Why Everywhere We Look, There We Are

The Science Of Drunk Octopus Wants To Fight.

Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, science and awe - and, coming soon in season 7, what wonders are currently over our heads.

But first, something that’s been blowing my mind this week.

I’ve had

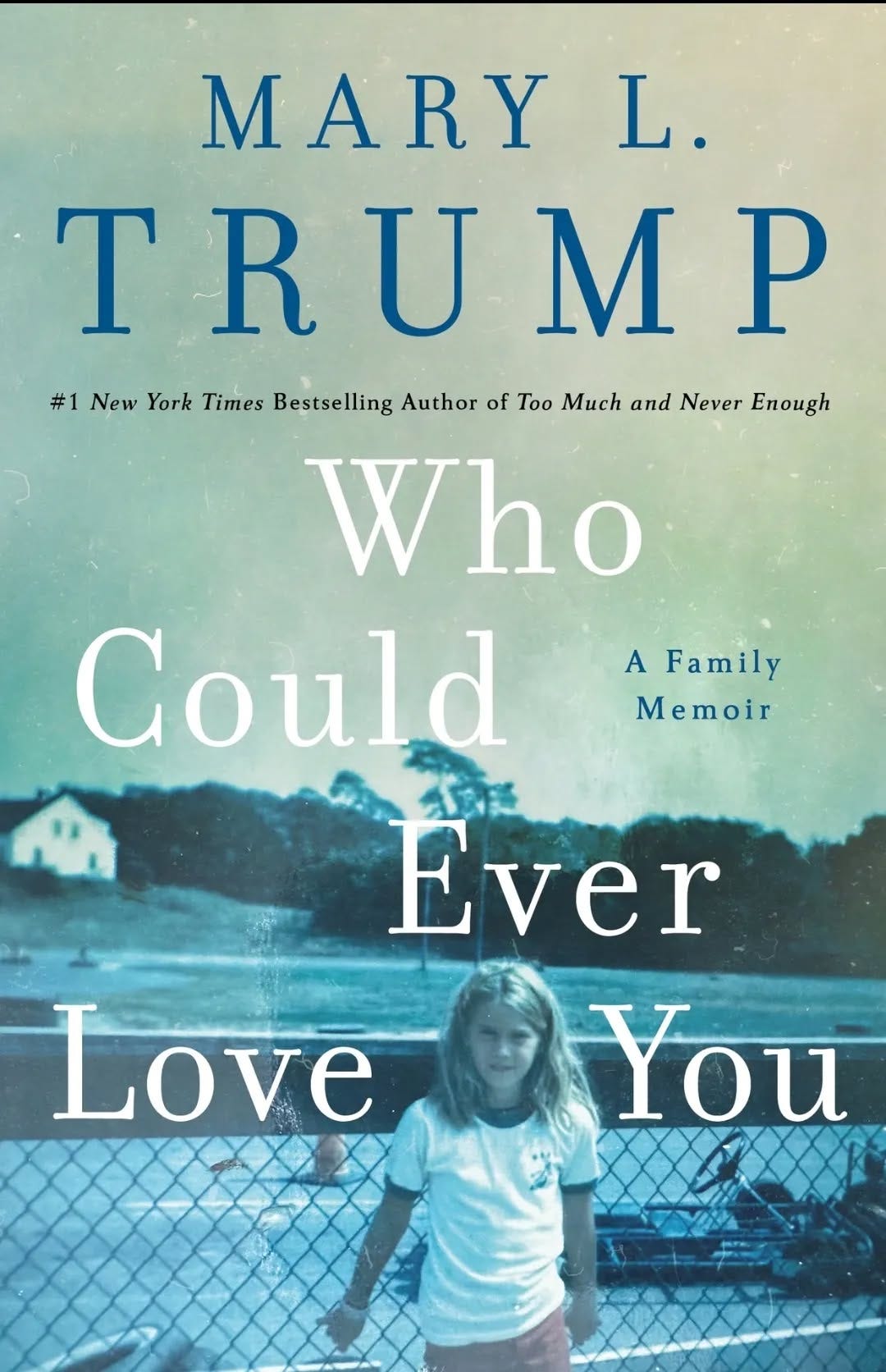

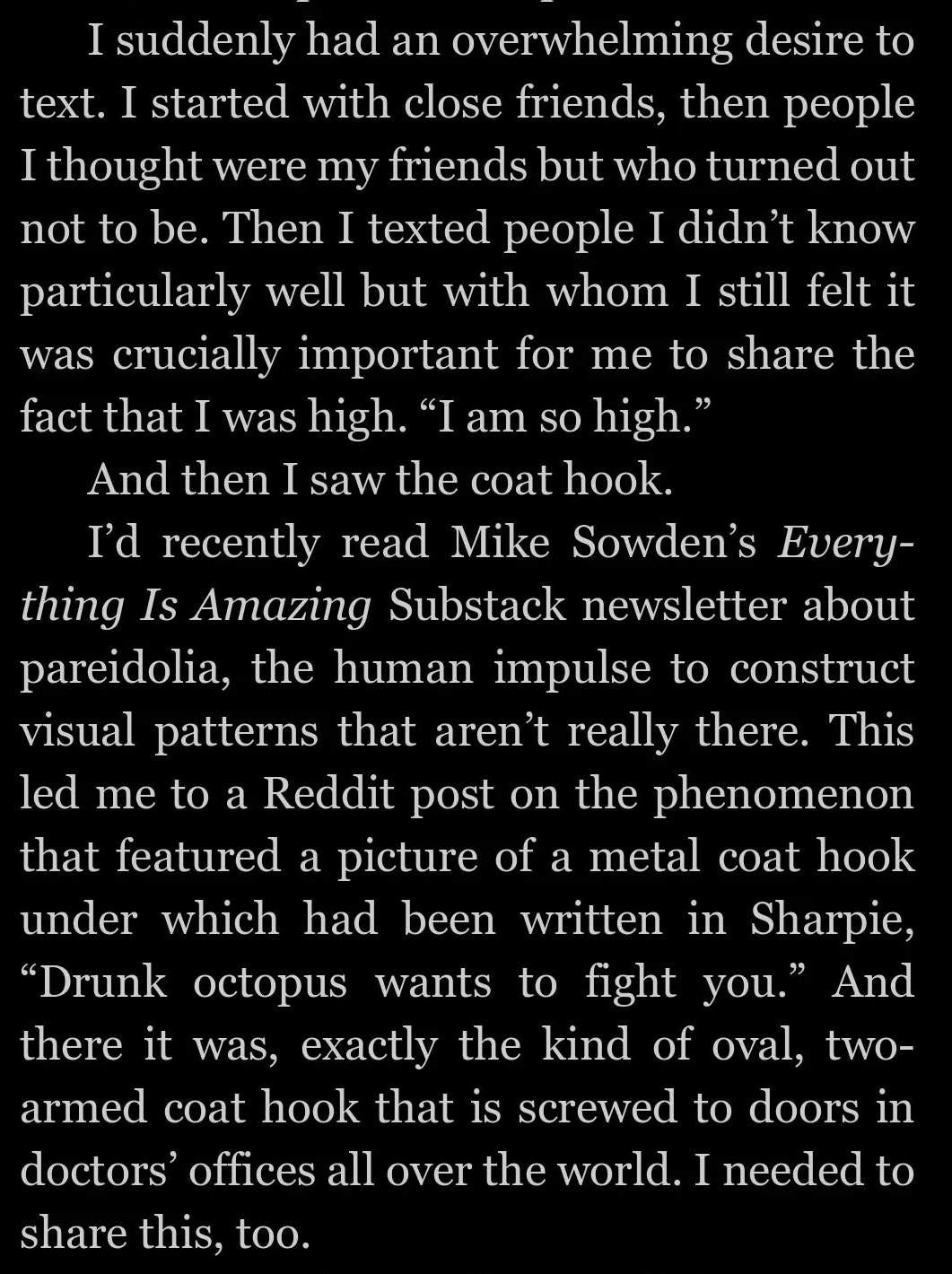

’s new memoir Who Could Ever Love You on my Kindle since it was released in the middle of October, but I hadn’t yet started reading it.Then a reader (thanks, Margaret!) suggested there was a surprise in store for me if I did that - and she wasn’t kidding. This is an excerpt from the first page of the book:

It’s not often in this line of work that you discover exactly when and how your words landed with someone, and in this case…well, I’ll just say: please go read this beautiful, raw and devastating book, and you’ll see why the context of this mention had me in a daze for the last week.

(Thank you, Mary. Whew. Blimey blimey blimey.)

In honour of all this, here’s a repeat edition of that newsletter about pareidolia, starting with this chap:

It’s a science story that’s all about humanity’s neurological obsession with its own appearance - and it starts with perhaps the most expensive grilled cheese sandwich in human history.

It’s 1994, and Diana Duyser can’t believe her eyes.

“I went to take a bite out of it, and then I saw this lady looking back at me," she’ll later tell the Chicago Tribune newspaper.

She yells to her husband to come look, and they stand transfixed above what will come to be known as the Holy Toast. What does it mean? Because it must mean something, surely?

Then she does what any of us would do: she packs it in cotton wool in a clear plastic box and waits for eBay to be invented so she can auction it off to GoldenPalace.com for $28,000.

(And if you’re wondering how it didn’t evolve into an entirely new lifeform during these ten years, here’s some science about how a grilled cheese sandwich can last a decade without going moldy.)

Clearly, What It Meant was a nice chunk of money in someone’s retirement fund, and an entire generation of Americans treating cheese-sandwich grilling with the same obsessiveness as the folk mining Bitcoin a decade later.

But no, hey: what does it mean? Isn’t it a sign of something? A message?

Say you’re the gentleman who arranged to have an ultrasound scan of his testicles, only to discover…

If these were your family jewels, wouldn’t you want to know what this face is trying to tell you about them?

Or how about that eerie countenance in the Cydonia region of Mars, first glimpsed by the Viking 1 orbiter on July 25, 1976?

I mean, doesn’t it make you think?

Yes! It absolutely does. It makes me think “isn’t it amazing how humans can look outwards and inwards at the wonders of creation, and everywhere they look, they see their own image?”

Is this kind of staggering narcissism unique to humanity, or is it a normal neurological tic that affects every other species? Do zebras look up and think “bloody hell, I can see myself in those stripey clouds! Is this a sign I’m destined for more than eating grass, running at 40 mph and surprising predators with my deceptively powerful kick?” Do snails look up at lorries and think “WOW NICE HOUSE!” and so on?

(Someone should look into this. Although I’m really not sure…how they’d do that?)

But mainly, it makes me think Oh boy, it’s so hard to see the world properly with all our cognitive biases in the way.

This particular bias is called Pareidolia, a branch of apophenia. It’s our mind’s tendency to hunt for familiar patterns in the random arrangements of everyday things (pareidolia is the visual version of it) - and it’s always looking for shortcuts. Or, putting it less judgmentally, it’s trying to save you as much time as possible.

One way it does this is using your imagination a little like Google Lens: take a “picture” with your eye, then compare that picture to the vast library of possibly-similar pictures held in your memory, and finally, render a verdict.

(Imagine if you couldn’t do this. Perhaps there would be no such thing as a glance: too slow, too meaningless. Everything would be instantly fascinating - which doesn’t sound so bad until you consider that everything would be instantly fascinating. You know that thing when you’re a bit tipsy and suddenly the back of your own hand is just amazing and you just can’t look away? Imagine that with everything, every second of every minute of every hour you’re awake every day. Yeah. No.)

So, your mind makes guesses. All the time. It doesn’t just see: it also assumes it already knows what it’s looking at, based on past experience and the surprising influence of your imagination telling you what it wants to see.

It’s why a series of Canadian banknotes issued in 1954 had to be recalled after consumers spotted the Devil in the details…

And it’s why you can look at this photo, and instead of seeing a hummingbird with its wings outstretched, you see…something else.

This bias is even more pronounced with human faces. There’s a region of your brain called the right fusiform face area that’s strongly associated with processing the patterns of human facial features, letting us spot the faces of our loved ones in a sea of strangers. And when it gets activated, it so easily drowns out other conflicting messages. It’s like a megaphone at a town hall meeting.

Only problem is: like every other process, it’s working with the same "corner-cutting” visual guesswork inputs. And it’s easily tricked into making mistakes, as with Upside-Down Adele.

And by mistakes, I mean, seeing faces everywhere. This is the You Can’t Unsee It skill, as the following image indelibly demonstrates:

We’re so easily swayed by this bias. Whether it explains, say, the Holy Toast - well, that’s another matter, and I’m leaving that well alone. (It’s very easy to use pareidolia to explain away every strange phenomenon reported in human history as perception-addled superstitious twaddle - and in doing so, use science as a blanket excuse for incurious ignorance. Let’s not do that.)

If you want to live a more curious, attentive life, this bias may seem like a royal pain in the backside. But I think it’s rather wonderful - and it might be just what we need in decades to come.

To explain this, let’s go back to the time I persuaded a team of archaeologists to celebrate the death of my boots.

It’s the final day of the University of York’s 2002 excavation of Quoygrew, on the island of Westray in Orkney.

If you have any experience of archaeological digs, the phrase “final day” might have sent a thrill of remembered horror through you. These are awful things to experience: not only do you have to wrap up weeks and weeks of work in basically no time at all (discovering a million loose ends as you do so), there’s also the not-at-all-small matter of tidying up.

With an ongoing dig, this means backfilling - laying down huge sheets of plastic and dumping all the season’s excavated soil on top, to protect the archaeology from the elements until next year. If you’re lucky, you’ll have a JCB driver at hand to haul the bulk of the soil in - but it’s still backbreaking work done at an agonising pace from morning until night, as my friend Mari is emoting quite strongly in this photo:

I’m doubly miserable, because my boots have exploded. I bought them five years ago, for my very first dig at a Roman villa in West Sussex, and they’ve accompanied me the whole time I’ve been studying Archaeology. But alas, no further: the elemental rigours of fieldwork have turned the leather brittle and each one has split almost in half. I don’t walk anymore: I flap.

I’m genuinely sad about this. I feel like I’m about to lose a friend.

So my colleagues, thinking it might cheer me up (and also because they’re desperate for some light relief on The Worst Day Ever), announce that my ruined boots will be ceremoniously interred in the backfill, to serve as part of the archaeological record for countless future generations to marvel at…

(Okay - it’ll only be until next year, when it’s all opened up again. But won’t those archaeologists, whoever they turn out to be, look at my boots and be filled with awe that we worked that hard?)

It’s a deeply solemn ceremony:

My boots are down at the end of the line, buried in soil under a makeshift capstone. James, the site’s director (looking at the camera in the above photo), murmurs something deeply Canadian, shovels & mattocks are lifted aloft, and just for a second, it seems as if the wind drops below 50 miles an hour and the rain lessens slightly, as if the Norse Gods themselves are paying tribute…

This is, of course, the kind of ridiculous nonsense that you get up to when you’re digging yourself silly on a Scottish island for 6 weeks. But it’s stuck in my memory because it feels like one of the few times I didn’t feel ashamed for getting sentimental about the things I wear.

It’s called Anthropomorphism: the attributing of human traits, even consciousness, to things that cannot technically be thought of as “alive” in the normal sense. It’s somewhat related to animism, the spiritual root of Shinto, Hinduism, Buddhism, pantheism, Paganism and many other respectful ways of regarding inanimate Nature.

Both require a leap of imagination and an unusual (in Western scientific terms) emotional attachment to the non-human world - and since kids naturally excel at those things, there’s research being done on how useful they are as conceptual tools for teachers.

So yes, yet again, it’s humans looking at things and seeing themselves. But when it comes to the things we wear, maybe that’s what we desperately need right now.

Eight days from now, the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference is kicking off in Glasgow, a few dozen miles from where I am right now - and one of the things discussed will be the new “Right To Repair” laws that have just come into force, both in the EU and in the UK. The idea is that as a consumer, you are paying for the right to be able to fix the thing you’re purchasing. It cannot be built in a way that stops you (or the repairman you hire) from tinkering with it yourself.

These laws only apply to electrical goods - but I’d love to see a wider push to encompass everything else, including clothes.

How often these days does our clothing get repaired, as opposed to just being chucked in the bin because it’s “better” to buy a new one?

This is a huge problem. We’re already throwing £140 million’s worth of clothes into landfills every year, and it’s been estimated that by 2050, the fashion industry will be using up to 25% of the world’s carbon budget, making the second most polluting industry (oil being the first).

The answer isn’t to demonize fashion. (I like wearing clothes! Almost as much as the people around me like me wearing clothes!) And there are bigger problems that also need tackling as a priority. But our wear-out-and-chuck habits are clearly unsustainable in the long run, and it’s already causing problems now.

I think we all need to relearn the skill of repairing things - or, more correctly, we need to relearn to take our clothes to the skilled folk who can do that for us.

(For example: Alpkit, manufacturer of the bivvy-tent I’ve been using to sleep outdoors this year, has an absolutely brilliant service where you can bring in your outdoor gear for repair - even if that stuff isn’t made by Alpkit.)

OK. Why would you do this? Why? Certainly not for the money: it’s rarely cheaper to get your clothes patched up. Easier? Nope, not that either. Doing your bit for the environment? Yes, but we’re still really terrible at motivating ourselves against longterm goals, however urgent they’re becoming at a global scale. For now, we need something more visceral, more gut-punchier. So - what?

I’ll tell you what, if you promise not to laugh.

We can do it because of love.

Well, okay. I’m both British and a bloke, so I have a hard time sitting with that word without squirming. Tell you what: let’s call it affection. The warmness of emotion you feel for a Thing that’s been with you a while. A shared emotional history. A feeling that’s almost impossible to put into words without other people raising their eyebrows, and without you feeling like you’re being an over-sentimental fool.

Except - no. Surely we can stop being so down on sentimental attachment. Why the hell wouldn’t we care about our beloved Things? Are we really so blinkered in our supposed stewardship of everything on this planet that we can’t imagine treating it with even a fraction of the respect we extend to “our own stuff” (which is, in every sense, Most Definitely Not Our Own Stuff)?

So maybe pareidolia and anthropomorphism have an important role to play, as we learn to undo the damage wrought on our increasingly unbalanced ecosystems.

Maybe we need to see a little of ourselves in everything, to help feel more of an attachment to the world around us and more of a sense of responsibility towards it. And maybe that’ll help us relearn to reuse - not because it’s always cheaper or easier (because it’s rarely either), but because that relationship matters to us, so we don’t want it to end just yet.

(And hey, when it does have to end - how about giving your beloved Thing a proper Viking burial? Trust me, it’ll feel great!)

Call me a sentimental old fool if you must. But I think a bit of socially accepted affection in the right non-human places might make a big difference.

UPDATE: I have since elaborated on that idea at greater length here:

Maybe It's Good We Get This Attached

During World War Two, a remarkable man called Robert Clark - later Sir Robert Clark, after he was awarded the United Kingdom’s Distinguished Service Cross - parachuted into Italy clutching a teddy-bear.

FURTHER UPDATE: Here’s a lovely example of treating your relationship with your clothing as something worth writing about, by Emily at Travelling Lines:

“Finally I decided to face my denial. I wasn’t going to get a new pair of gaiters. I was going to fix these. It really caused a shift in my attitude towards gear in general: why replace when you can fix?”

Images: Gregory Roberts/BBC Future; JPL/Wikipedia; Miami Herald; Helio C Vital/EarthSky; Youssef Naddam.

Nicely done, Mike! I've tackled both the drunken octopus phenomenon AND pareidolia in my own work, and you hit the ball out of the park with this one. The actual photo examples are gold!

You might like this one:

https://goatfury.substack.com/p/why-is-this-octopus-drunk

My focus was a bit different, but I'm pretty sure we are distantly related.

I wonder what would happen if the holy grilled cheese is consumed. Transubstantiation? Ascension? Dematerialization? Does the Vatican know about this? The kitchen should be knighted as a holy place.