Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity, wonder and surprisingly colourful ancient people.

It’s also the start of the third week of the first Big Amazing Read, and on Threadable, as a supplement to our 3-month readthrough of Alexandra Horowitz’s “On Looking”, we’re now reading a truly beautiful essay about Scotland - specifically, about the rooftops of Edinburgh - by the current National Poet Of Scotland (the Makar), Kathleen Jamie.

If you want to join in, here’s how you do it:

Go to the Threadable homepage and click on Get Started in the top-right.

Set up a new profile using your Google or Apple account or by clicking “Sign up with email”, as below.

Join my Reading Circle (see below) and click through to each text to join in the discussions.

» Click here for a direct link to my Reading Circle «

Meanwhile over here, I have something to confess, so for a change I’m using my actual face to do it.

Click below for the audio, and to contribute to my social ruination. Thanks.

Transcript:

During World War Two, a remarkable man called Robert Clark - later Sir Robert Clark, after he was awarded the United Kingdom’s Distinguished Service Cross - parachuted into Italy to join the forces working behind enemy lines, as part of Britain’s Special Forces Executive, nicknamed “Churchill’s Secret Army”.

After spending a harsh winter fighting with the partisans, he was betrayed and spent the rest of the war in Italian and German prisons, being liberated and returning to London, meeting the woman who would become his wife for the next 63 years, and then being posted to the Pacific theatre until late 1946.

Perhaps you’re forming an image of him right now: lantern jaw, stiff upper lip, twinkle in the eye above a clipped moustache, that sort of thing. Shoulders you could iron a shirt on. Every part the noble British wartime hero.

But what would you think if I told you he took his teddy bear with him? How would that fit with your ideas of British wartime masculinity?

It was with him when he parachuted into Italy.

It accompanied him in those Italian and German prisons.

It remained with him all his adult life - and would be joined by around 300 others, because Sir Robert Clark absolutely loved teddy bears.

Stuffed toys go back at least as far as the Romans in 300 BCE, and probably a lot further - but as far as I’m aware, archaeologists usually assume they belonged to kids. Why on earth would fully grown people need plushy animals, or whatever the scratchy, leathery, unpleasantly hairy equivalent was back then?

The scientific study of emotional attachment to material things seems to be pretty new, and a lot of it comes from late 20th-Century research by John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth and Donald Winnicot. According to their theory, it’s largely about the quality of our parenting - if we were brought up in an emotionally aloof way, we’d tend to make other non-human attachments to compensate. We’d also have a period of transitioning from being fully reliant on our parents to becoming aware that we’re also Ourselves, separate from them - and when that rollercoaster kicks in, we cling to our toys and blankets a little harder.

If that’s true, what does that mean for people like Sir Robert Clark? Are they broken or undeveloped in some way? Is seeing a non-human object as an extension of your personality something to worry about, something pitiable, eccentric or crazy?

Well, obviously it’s about what that object actually is. Modern men and women clearly like playing with grown-up toys (albeit when they feel nobody is watching, eg. on their phones) - and it’s especially true during tough times, when toys of all kinds can anchor us to calmer, simpler periods in our lives. But that’s what’s going on inside us, and not being confessed publicly. Outside of us, there’s still that sneer hanging in the air. Isn’t this kind of play, this recreational attaching, seen as a contemptibly childish affair?

I wrote about this a while back when I looked at pareidolia, our tendency to see human-like shapes in random patterns:

From there it’s just a short leap to anthropomorphism: the attributing of human traits, even consciousness, to things that cannot technically be thought of as “alive” in any scientifically recogniseable sense. I do this all the time and I’m generally not ashamed of it, although that really depends on who I’m with and how much I don’t want them to see me as a sentimental twit.

(One thing I like about anthropomorphizing, which isn’t spelling the word “anthropomorphizing” - it’s a nice antidote to one of humanity’s worst inventions: attributing value to objects not based on what it takes to make them, not based on what they can do, or the emotional impact they can have on people’s lives…but just on how much money they cost. It’s just about the bucks. Great job you did there, capitalism.)

Anyway, a few weeks back I lost my small rucksack. I got it from Decathlon in Barcelona in mid-2019, which means it’s accompanied me into my new life in Scotland and through the pandemic and it’s pre-dated the existence of this newsletter. In a functional sense it’s a great little rucksack, but it’s also about the years we’ve spent together. I was gutted when I realised I’d lost it - and delighted when a few weeks later I spotted it hanging on a peg in the cafe I occasionally have breakfast in, which is how I left it there in the first place.

We’ve all lost something that’s easily replaceable and felt oddly bereft, so here something more absurd, so you can look down your nose at me properly.

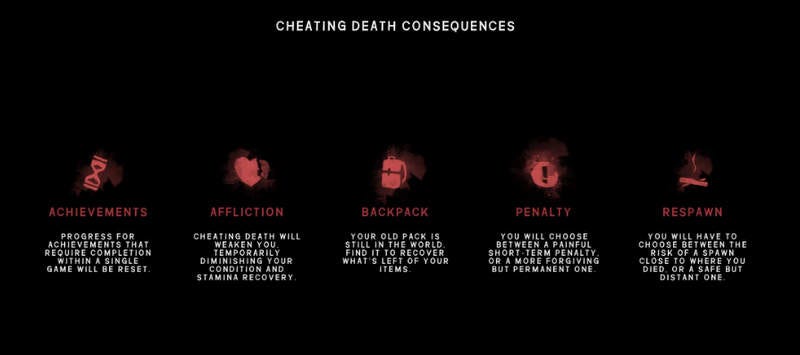

A couple of weeks ago, a videogame called The Long Dark released its latest update, which for the first time allows you to cheat death. It’s a permadeath survival game set on a fictional abandoned Canadian island, all snow and mountains and frozen bottles of maple syrup, and you only get one life. If your character snuffs it, there’s no save game to reload, you’re just done.

So you stagger from place to place, desperately trying to scavenge enough items and calories to survive - it’s uncomfortably like my time as a travel writer, so I don’t know why I find this game fun rather than triggering, but anyway.

Now along comes this new game update - and if you do something daft that ends up getting your game character killed, well, now they don’t have to die. You can cheat death, but at a hefty cost, which includes losing your gear. All the stuff you’ve spent hours of game-time finding and packing into your possessions.

This happened to me last week, and I lost all my stuff. And it was traumatic. I was actually upset, there with my late-night cup of tea held in mid-air in front of my laptop, frozen in incredulous horror. One part of my brain was shrieking Get a grip, man! It’s a game! - and the other part of me was in deep, visceral mourning for my ptarmigan-feather-stuffed sleeping bag and brand new sporting bow.

This is ridiculous. I’m a 53 year old man who writes emails for a living. I’m not even parachuting into wartorn Italy - there’s no great heroic act I’m undertaking that could turn this into an understandable if quirky coping mechanism. I didn’t have an unhappy childhood, I like to think I’m reasonably well adjusted (don’t write in, please), and I am not, as far as I can tell, a tortured artist. It’s faintly pathetic.

I can never tell anyone about this, I solemnly promised myself, little knowing I’d blurt it out in an email a week later to over 25,000 people. If you all rise up and destroy me now on social media, I guess I have nobody to blame but myself.

But here’s a funny thing about all this. In 2018, after my Ma passed away, I sold my family home - and in doing so, I had to go through all my possessions, everything my family and I had accumulated since I was born, so I could decide what I was going to keep. At least 95% of everything had to go - what wouldn’t fit into my backpack or in a few boxes at my aunt’s house would have to go in a small rented locker in York. There was nowhere else for it. A houseful of material memories that were impossible to keep.

What made this process bearable, for the months and months it took to sort through everything, was the way I’d first learned to do it while playing The Long Dark. In that game, you can only take what you can carry - and there I was in real life, in much the same situation, able to make those same decisions again and again without falling apart.

So yes, The Long Dark is just a piece of entertainment, but like any entertainment it can also act as a kind of self-archaeology of grief and loss. It teaches you the power and even beauty of just enduring, to see what's round the next corner. This is useful because bereavement can take all your hope away, so for a while at least, enduring is all you have - so in keeping the videogame version of myself alive, I’d also learned a few tricks for keeping the real version of myself in one piece.

Teddy bears, like videogames, are things. But there is real value, and no shame, in connecting with things when they remind us of better ways to show up in the real world. So I really liked the conclusion to historian David Cannadine’s piece on teddy bears for the BBC in 2013, from which I got the previous story about Sir Robert Clark.

Cannadine writes:

“Perhaps it's that bears represent the happy security of a childhood friend who never changes or lets you down. For whatever reason, teddies appeal to both children and adults of all ages, in ways that stuffed elephants or tigers or monkeys or ostriches or dolphins never quite do.”

“Children and adults of all ages.” Thank you. Because really, there’s no shame to inflict here, not with this benign, empathetically curious kind of attachment. We’re creatures that thrive by reaching out and connecting, and we have the imagination and the intellectual bandwidth to connect to ideas in stuffed-animal form as much as with other people, if only we can get over the social embarrassment of doing so.

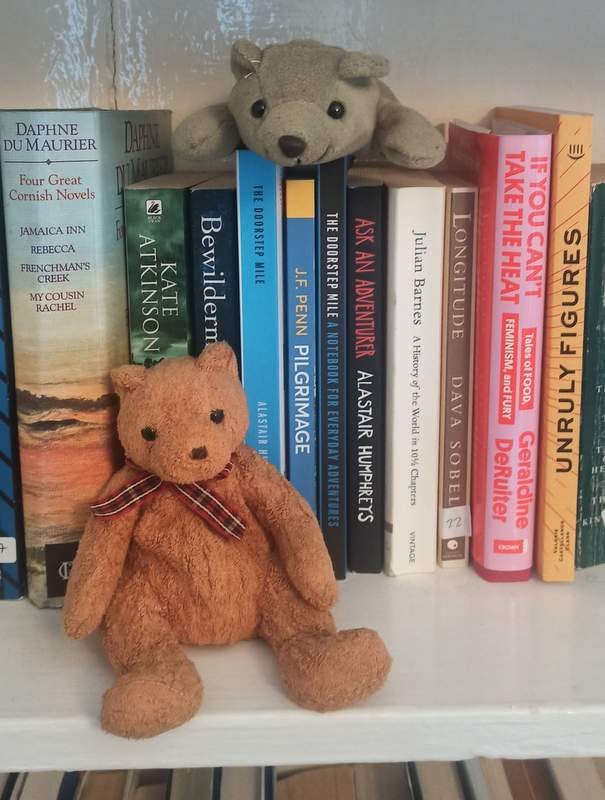

So let’s imagine someone, a man in a room in southwestern Scotland, writing a newsletter. Let’s imagine that around ten years ago, he was passing through a post office in York when he saw, squashed up against the bars at the bottom of a wire bin of gifts, a small teddy bear. Let’s imagine he called this bear Trevor, and Trevor accompanied the man on all his travels when he worked as a travel writer, joined by another stuffed animal that was a gift from someone during his days as an archaeologist: a weasel, called (wait for it) Weasel.

Let’s say that Trevor and Weasel now sit atop a bookcase in the man’s current flat, eagerly awaiting his next adventure, and that’s a reminder to the man that new adventures are waiting out there.

Is that a bad thing? Has the man lost the plot? Should you ring someone?

Let’s say the man suspects, or at least hopes, that all this is fine, healthy even, but can’t quite confess this publicly, so he hides it by writing in the third person. Judge him as you must.

But maybe he also thinks that we all have the equivalent of a teddy bear in our lives, including us men, if only we’d talk about it more openly - and if we did, maybe we’d care about stuff a bit more, and maybe that’d help repair our sense of stewardship over the world around us?

I just checked, and Trevor and Weasel firmly agree.

Images: Mike Sowden; kalzem (reddit); Pfüderi; Alexas_Fotos.

That vague sussuration is the sound of 24,999 people nodding in agreement whilst grinning sheepishly. The other one is in denial; he'll get there eventually.

Wonderful, moving and way too close to home for comfort, thanks Mike. x

My teddypig, Hamlet is 26. I went out to buy a skirt for a new job but passed a teddy shop and went inside and... well I did not buy a skirt that day. Hamlet has slept with my husband and I for many years and travels with us on overseas adventures. He once lost his head in Paris, but then, haven’t we all? When I took him to be repaired, the doll hospital in Melbourne told me I could have him back in ‘around 2 weeks’. When they saw my face they continued without pause: “unless he belongs to an adult in which case he’ll be back tomorrow, we’ll call you as soon as he’s ready.” So its not just you, Mike. Or me. When I’m in public with him, people often sidle up to me and whisper, “I have a teddy too!” I’m glad its not the seventeenth century, though, or I’d probably be burned for a witch for having cats and poppets.