Thanks But I'll Walk, Scotty

On Star Trek's horrifying transporters - and why Nature just wants to have fun.

Hello again! This is Everything is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and wonder - and, this season, what’s right above our heads.

It’s been a really tough week for science in the United States (and outside it, because of the internationally collaborative nature of research). The growing chaos unleashed by Trump’s administration has been really hard to watch, and it clearly isn’t over yet.

Since I know some of you work in the sciences or in federal government - I’m sorry, your hard work deserve better, and I hope some kind of clarity is on the way soon.

In far less globally consequential news, at least regarding humans: I’m currently mucking out my now-defunct Twitter (‘X’) account, and I stumbled across a wonderful piece of research I remember yelling very excitedly about. Here it is, newly transferred to my Bluesky account:

In fact there were actually two wheels - and between them the Dutch team recorded 200,000 visits from animals. Of those, around a thousand involving wild mice - not just investigating the hamster wheel, but clambering on and using it, in a sustained and apparently intentional way.

The same also happened with visits from rats, shrews, slugs (!) and even the odd frog and snail.

Why on earth would they do this?

“Existing explanations are that wheel running is a consummatory behaviour satisfying a motivation such as play or escape, or that it is linked to the metabolic system as a motor response to hunger or to external stimuli relating to foraging. Our results indicate that while the number of visits to the recording site decreased when no food was present, the fraction of visits including wheel running increased. This implies that wheel running can be experienced as rewarding even without an associated food reward, suggesting the importance of motivational systems unrelated to foraging.”

Their overall conclusion? It seemed to be "elective" - they just wanted to do it, even though there was no apparent benefit beyond the joy of doing it.

In other words: fun! They were just enjoying doing it for the sheer ridiculous fun of it - just like us, when we remember to resist the tyranny of usefulness.

Here’s some of the footage, including what is presumably the Usain Bolt of slugs doing his best to get that wheel spinning:

This won’t be a surprised to animal-lovers, but there’s a growing body of evidence that wild animals like to have fun as much as the rest of us - including ticklish rodents (hat-tip to Tara Haelle), rats that love driving (via this edition of ’s newsletter) and bumblebees that love rolling balls around for no apparent reason (thanks, Hugo).

I was also made aware of this beautiful and wise essay by the late anthropologist David Graeber, which argues that fun is - and should be! - at the heart of how we interact with each other:

“Our minds are just a part of nature. We can understand the happiness of fishes—or ants, or inchworms—because what drives us to think and argue about such matters is, ultimately, exactly the same thing.

Now wasn’t that fun?”

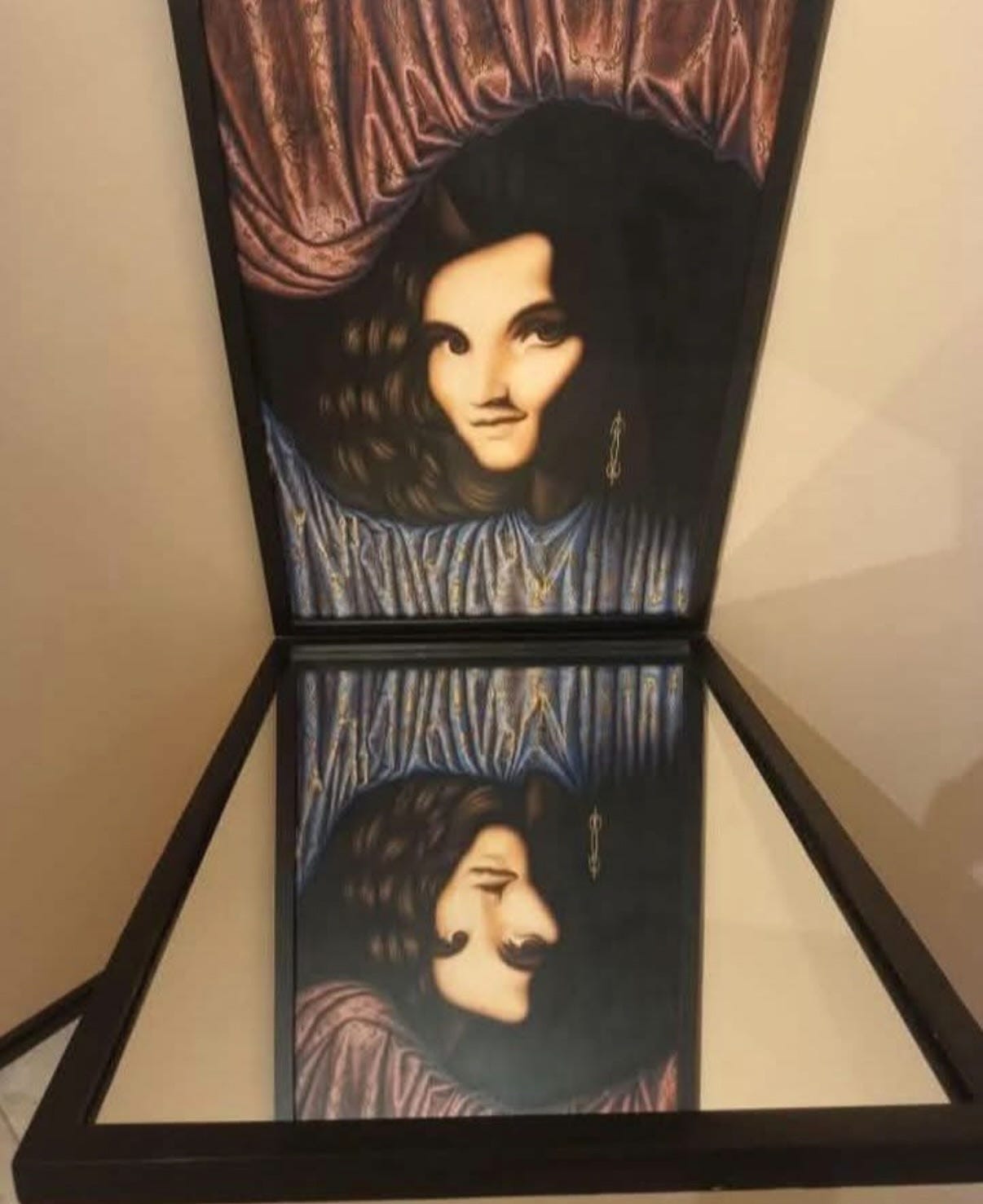

Secondly: I saw this stunner of an illusion on Threads, and it’s been haunting me ever since:

If you don’t know what you’re looking at, turn the picture upside-down and all should be revealed.

It’s another example of pareidolia, the cognitive bias that makes us see human faces in random objects (I wrote about it here) - except in this case, it’s two examples of it fighting for ascendency behind our eyes.

Your mileage may vary - you may mostly see the girl at the top or the moustachioed chap at the bottom, or it may suddenly flip from one to the other in that incredibly fun “ta-daaa!!!” way that makes such illusions a blast to play around with…

But in my case: by staring at the top image on my phone and turning the phone right round without moving my eyes from the screen, then sliding my gaze to the other image, I was able to keep seeing the girl - but the exact second my gaze flicked away and back again, it snapped into the moustache-guy. It seems like the “screen refresh” action of looking elsewhere and back again (caused by saccades, which we’ve looked at before) is enough to override my conscious awareness of what I’m looking at and replace it with pareidolia. Absolutely fascinating to see it in action like this.

(If you’re a cognitive scientist and you believe this analysis is total bunk, I’d love to hear from you!)

Okay! Today for paid subscribers, I’m leaning into my extremely nerdy side, because - have you ever thought about what’s actually going on when this happens?