Hello! This is Mike from Everything Is Amazing.

If you’re a new reader and you’re wondering why I’m suddenly talking about reading books and not the science of memory or clouds or islands or the like - it’s because of this…

…which I’ve been reworking a bit, so if you’re not a new reader, you’ll find a few updates below (and thanks for your patience while I iron out these wrinkles in the process).

In this first Big Amazing Read, we’re galloping through Alexandra Horowitz’s On Looking - which essayist Maria Popova described as “breathlessly wonderful” and I’d say that’s absolutely correct.

Anyone can take part in this read-through of On Looking! All you need is to get hold of a copy of the book and read it in your own time.

New paper copies are a little hard to find (there’s only been one version published, as far as I can tell). If you’re in the UK, the Simon & Schuster page for the book has a lot of great links; if in the US, try the Barnes & Noble page.

It’s on Amazon here (cheapest as a Kindle e-book) - and it’s also on Audible here, read by Horowitz herself.

If you want a taster of the whole book, the introductory chapter - accompanied by my own commentary in the margins - is available to read on the social reading platform Threadable.

You can access that introductory chapter by clicking here.

When I first published that excerpt, dozens of you went over to leave comments on it! So now there’s a fascinating mass of rabbit-holes of ideas to check out in the margins over there. This is exactly why I love reading a book with others: I quickly discover that other people’s takes on it are far more interesting than mine, and hooray for that kind of revelation.

However (and this is where I’ve needed to rework this part of the Big Amazing Read)…

Threadable is awesome as a book discovery engine: you click through to read a bit of the book, prompted by some excitable enthusiast like me, and then hopefully you’re sufficiently hooked to want to read the whole thing, so you go buy it. You win, the author wins, Threadable wins, and I’m a happy book nerd.

Here’s an example of that process in action:

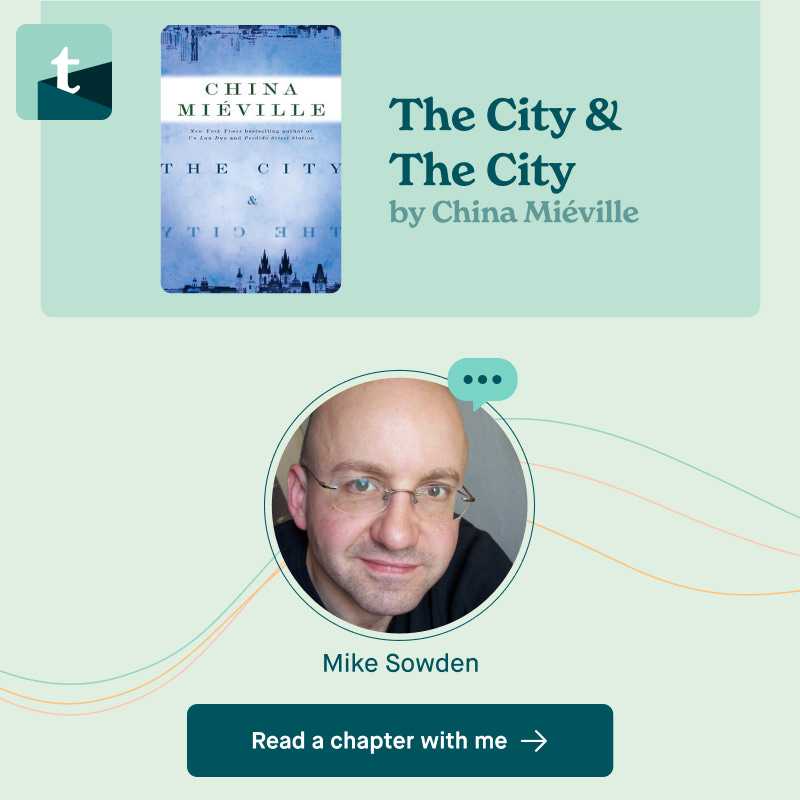

Click the below image (and then click on “Start Reading”), and you’ll go through to the first chapter of one of my favourite novels, which partly inspired me to start writing Everything Is Amazing…

(I actually wrote about The City & The City in the very first edition of EiA, way back in 2021.)

However! For copyrighted texts like On Looking and The City & The City, I obviously can’t put up more than an excerpt on Threadable, because that falls outside the realm of Fair Use and well into the realm of Completely Unfair Use Where Alexandra Horowitz & China Miéville Can’t Afford To Keep Writing Beautiful Books Anymore - which is the direct opposite of what I’m trying to achieve with this book club.

So, as an attempt to keep using Threadable for this Big Amazing Read, I tried putting my own discussion notes for On Looking on there! Aaaaand it’s not really designed for that.

Oops. 🤦

Some of you emailed me to let me know you were confused about this approach. Understandably so! On reflection, it’s an unhelpfully messy way to do things - so I've now abandoned it.

Therefore: from now on, I’m publishing my own discussion notes for On Looking, chapter by chapter, in newsletters like this one, which I’ll send out to all of you.

My notes on the first two chapters are below.

(Technically speaking we’re currently in week 8 of the read, so I have a bit of catching up to do here. Please bear with me.)

If you’re taking part in the read-through and you want to share your own thoughts with me and everyone else, please leap into the comments in this newsletter - I’d love to hear what you think of these chapters, and also the book as a whole.

Cheers!

M

Notes on “On Looking” - Chapter 1: Muchness

Alexandra Horowitz goes for her first walk round the block in the company of her nineteen-month-old son.

(Header quote: “You can observe a lot by watching.” - Yogi Berra)

Speaking as someone who doesn’t have kids, every time I read this chapter (I must have done so a dozen times over the last decade) I enjoy it even more. How often in life can we childless folk get this parent’s-eye perspective on a toddler’s experience of the world around them? Maybe I just need to read more books aimed at parents. But – there was so much here that made me realise how radical “growing up” is as a mindset, as a rigid adherence to a bunch of ideas overlaid on the sensual chaos of using our senses.

Take Horowitz’s focus on shapes, starting with triangles. When a child is learns the difference between how the world *looks* and how it *is*, they instinctively grasp things we take for granted, like perspective, and parallax (the slower movement of more distant objects tipping us off about how they’re further away).

Kids also learn that shapes mean something – specifically, they mean we’re looking at known objects from different angles. This is quite the trick, and it still baffles us adults occasionally – I found myself amazed a few months ago when watching a Scottish ferry come into dock, first pointing directly at me on the shore so all I could see was the prow of the ship, but then swinging sideways and seemingly expanding, stretching out impossibly until it was far longer than it first looked. My brain “knew” what it was looking at, but that didn’t stop another part of it thinking “wow, I had no idea that ferry was so big!”. A difference in viewing angles can still surprise.

This isn’t a skill that comes naturally to us. We have to learn it, and we do so in those first few intense years of learning, the “crash course in sensory experience” in Horowitz’s words. Then we can interpret what we see with no hesitation, no lag – it’s not “THIS shape means THAT thing”, it’s instantly “ah, it’s THAT thing.”

But it’s a fruitful, even an exciting thing to try to reverse this process, and here’s one way to do it: close one eye.

By removing binocular vision and depth perception, it’s easier to imagine flattening a scene in front of you so it’s nothing but a two-dimensional canvas of coloured shapes. This is the painter’s and graphic designer’s skill – and the toddler’s first sight of an overwhelming world of light and shadow and movement and confusedly arrested attention.

The fact that nearly all kids end up being perceptually wired up in very similar ways – able to interpret a shoe on top of a bag of trash as exactly that, rather than a confusion of images that looks different from every angle – is astonishing, and I feel that wonder every time I reread this chapter.

Another bit I loved, which startled me:

“Information taken in by the eyes might be processed in any part of the brain – it could be the visual cortex, leading to an inchoate “seeing”; but it could also be the motor cortex, leading to a leg kicking; or the auditory cortex, in which case a nearby teddy bear may be experienced as a bang, or a ringing, or a whisper. There is good reason to believe that this kind of synesthesia is the normal experience for adults.”

I’ve often seen babies kicking their legs or waving their arms wildly when they see something new, or when their eyes fix on your face, and I always thought it was just general, uncoordinated excitement (the type I have as an adult). But realising it might be part of their process of “seeing” because their brain hasn’t finished wiring itself up in the standard way – that’s mind-blowing and thought-provoking, because, what capacity do we retain for *re*wiring ourselves, for making new connections in that “brothy gap between neurons”, even if it’s in a tiny way and just temporarily?

This reminds me of the famous experiment by psychologist George Stratton – he wore spectacles that inverted his vision, so the world looked upside-down. But after 8 presumably hellish days of it, his visual system adjusted and he was able to interact with the world normally again – until he took the glasses off, at which point everything was once again upside-down.

This is a possibly a simplification, because maybe his brain didn’t make everything look “upright” after those 8 days, it just learned to interpret an upside-down world – but it does show the astonishing power of our minds to adjust to radical new ways of experiencing, including seeing.

(Further experiments in the 20th Century, including by Professor Theodor Erismann and Ivo Kohler of the University of Innsbruck, found that this effect also works with glasses that flip vision left-to-right – although one subject vomited almost continuously for the first day he did it, so, yeah. I’ll pass.)

In Horowitz’s view, this is what the biological underpinning of attention might be: a “script” our brain follows, this-then-that-then-this-equals-”paying attention”. In which case, can we willingly edit that script, or (to get paranoid about the effect of the worst of all our fancy new technology) can it be edited for us without our consent?

“It was not a lovely part of the building. My son had noticed it. He was blessed with the ability to admire the unlovely. Or, I should say, he was blessed with the inability to feel that there is a difference between lovely and un-.”

This is the start of my favourite part of the chapter and maybe the whole book.

Horowitz makes the point that as our visual vocabulary moves from simple shapes to objects and the relationships between them, we learn what is “uninteresting”, “ugly” and “boring”. Familiarity breeds contempt, but also so does learning how to see the world like your parents, as they teach you, consciously or otherwise, what is worth paying attention to, and what isn’t. Eventually this turns into “taste” (in the cultural sense) and other complicated concepts, but at its basic level, we stop paying attention to allegedly attention-unworthy things – like Horowitz being surprised at the amount of trash around her block in the Introduction.

Toddlers have no such preconceptions. Everything is a lesson, and therefore everything is worthy of study. Pebbles on the ground. Dump trucks. Standpipes. It’s all amazing!

This is a skill some adults have to relearn: scientists, journalists, private detectives. To see even the ordinary as extraordinary and therefore worth looking at properly.

(This is partly why my newsletter is called Everything Is Amazing. I want to see the world that way too.)

“Someday, he will appreciate others’ perspectives, have an idea of their histories, their motivations, their choices, their moods, their own childhood learning these kinds of things. He will be sympathetic. He will be kind, and, I hope, polite. But not yet. He is quietly but plainly rude.”

Who doesn’t love this about kids (apart from the easily offended)? The ability to blurt out the thing all the adults are pointedly avoiding saying. As chaotic as it can be, I love how kids get a pass for saying these things because, hey, they don’t know better.

But sometimes, maybe they do – they haven’t learned that honesty is sometimes an undiplomatic trait in social circles, which can often be another case of adults acting foolishly under the guise of being “sophisticated”…

Maybe sometimes, kids really do have the right idea, and it’d be nice to remind ourselves of it.

Notes on “On Looking” - Chapter 2: Minerals and Biomass

Alexandra Horowitz goes urban rock-hunting in the company of geologist Sidney Horenstein.

(Header quote: “To find new things, take the path you took yesterday.” - John Burroughs)

Oh, to be able to go for a walk like this one, in the company of a supremely knowledgeable rock specialist who can tell you everything you’d want to know about the stone under your feet and the artificial, unnaturally-shaped human-made outcrops that make up a modern city.

“Don’t be fooled, though, by the casual cap and easy manner. Horenstein is a man who knows vastly more about the past, oh, four hundred million years of the city than you do, and he is about to gently let you in on how little you know.”

That’s important too: the word “kindly”. Nobody wants an arrogant windbag as a guide. And according to his New York Times obituary from 2008, he was much-loved as a human being as well as an expert geologist.

He’s quick to puncture Horowitz’s ideas about how “unnatural” the city landscape is around them. Asphalt is minerals and biomass. Hexagonal paving stones reflect the natural shapes of cooled basalt columns. Almost everything may be the product of human engineering, but what we engineer *with* is almost always the raw stuff of the Earth – and it can tell us a story.

“While I was mulling over the effects people have on rocks, Horenstein brought me back to considering the effects rocks have on people.”

This is such an important perspective shift. We aren’t just parasitical plunderers of the natural resources of the world – we’re deeply affected by them, so when we don’t work in harmony with them, we suffer. We already know this is true in relation to trees and water and animal life – but rocks?

Yes, of course! I wrote a season of my newsletter about this so I’m biased, but – aesthetically, there is obviously a difference between how rotting concrete will make you feel vs pristine White Marble, but the natural qualities of rocks can also affect the way they retain heat, protect against or absorb moisture, move air around – all of it.

(For example: concrete, the world’s most popular building material, is incredibly dangerous in cities for the way it absorbs and them emits heat, especially in full sunlight, and a lot will need to be done and a lot of money spent to mitigate this. Compare this with the “cold-absorptive properties” of the stone Horowitz encounters with Horenstein.)

I loved the perspective-shift that Horenstein gave Horowitz when they were strolling through Central Park – and I had to laugh at the “Yikes!” when she lapsed into geological jargon. But it really is like a language that you learn! Once you know what a schist is, you understand how it came to be, and *that* tells you a lot of information very economically about what the landscape you’re in looked like millions of years ago. Jargon can be so intimidating – but it’s not pointlessly so. It’s a doorway into a deeper level of meaning, where everyday words are the long way round.

(Well, okay – sometimes it is. Jargon is jargon.)

“The difference is that the scene is meaningful to the chess master but not to the novice. To the expert, every piece relates to the others, and every arrangement of pieces on a board relates to previous boards the player has seen or made. They become as familiar as the faces of friends.”

This section touches on something I’ve recently been learning about with regards to human memory. In experiments, Grand Master chess players have shown they’re incredibly good at remembering “real” chess boards – ie. from real games that are or were taking place – and no better than a complete novice at remembering a random scatter of chess pieces on a board in a “fake” way that could never happen in a real game. What they’re seeing, and recalling, is a pattern, like the features on a human face. Jumble that pattern up artificially and it’s unmemorable and doesn’t grab our attention except in its startling randomness.

(Whatever your speciality is in life, I bet you have a refined version of this ability too. We are all advanced pattern-seers, just in different ways.)

“The stone has multiple stories to tell us, because it has multiple lives.”

This is the fascinating transition zone from geology to archaeology, to where humans come along and leave their own marks in and around rock. I loved learning about “feathering” here to break up rock, which leaves the stylistic fingerprints of the stone mason who did the work. This “whirlwind tour through eons” doesn’t have to be at the expense of the humans who made and influenced these buildings – it includes them in the overall detective work, because we are all part of the ongoing story of that stone’s history. (I think this every time I run a hand along a stone face, becoming yet another erosive force in its long journey to becoming sand or dust.)

Such a fun read, all this. I remembered this chapter when I recently started reading Helen Gordon’s Notes From Deep Time (an excerpt from this book is one of my previous reads on Threadable, here – go find it to take a walk through London in much the same way Horowitz and Horenstein do through New York).

To re-see the canyons of a city in this new, living-history sort of way must be such a treat when you’re in the company of someone that knowledgeable and curious.

What did you think about the ideas in these chapters? How are you finding the rest of the book? Give me your thoughts below! Thank you.

Thanks for the audible tip! I have been not starting the actual book and today listened to the first 2 chapters on slow hot walks to and from work. Loving it ❤️

SO GOOD! Your writing and your determined pursuit of wonder is so inspiring. Thank you