Hello!

Firstly, thank you thank you thank you for signing up to Everything Is Amazing. Whatever happens with it, I’m making this project my focus for the rest of the year - but it’s really gratifying to see how many of you have signed up. Mad thanks, truly.

And if you’re reading the web version of this after curiously clicking a link somewhere, you can sign up for free here:

Right then. Let’s crack on.

Since this will be a newsletter about exploring the hidden worlds around you, I’d like to start with the most appropriate literary metaphor I know.

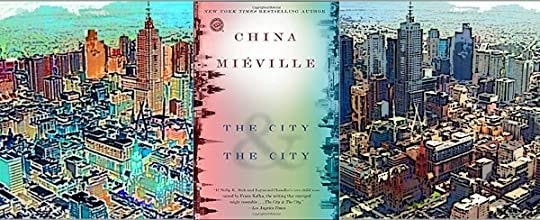

When I first heard the rough premise of China Mieville’s 2009 novel The City & the City, I tuned out. No thanks, that sounds horribly dull. I was even a bit surprised - I thought he was more inventive than that? Meh. Apparently not.

Years passed in complete disinterest. When the book was recently adapted by the BBC into a flashy four-part drama (pictured above), I didn’t make any effort to catch up with it on iPlayer. Let it pass me right by.

I thought I already knew what it was about - and the whole thing bored me senseless.

To me, one of the laziest tropes in science fiction is the “mirror universe”. At its very worst, it’s an excuse for creating cartoonishly “bad” versions of beloved characters by dimming the lights, sticking them all in figure-hugging black leather and making them tediously aggressive and shouty.

Done badly, it also feels disappointingly predictable. We know each side is there to throw the other into ironic contrast. We know that one side is the world of baddies, a whole universe of wannabe oppressors. And we know it only ends in one way: with the gateway between the universes being closed (perhaps for good), conveniently tying up all loose ends by saying “I guess it’s that other universe’s problem now, LOL.”

(Hat-tip to Fringe for being a scifi show that actually did a really terrific job of handling this scenario. I’m grateful to have gone on that journey.)

As a reader of scifi since I was knee-high, I felt all mirror-universed out. Hence, my reaction to The City & the City. What’s this? Two cities secretly in the same place, blah blah - oh please, not this again.

The unofficial City & the City artwork around the Web seemed to confirm this assumption:

Lovely. But also, yawn.

Look, I know it’s a tried and tested plotline, and I know it never fails to find an audience. But - no. Seriously. I get it! But I’m out.

In fact, I didn’t get it at all. I’d missed the whole point about what makes this story so timely, so strange and so clever. I hadn’t understood how it earns its place alongside the work of Jeff “Annihilation” VanderMeer in a literary subgenre that’s come to be known as the New Weird.

I hadn’t understood what this book was trying to show me.

“Rackhaus said something that I ignored. As I turned, I saw past the edges of the estate to the end of GunterStrász, between the dirty brick buildings. Trash moved in the wind. It might be anywhere. An elderly woman was walking slowly away from me in a shambling sway. She turned her head and looked at me. I was struck by her motion, and I met her eyes. I wondered if she wanted to tell me something. In my glance I took in her clothes, her way of walking, of holding herself, and looking.

With a hard start, I realised that she was not on GunterStrász at all, and that I should not have seen her.”

There are no alternate universes in The City & the City. There’s no magical shimmering gateway between worlds. As a piece of speculative fiction, it’s unusual because it’s so thoroughly grounded in our everyday world - the world of infuriating bureaucracy, flaky internet speeds, plastic mobile phones and soulless municipal architecture. It’s a grimy urban setting that won’t just be familiar to lovers of Blade Runner, but also to anyone who has passed through the less attractive parts of modern London, New York, Tokyo, Athens, Istanbul, any big city really.

In this sense, this is a story about the real world. Ours. Right here, right now.

There’s an old city, see. Somewhere in Eastern Europe. A city that split in two, some time in its deep past - a little like Cyprus’s more recently divided capital city Nicosia/Lefkosia, which is where I grew up as a kid. (This may explain why this story has taken such a hold of my imagination.)

These two halves of a former city, now called Besžel and Ul Qoma, have had centuries to dig their heels in, building structures deep into their societies that deny the legitimacy of the other to a literally mind-altering degree.

If you are a citizen of Besžel, you have been trained from birth to only see Besźel. It doesn’t matter that Ul Qoma is right there across the street, as brightly lit and noisy as one side of any modern main drag. It doesn’t matter that some roads and paths go through shared “crosshatch” territories where the cities overlap, putting Ul Qoman buildings in your way, sending Ul Qoman pedestrians walking all around you…

None of that matters, because you see none of it. You have been conditioned to always see Besžel - and to experience enormous mental discomfort if anything Ul Qoman catches your attention, as urgent as the pain that makes you yank your fingers away from a hot stove.

You can even be sat on the same bench in the same street as someone else (as in the image from the TV adaptation at the top of this article) - and because parts of that bench and of the surrounding street are divided up between Besžel and Ul Qoman, you’re in different cities, unable to even see, let alone talk, to one another. You might as well be in separate universes - even though you absolutely aren’t.

Here’s an even more head-scratching example:

“If someone needed to go to a house physically next door to their own but in the neighbouring city, it was in a different road in an unfriendly power. That is what foreigners rarely understand. A Besž dweller cannot walk a few paces next door into an alter house without breach.

But pass through Copula Hall [the only legal interface between cities] and she or he might leave Besžel, and at the end of the hall come back exactly (corporeally) where they had just been, a tourist, a marvelling visitor, to a street that shared the latitude-longitude of their own address, a street that they had never visited before, whose architecture they had always unseen, to the Ul Qoman house sitting next to and a whole city away from their own building, invisible there now they had come through, all the way across the Breach, back home.”

This is how the TV adaptation conveys the experience of this truly weird setup:

This psychological conditioning isn’t enough, of course. It has to be enforced.

If you are seen to be interacting with anything in the opposite city, you are in Breach - the highest crime you can commit as a citizen of Besžel or Ul Qoma. Within hours, maybe even minutes, you are picked up by a shadowy police force of the same name, bundled into the back of a van that doesn’t have Besžel or Ul Qoman plates so nobody can admit to seeing it - and then? Well, then you’re probably never heard from again.

To acknowledge the existence of the other city except as an abstract idea is punishable by your own non-existence.

In the scene I’ve quoted from above, Besžel detective Tyador Borlú is investigating a murder in a crosshatch area of his city. An Ul Qoman passerby catches his attention - and he instantly tries to “unsee” her, to filter her out of his mind. He tries. But he’s not as quick as he should be. He notices her.

There’s clearly something amiss here. Perhaps the curiosity that his job requires is making him less and less affected by his lifelong brainwashing? Perhaps his keen mind is naturally rebelling against a society set up in a very inhuman way (the setup of many a great dystopian novel)? Perhaps, without being fully aware of it, he’s taking his first steps on a dangerous journey that will put him at odds with all his conditioning, the Besžel police force and even with Breach itself?

Please read the book, because finding out is a mind-blowing joy.

(Here’s a helpful guide to the story’s weird terminology.)

This is a photo I took through an East Yorkshire bus window in 2012.

I did a little light editing to this image, but that’s more or less what I could see: a smudged, fogged, rain-spattered landscape, indistinct and mysterious. Since I spent my teens in East Yorkshire, this was not how I usually felt about the place (keywords here include “apathy”, “contempt”, “whisky” and “escape”) so it was a lovely change of perspective. I spent the rest of the journey squinting at everything going past, enjoying how alien it looked. How new.

It’s pretty common to hate the place you grew up in. Or maybe “hate” is too strong a word: say, to feel … less than charitable about its merits as an interesting place to explore and show friends around.

When you grow up somewhere rural, and your wanderlust and desire for a more exciting, cosmopolitan life makes you increasingly fed up about where you currently are, then maybe you engage in a bit of unseeing of your own. Your brain skips things, stops seeing what’s there, and interpolates what you think you already know into the gaps.

I particularly noticed this when I studied a BSc Archaeology at King’s Manor in York. During my first term, every time I entered the department I would walk through this ridiculous gorgeousness (also available for conferences in happier, less pandemical times):

But after a month or two of attendence, I walked faster. Been there, seen that. And by my third year, it was an effort to see it at all - or rather, to see it in that amazed, wide-eyed way I had as a first-time visitor.

There are very sensible reasons we tune stuff out over time. It’s been estimated that the average American (and presumably by extension the average Western European) puts around 100,000 words into their heads every day, equivalent to 34 Gigabytes of information. If you retained all of that, your head would explode.

Very sensibly, your brain keeps you mentally healthy by chucking away everything that it deems unimportant.

Unfortunately, “everything it deems unimportant” is policed by a lot of things we’re not fully aware of. Things that we don’t necessarily choose. We’re deeply affected by our cultural biases. Or the opinions of our parents and our loved ones. Or the things we read (hi there!). Or the desire to socially fit in, online and offline, which gently nudges us in the direction of the consensus we’re paying the most attention to. Or the urge to rebel, which does the opposite.

It’s estimated that a staggering 99% of the sensory world is escaping our fullest level of attention every day – and because of all those biases at work, we can’t always trust our unconscious minds to choose the good stuff for us.

What we need to do for our own good, in a way that’s safe, empathetic and socially responsible, is to learn how to Breach.

(Please don’t worry. Reading this newsletter won’t get you taken away by secret police. At least, that’s not my aim here! Becoming more curious is the polar opposite of denying hard facts and engaging in wild conspiracy theories - there’s too much of that kind of thing flying around right now as it is. This is about broadening your awareness, not narrowing it at the expense of rational thinking and basic common sense.)

This, then, is the game that’s afoot in this newsletter. It’s as prosaic as taking a few minutes out of your day to do something a little unfamiliar, a little oddball, maybe even seemingly nonsensical (until you discover its value retrospectively)…

And it’s as radical as deepening and widening the way you see the world - just a bit at first, but more and more, until at some point everything is richer and more interesting.

More about exactly how we’re going to do that tomorrow.

If you’ve enjoyed this and know someone else who might, I’d be grateful if you could let them know by clicking below! Ta.

Hello Mike from Athens, Greece! This whole twin city story brought Jerusalem to my mind. Passing the border there is still very hard due to political, religious and cultural reasons. It already is on my Goodreads to-read list.

See also Radical Wholeness

The Embodied Present and the Ordinary Grace of Being

by Philip Shepherd

Jeff Brown