Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a romp around the fascinating edges of modern science in search of a good, curious Wow.

Once again, this is a repeat edition from EiA’s formative years (2021-2022) while I’ve been taking a short break (as I write this, I’m returning from Orkney). The previous repeat edition is here, on the marvels being unearthed from the ancient flooded European landscapes of Doggerland - and since today’s edition involves the brain trickery that muddles up your ability to be curious, you may want to go read this previous piece on the way online clickbait hijacks our diversive curiosity with predictably awful-feeling results.

But today, let’s take a long, hard look at taking a long, hard look.

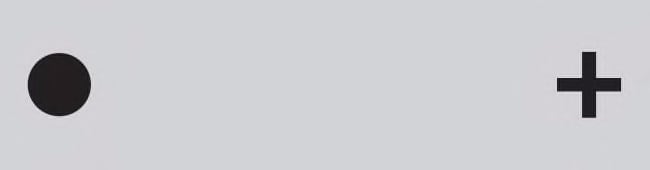

I have a practical exercise for you.

You may have done it when you were at school - that’s where I first learned it. But if not, be warned: it’s actually…sort of frightening? At the very least, disturbing.

You’re about to learn just how little you can trust your mind to tell you what’s in front of you.

Position yourself about a foot away from the screen you’re reading this on - and stare at the cross.

Now close your right eye, and move the screen a bit closer - then further away…until the dot completely disappears.

Your first reaction is probably to glance sideways. Yep, it’s still there. But when you look back at the cross, the dot disappears again from the corner of your vision. It’s not that there’s a hole there or anything. It’s just been…edited out, like it was never there in the first place.

There’s an elegant biological reason for this. You see things because light is hitting a layer of light-detecting cells called photoreceptors at the back of your eye. When they’re triggered by incoming light, they send a tiny electrical signal into your optic nerve (the ‘cable’ running from the back of your eye into your brain) - and the picture built up from all those signals is what we call “sight”.

(We recently looked at all this in much more detail for season 5’s theme of how we see colours.)

But there’s a mechanical problem here. There’s a place where the back of your eye connects with the optic nerve, like the plughole in a kitchen sink. It’s not a flat, forward-facing surface like its surroundings, and it doesn’t have the same photoreceptors.

If your brain suddenly allowed you to see this area properly, it’d be alarming, to say the least: a null signal, like a fuzzy black hole, always hovering at the edge of your vision. But you don’t see that. There’s just this edited patch - which, like the ‘Healing Tool’ in photo editing software, always paints itself the same colour as its surroundings.

(Try the experiment again with the following image. See how the blind spot is filled in black this time?)

Over millions of years, your brain has learned to lie to you. It can’t see what’s in that gap - so it just kinda fudges it, telling you there’s nothing here you need to pay attention to. Don’t worry about it. Trust me, you don’t want to see this.

It’s right, of course. And anyone suffering from a central scotoma will agree. But it’s also a flaw in your vision that you can spend your entire life not knowing about (until someone shows you an image like the one above, because they want to see how much you’ll freak out).

For usually sensible reasons, your brain hides things like this from you all the time.

Unfortunately, its reasoning for doing so is deeply imperfect.

Your mind is riddled with short-cuts and fudges that either made sense at an earlier time in human history but have since been made redundant - or they’re flat-out errors that have never made sense.

The result is that, like the citizens of Besžel and Ul Qoma, we each see the same world a bit differently. We have our perceptual quirks, and they all add up to make our experience unique.

This is one of those phrases we like to trot out to excuse other people’s idiotic behaviour: oh well, I guess we’re all a bit different, eh? Or we say stuff like “hey buddy, feel free to speak your truth” without actually considering that person’s view to be as true as what we believe. The words are easy. The thinking is really. damn. hard.

Take something as simple as colour. Blue is blue, right?

Yes - except for when it’s also white.

Why did The Dress go viral in 2015? Because we can’t handle the truth that half of the world sees a different colour to the one we see. It’s so, so difficult to take in.

(I have always seen a blue dress there. When someone first told me they saw white, I stared at them, looking for a telltale sign that they were pulling my leg. Then I saw on their face that they were searching my expression for exactly the same thing. I bet you experienced something similar.)

This illustrates why shouting at people over social media is often a deeply fruitless exercise (“IT’S A DUCK, KAREN!”) - but this is also about knowing our own perceptual differences. We like to think of our own viewpoint as…if not flawless, then at least uncommonly accurate, right? What we see is pretty much what’s actually there?

Nope. Not a bit of it.

And that’s wonderful! As thousands of EnChroma colour-blindness-correcting reaction videos on YouTube illustrate, being able to see the world differently is an emotionally overwhelming thing:

(Reckon my dad would have loved a pair of these. Alas, bad timing…)

All this gets treated as a mechanical problem, but it’s really about how the mind works. For example, if you wear a pair of glasses that flip your vision upside-down, your brain will immediately start reinterpreting signals from your eyes in an attempt to turn things the right way up again - and after about 10 days of it, your sight will be corrected enough for you to ride a bike.

That’s only half of it, though. When you take those specs off again, your eyes will naturally see everything upside-down - and you’ll have to wait another couple of weeks for that effect to go away.

(This sounds like a truly horrible way to spend a month, which is presumably why nobody else has done it in the last 70 years. Very wise.)

These kinds of neurological “edits” are relatively easy to spot. I mean, we can see them. But there’s a whole other realm of cognitive trickery that escapes our attention at the same time it shapes it.

Welcome to the deeply unsettling world of cognitive bias.

Note on the above image: while I’ve often written “brain” when meaning “mind,” there’s plenty of highly convincing evidence suggesting we also think with the rest of our bodies, with our surroundings and with our social networks, as I mentioned here. Annie Murphy Paul’s recent work on this is spectacularly interesting - and she’s on Substack now too. Go sign up.)

A cognitive bias is a shortcut invented by your mind, designed to make your life easier, by keeping you sane, safe and upright.

Unfortunately, it’s also an error. Your brain is messing up - sometimes with disastrous long-term consequences.

Now, I’ve noticed that us blokes have a tendency to use military metaphors here - a bias becoming an “enemy” you can “go to war with,” like the evil force of Resistance that tries to tear down your Art every day. If that’s a motivating way for you to think about it, full steam ahead, all guns blazing! (No, we don’t have steam-powered warships these days; yes, I probably need new metaphors.)

But really, this is You we’re talking about here. This isn’t Us vs. Them (which is itself a bias - see below). This is about metacognition, the skill of thinking about thinking itself, and about learning your own behaviour so well that you develop that rarest and most impactful of human skills: the ability to get out of your own way.

Here’s a whistlestop* tour of four cognitive biases that royally get in the way of living a curious life. I’ll be spending a lot more time writing about them in future newsletters (& even more time testing out ridiculous things that might serve as useful workarounds) - but for now, here’s a quick summary of each.

*Another age-of-steam saying. I really must get out the house more.

1. “Everything Is Awful”

This is Negativity Bias, also called positive-negative asymmetry. It’s the human tendency to pay special attention to potentially threatening things, which is why we can’t stop reading the most distressing news headlines every day - and exactly why the news keeps serving them to us, as I wrote here:

Not only are we exhausted from all the depressing news out there, we’re also hooked on it. It seems we can’t stop obsessing over what’s crappy and awful, even if it’s wildly unrepresentative of the amount of crappy, awful things out there.

Negativity Bias is stitched deep into our minds. Unpick it, and we’ll probably come apart. And hey, a little bit of negativity keeps you from wallowing in the kind of smug, thoughtless Oh-it’ll-be-fine-stop-moaning optimism that makes some people’s shins so incredibly kickable. (Read Brendan Leonard’s post here on how to manage negativity in a healthy way.)

But this bias can also be really, really toxic. It can masquerade as reality so convincingly that it can plunge you into despair about the state of the world and how much everything and everyone sucks, leaving you hyperanxious and traumatised, killing your questions and suffocating your curiosity.

Let’s be clear: in the Cognitive Bias Cinematic Universe, this one is Thanos. (Or Kang, if you’re reading this a few years in the future.) It’s powerful, it’s cunning, and it’ll never stop trying to bring you down.

Avengers Assemble.

2. “Everything Is Boring”

You’ve probably already heard of Confirmation Bias. It’s what keeps us in our social bubbles, sharing the same stuff, hanging out with like-minded people, paying the most attention to things that confirm our existing beliefs, and growing more & more convinced that our relatively narrow experience of the world is the only important one.

(It works in the opposite direction to curiosity, which tries to push you towards what you don’t yet know.)

Confirmation Bias is your mind trying to keep you comfortable. In the words of author Nir Eyal, “you seek evidence that confirms your beliefs because being wrong feels crummy.” Admitting you’re wrong is embarrassing and humiliating, so why wouldn’t our brains do everything in their power to save us from experiencing that suckiness?

Unfortunately, always being right means you never accept you’re wrong. It also means you’re never exploring the “I guess another way to answer this is…” questions that lead to revelation, wonder and jaw-dropping awe. Because, why bother? You’ve got the right answer already!

Here’s Pulitzer-winning journalist and self-described “wrongologist” Kathryn Schultz on why it’s so, so important to get things wrong.

In Kathryn’s words:

“This attachment to our own rightness keeps us from preventing mistakes when we absolutely need to and causes us to treat each other terribly. But to me, what's most baffling and most tragic about this is that it misses the whole point of being human. It's like we want to imagine that our minds are just these perfectly translucent windows and we just gaze out of them and describe the world as it unfolds. And we want everybody else to gaze out of the same window and see the exact same thing. That is not true, and if it were, life would be incredibly boring.”

That’s Confirmation Bias for you. It tries to make everything incredibly boring. It’ll never teach you anything new - and you’ll get more and more bewildered at how the world makes less and less sense. Uncomfortable spoiler: it won’t be the world, it’ll be you.

Let’s not, then. (We’ll look at how another time.)

3. “Everything Is Short-term”

You know when you’re aware that spending ten minutes a day doing something can eventually add up to a powerfully positive effect on your life - but because there’s always more pressing things to deal with, you never get around to doing it?

At a certain point of the year, the cumulative weight of this will land on you like a ton of bricks. You could have been working on it every day! It’s only ten minutes! But you spent days, weeks and months putting it off. Your horrified conclusion: you’re a lazy, unmotivated person who will never amount of anything consequential. Curiosity Epic FAIL.

Don’t attack yourself like this, please. This is actually a cognitive bias. Everyone has it. It’s absolutely normal. And sure, knowing that doesn’t make you feel better about yourself, but it’s the right place to start thinking about a long-term fix for it and start genuinely making progress on these things.

Welcome to the magnificently-named Hyperbolic Discounting (also called Present Bias) which is a fancy way of saying “humans are really, really bad at motivating themselves using long-term goals.”

Or, putting it another way, your Instant Gratification Monkey is completely out of control:

We’ll look harder at this another time, because one solution is all about using empathic curiosity, which is the key skill powering kindness.

But for now, maybe test out Tim Urban’s super-stressful, super-effective advice here and here:

“Create a Panic Monster if there’s not already one in place—if you’re trying to finish an album, schedule a performance for a few months from now, book a space, and send out an invitation to a group of people.”

4. “Everything Is Either This Or That”

This one is really interesting because it might be cultural. When we think about stuff, we Western folk tend to split things into two camps and favour one side over the other. In other parts of the world, people seem less prone to this. It’s truly fascinating.

It’s called a False Dilemma (where, precisely defined, a dilemma is “a difficult choice between two alternatives”). It’s also more a logical fallacy than a cognitive bias, but I’m going to risk being yelled at by philosophers because this really needs to be part of any conversation about curiosity, so I’m including it here.

The big problem with a False Dilemma is that it dumbs a complex question down into just two “answers” - and in doing so, it lobs the grenade-like word “or” into the conversation, suggesting that you have to pick one side or the other (and drowning out anyone saying Hey, why not neither or even both?).

This is the adversarial model of knowledge-acquisition-by-blazing-argument that goes back to the Ancient Greeks and maybe a lot further.

It’s how people pick “sides,” including the stories we make out of wildlife photos: which of those puffins are you rooting for?

And it’s how we completely stop listening to each other. It’s a brick wall in the path of our thinking, it’s the end of all our questions, and it’s where we start complaining that those people over there are the problem.

Our bias towards False Dilemmas leads to a psychological effect called Splitting - which is associated with extremism, personality disorders, depressive thinking and all sorts of terribleness. The sooner we learn to move away from it (or at least work around it), the better for us as individuals, as societies, and as a species facing unprecedented global challenges in the decades to come.

No messing. We’re going to have to throw a lot of ideas at this one. More on that soon.

Speaking of brainful things - in the next season of this newsletter starting in September, I’m running a series just for paid subscribers on the power of applied memory - as I explained here a little while back.

That’s starting very soon. And until it kicks off, all paid subscriptions to Everything Is Amazing are 10% off.

With one of them equipped, you’ll be able to read everything behind the paywall, get my upcoming non-fiction storytelling course for free, and grab a personal ‘curiosity call’ to motivate you to chase your own nerdiness in a similar way, as I explained here.

(You’ll also become the reason I can keep writing this thing, which is now my fulltime job. Without subscriptions it can’t exist, and I‘d be forced to find an actual new line of work. So if you’ve enjoyed anything in this newsletter so far, this is exactly how you could help me create a lot more of it.)

Click below to sign up with a 10% discount:

Thank you so much!

Images: Fakurian Design, Jeremy Zero, Petri Heiskanen, Wait But Why.