperatures and substances dissolved in it, meaning there are many, many “waters”. Plenty of room for arguments that would slow the whole process down. So the scientists cheated: they made a kilo, in the form of a platinum-iridium alloy cylinder (nicknamed “Le Grand K.”) and told everyone to compare their weights against it.

Then in 1989, someone discovered this prototype now weighed a bit less than it should. Somewhere along the way, the bar had lost 50 micrograms, enough to render it useless for modern levels of scientific accuracy.

So everyone got to work again, looking for a way to tie a kilogram with essential properties of the natural world (described as “the second most difficult experiment in the whole world,” behind the search for the Higgs Boson particle).

The new definition of a kilo now relies on three fundamental constants:

the speed of light

the cesium atom’s natural microwave radiation

the Planck constant, used for measuring how atoms and other particles absorb and emit energy.

Phew. Job done?

Except…now a kilo is like the other Metric measurements: something you can’t see directly.

You can’t eyeball Planck’s constant.

You can’t see how fast light travels (hands up if when you were a kid you ever used a mirror to try to catch a glimpse of the back of your head by turning around really, really quickly).

All the nopes. It’s yet another abstract, invisible measurement for the everyday non-scientist.

Turning to Imperial - with the caveat that “Imperial” is often what people call “everything that isn’t Metric” these days.

As a Brit, I think in Miles. (Always have, maybe always will.) The Mile comes from the Latin word for thousand, and means a thousand paces. A pace is actually two steps, one with each of your feet, rather than the commonly-assumed single step - but it’s clearly a measurement invented by someone walking along at a fair old lick. A measurement wrought of human experience.

But…that’s English Miles. There are others: Scots, Welsh, Irish, German, Portuguese, Scandinavian, Italian, Chinese, Ottoman, Saxon, Roman, Arabic, nautical…and many more. The Ye Olde English type, though, is made of 5,280 feet (which becomes a deeply inelegant 1,609.344 metres.)

A Foot is - a foot. Right there in the name. Imprecisely but workably, that’s how long.

An Inch is the width of your thumb - or what you do with your fingers when someone says "what's an inch?" 😄

Go back further and you find it’s all about practical issues:

The Cubit (the ancient length measurement, not the currency of Battlestar Galactica) is the distance from your elbow to the tip of your middle finger. It’s virtually extinct now - except in the hedgelaying industry. Hang in there, guys, we’re counting on you.

The Ell is an old unit for measuring cloth, and was defined as the length of the average adult arm: the name came from the Latin for arm, ulnia.

An Oxgang or Bovate, used in pre-Industrial Scotland and England, was the amount of land that could be ploughed by one ox during a single season (usually around 15-20 acres).

Pennylands, Farthinglands, Ouncelands, Halfpennylands and Groatlands were Scottish terms for areas measured by how much taxation was due on them…

Yes, all of these lack precision, so they’re useless for modern science, and would be incredibly dangerous if used for engineering purposes. But they also tell a story of people’s relationship with the space they moved through.

A lexis of movement - perhaps in a similar fashion to the language of landscape that writer Robert MacFarlane has done so much to retrieve.

This is why I’m on the fence about Imperial now. There’s no question that Metric is necessary as a standardised, exact form used to make cars that don’t shake themselves to bits, planes that don’t fall out the sky and spacecraft that can launch themselves to interplanetary targets with mind-blowing accuracy.

But the versions of Imperial still being used by people in everyday life deserve their place in the world too.

Anyone brought up thinking and feeling temperature in Fahrenheit can tell us Celsius-reared folk something different about how we can experience the world. Anyone cooking in pounds will be thinking about food a little differently (“well, it’s just 2 cups, isn’t it?”). All these things are tiny windows into new ways of seeing what we think we already know.

And I hope the same daily experience side is true about Metric - please, Metric-lovers, weigh in with a comment! But I know of only a few examples. (When I’m packing my rucksack, I compare the weight of every item with a 1kg bag of sugar held in my other hand, so I can ‘guesstimate’ the weight of the whole thing as I go along.)

Maybe it’s too soon to ask a Brit about how Metric feels. Ask us again a hundred years from now.

In summary, dear friends across the Atlantic: I apologise. There’s nothing “backwards” about your non-Metric measurements. I’m done poking fun at them, and I hope we can get back to arguing about more pressing issues, like your outrageous habit of dropping vowels for no reason whatsoever, or why you should always say “tomato ketchup,” even though we don’t now have any other variety of ketchup. It sounds irrational, but it’s perfectly correct. Trust us on this.

I mean, you didn’t think all this meant we agreed on anything, did you?

BONUS: This brilliant explainer from Verge Science on the last big attempt to turn the US towards Metric, why it failed, and the ways scientists and manufacturers have snuck it in anyway:

FURTHER BONUS: This perfectly silly SNL sketch poking fun at America’s Imperial system. (Hat-tip to Autumn of .)

Images: William Warby, Wikimedia Commons, Luis Quintero, Nil Castellvi, Frédéric Perez.

Having been educated at school in entirely imperial, and with Australia (trust me) entirely metric, I frequently say to my husband when he names a metric measurement of something or other: 'How big is that in feet and inches?'

Also, I used to buy fabric from dedicated fabric shops, and a yard (or ell which I use when writing medieval hist.fict) ) was always the length they held out from wrist to shoulder . Made sense to me.

I know enough metric to do very basic conversions if I have to but in the kitchen, all my favourite recipes date back to imperial so I have the most fab scales and measuring jug which show both.

By the way, tomato sauce is tomato sauce here in Australia - certainly in our house and where we shop. And a meat pie will aways be with sauce, never ketchup. Same with fish and chips. Sauce all the way!

Ah, here we go. I grew up in England long enough ago to have used pounds, shillings, and pence, half-crowns, bobs, thruppenny bits, coppers, ha'pennys, and even farthings. And of course stones, pounds, and ounces. Furlongs and fortnights. Bushels and firkins. You'll find the latter in the expressions two firkin big, and two firkin small.

At school, I started with "Imperial", then metric in the form of cgs, then MKS, then SI. Chemistry at uni was metric, but work was ounces and gallons. Moving to Holland was metric, and then in the US, back to ounces and different gallons.

In Puerto Rico, distances are in Km, but speed limits are in mph, because everyone drives American cars. "San Juan 38 Km. Speed limit 50 mph"

I wrote on foolscap in England, A4 in Holland, and letter in the US (also used in Canada and the Philippines!)

Thanks for this!