Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and wonder.

I hope you are well, I hope your extremities are warm, and I suggest you immediately pop the kettle on - you’re going to need a hot drink inside you for the cold and increasingly grim second half of this newsletter…

But before that, a few cheerier things.

Every year at this time, Brendan at Semi-Rad.com republishes a particular essay he wrote in 2012. It’s about the power of enthusiasm - the infectiously fun kind, the kind kind, that hard-to-pin-down, easy-to-identify emotion that’s the source of so much mad joy in this world, and the endlessly renewable stamina we need to do all the absurd things we know, deep down, that we’re here to do.

Without getting Brendan’s permission in any way (apologies & maybe see you in court, Brendan!) I’m going to repost part of the intro here:

“I have put a lot of thought into it, as it must be the most widely-read piece of work I’ve ever put out there, and it was now more than a decade ago. Sometimes I feel like Mariah Carey probably feels about her No. 1 bestselling song of all time, “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” which everyone in the U.S. has probably heard at least a hundred times since it first came out in 1994, and it continues to pop back up every holiday season, like a musical Pumpkin Spice Latte, or the McRib, or the UConn women’s basketball team.

You might think the person who wrote this piece is constantly whooping and high-fiving people when they’re out in the world. Sometimes I wonder if I should be doing those things, especially when I read this piece again. I am actually much more chill in person, despite my medically inappropriate consumption of coffee. But I do espouse the idea of Practicing Maximum Enthusiasm. I am generally trying to look for the bright side. and happy for you when things you want to happen happen, even if I’m personally not that excited about new skate skis or adopting cats or whatever. I’m just happy you’re happy.

I’ve written a lot of words over the years, and sometimes I go back and read them and realize I don’t 100% believe something I wrote in 2015 anymore. But I’m still pretty OK with everything in this piece.”

Every year, many thousands of Brendan’s readers are pretty OK with it too - so I hope you’ll join them by clicking here, reading it, and then enthusiastically living it for the rest of 2024.

Also, a quick shout-out to my friend

who is tirelessly enthusiastic about finding great things to read on the internet, and just published her latest roundup:(Every month I’ve been helping Jodi format the links, since she’s mostly assembling these newsletters on her phone while laid flat due to an ongoing cerebrospinal fluid leak - she explained things to CNN here - but as yet, Substack’s mobile app doesn’t have a newsletter writing/editing option that allows for easy link editing, so it’s all a bit tricky for someone with limited standing-up time. Would love this functionality, Substack!)

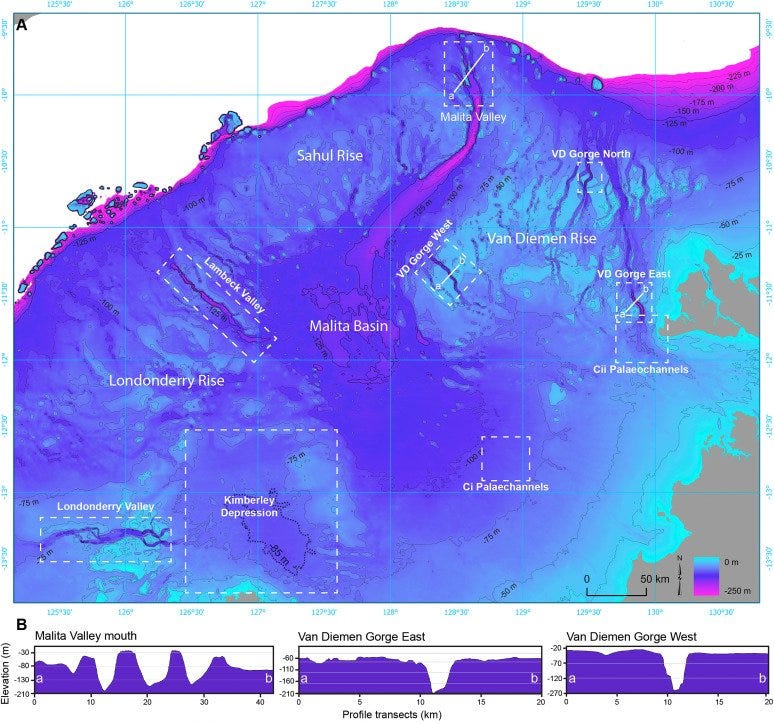

Secondly, if you’re as fascinated as I am by Northern Europe’s ‘lost world’ and the recent mapping of Zealandia - now it’s Australia’s turn!

In a study just published in Quaternary Science Reviews, a team headed by archaeologist Kasih Norman from Griffith University (Brisbane) has reconstructed the ancient topography of the continental shelf surrounding Australia - and found that between 27,000 and 17,000 years ago, when the sea was low enough to connect Australia to modern New Guinea, there was a vast shelf of land extending off the continent’s current north-western edge (now under the Indian Ocean), and it contained both an inland sea and a huge freshwater lake:

Perfect for habitation? The modelling suggests so - and the team believes this 400,000-square-kilometre landmass could have been home for anything up to half a million people until the sea reclaimed it around 14,000 years ago. (In comparison, the maximum population of Doggerland has been estimated to be not much more than 10,000.)

In Norman’s words, quoted in New Scientist:

“This massive landscape that is not there now would have been unlike anything that we have in Australia today… To have a freshwater lake of that size next to an inland sea is just incredible and people would have been living across it. This is a lost landscape that people were using.”

And thirdly, I was recently reminded of this glorious telekinetic hoax in a coffee-shop in New York, set up to promote the remake of Carrie (2013) - and every time I watch it, I love it just a little more.

What a great job they did with this prank - and how close we assuredly all are, all of us, to believing that such a thing can exist under conditions as convincing as this:

Okay!

In tribute to the below-zero temperatures currently setting the UK crunchy and aglitter right now, I’m bringing back one of the most horrible things I’ve ever written.

It’s hopefully not horrible as in “unreadably bad” (I wouldn’t inflict any of the worst of my past writing on anyone except myself after a stuff drink or two) - but horrible as in “instilling a sense of immense Yikes upon the reader”.

While doing a piece of travel writing for a magazine about some idiot getting lost on the North York Moors (yes, that idiot was me), I got interested in the limits of the human body in cold conditions. I knew of friends who had endured temperatures of up to -30 Celsius in some of the bleakest places in the world - and of people who had died of hypothermia in more or less their own back yards. My ghoulish curiosity kicked in. What actually happens when you freeze to death? What was the science of this awful, awful thing?

So I did my reading, and wrote it up on my personal blog - and thanks to a now-defunct website called Stumbleupon, it proceeded to go mildly viral and freak out upwards of a hundred thousand people.

Here’s the updated 2024 version. I hope it makes you appreciate the next warm thing you wrap your arms around.

When we say “cold”, we usually mean one of two things. The first is the oddly delicious foot-stamping, hand-rubbing, nose-blowing kind that millions of us Brits experience less and less frequently these days, as we trudge through the slush, or curse when the snow billows in our opened car doors.

And then there’s the other kind.

You can be sure you’re at your optimum core temperature because you’re presumably lucid and conscious as you’re reading this. In fact, your ongoing survival is dependent on it, on hovering somewhere near 37°C every single day for the rest of your life. It’s a fine line. Stray above or below it by more than a little, and you will start to die.

Luckily, you’re amazing. You’ve already been fitted with an incredible piece of biotechnology, a kind of super-advanced thermostat called a hypothalamus. This almond-sized marvel, buried deep inside your brain, is why you’re alive today.

Take a moment to say thanks. (I’ve just thanked mine).

Your hypothalamus performs a range of invaluable and breathtakingly elegant roles, but the one we’re giving thanks for is the maintenance of your good self as a homeotherm – an animal with a steady core temperature usually above that of its surrounding environment.

Thanks to your thermoregulatory system (heroically led by the hypothalamus), you never need to worry too much about keeping just the right temperature – your body’s got it covered.

Usually.

It takes a lot to overwhelm your hypothalamus’s capacity to keep your core temperature stable. But it can be done. And once it happens, the effects are rapidly disastrous.

So let’s chill out a little and see what happens.

37°C (with below-freezing air temperature exposure)

There’s a dark little truth about your hypothalamus – it doesn’t care if you’re feeling cold on the surface (which is why so many people with frostbite have lived to tell the tale). All that matters is what’s going on inside.

When the wind-chill starts savaging your exposed flesh, your capillaries squeeze the blood out of your skin, driving it inward where it can assist in maintaining your core temperature. Your paling, cracked, pinched extremities are being offered up for sacrifice – and unless you’re one of the lucky few who has a natural hunting response or, through a genetic quirk, an unusually thick and widely-dispersed layer of brown fat, it’s going to start to hurt.

What’s the common response to a surface chill? Vigorous exercise of the flexing, stamping, wiggling kind, and a tendency to increase your pace of movement. This works a treat in the short term, burning up inner stores of energy and elevating your overall body temperature until you’re comfortable again.

The contrast is delicious, so you keep moving, keep burning up – until you start to sweat. Sweat cools (that’s its job) and before you know it, you’re clammy with freezing perspiration that drags your temperature lower and lower.

Worse still, your skin is too cool to efficiently evaporate the sweat away, so it clings on, sucking the heat from your bones. (This is why moisture-wicking garments are quite literally lifesavers.)

36°C

One degree down, and boy are you aware of it.

Your muscles are tightening up (more formally, you’re experiencing pre-shivering muscle tone). It’s a forerunner of the muscle contractions that are shortly going to make you a clumsy invalid.

Now’s the time to adjust tricky straps and tie shoelaces – another core temperature drop and you’ll be a juddering, uncoordinated mess.

35°C

You’re a juddering, uncoordinated mess.

As mild hypothermia sweeps through your body, your muscles leap to your defence with frenzied high-speed involuntary contractions, better known as shivering.

Exercise generates heat – but with an unfortunate flip side. To spasm so violently, those muscles require an increased supply of blood – and so shivering can accelerate the rate of cooling at your core.

Plus, it’s horribly unpleasant. All your muscles have already tightened up, and now they’re shaking as well. This applies to all your muscles, even those around your eyes. Your basic senses are starting to go…

33°C

…but strangely, you don’t care. Your body is responding logically and sensibly by hoarding its resources and making itself slower and smaller in every way it can (this may save your life later on) – and the effect right now is to dull your thoughts, drugging you into apathy and then a stupor.

Whatever. Yawn. A little sleep before you get back to fighting the cold is just what you need, surely?

31°C

Shivering hasn’t worked, so your body abandons it. (This helps you doze off).

Your blood is starting to thicken, slowing its progress through your body. Your oxygen consumption has dropped significantly and your oxygen-starved brain is struggle to string a thought together – other than “I really need to pee“, thanks to all the inwardly-pushed body fluids flooding your kidneys.

30.5°C

If a loved one rescued you right now, you wouldn’t be able to recognise them.

30°C

Your heartrate is becoming arrhythmic, further restricting the amount of oxygen reaching the brain.

Time for Harvey to make an appearance. In your stupefied, thermal free-falling state, you’re hallucinating wildly. You probably think you’re being rescued.

But then …

29.5°C

…you’re suddenly on fire.

It’s a bleak irony that as you freeze to death, there comes a point where your skin feels like it’s alight, prompting you to struggle out of your clothes. This is called paradoxical undressing, and may happen because your ailing hypothalamus pops a fuse – or because it tries a last-ditch attempt at warming you, flinging all your capillaries open and giving you the mother of all full-bodied blushes.

You’ll also feel the urge to crawl into a small space (terminal burrowing), a mechanism that often makes it harder for rescue parties to find severe hypothermia victims.

This is not the finest hour of your survival instincts.

28°C and below

You’re down – but not necessarily out.

Your skin may be blue and cold, your pulse indetectable and your heart may be beating too slow to keep you alive under normal circumstances…but these are not normal circumstances. Remember that your entire body has slowed down as you cooled, including the most critical part of it, your brain. Your oxygen supply is way down – but so is the demand for it.

You’re not dead: you’re suspended between life and death.

Or put another way, as mountaineers like to say: “you’re not dead until you’re warm and dead.”

Now the key to your survival is rescuers who know how to revive you. If they warm you too quickly, this delicate balance between supply and demand will be broken and you’re history.

“In “rewarming shock,” the constricted capillaries reopen almost all at once, causing a sudden drop in blood pressure. The slightest movement can send a victim’s heart muscle into wild spasms of ventricular fibrillation. In 1980, 16 shipwrecked Danish fishermen were hauled to safety after an hour and a half in the frigid North Sea. They then walked across the deck of the rescue ship, stepped below for a hot drink, and dropped dead, all 16 of them.”

– “Frozen Alive,” Peter Stark, Outside Magazine (1997).

If you don’t fancy trusting your life to the specialist medical knowledge of the first bunch of people (probably strangers) to stumble across you…well, I don’t blame you. Ask yourself: what would your first instinct be if you found someone almost frozen to death? Warm them up as quickly as possible? Me too.

So, make sure it’ll never happen. Keep yourself well-wrapped, plan your freezing-weather journeys in advance, let your loved ones know where you are & where you’ll be - and then put your trust in the thermostat inside your head. After all, it hasn’t done a bad job this far.

Images: Mary Lane; Brendan Leonard; Kasih Norman; Rodion Kutsaiev; Phil Muller, Osman Rana.

I will read when I have time for full attention but in the meantime am here to inform you that it’s currently a blustery -40 here, which I don’t even have to translate from Fahrenheit to Centigrade because they’re the same! Meant to get colder into evening, overnight, and tomorrow. 🥶🥶🥶

A pleasant read, not least because I'm under a pile of blankets with the wood stove roaring!