5 Wild, Weird Ideas From Science Fiction

Dreamy robots, sexless worlds, a runaway train to the end of the universe, and more.

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, wonder and why it’s okay to not have all the answers.

First, a quick and embarrassing update on a previous newsletter.

A while back I wrote about the amazing blue morpho butterfly, with its shiny, shiny coat of structural colour (that's a colour produced by tiny surface structures interacting with light, not by coloured pigments - think the sheen of a pearl.)

While writing it, I thought to myself, "Damn, I'd love to see one of those someday. What a gorgeous colour."

More fool me, because what I didn't realise is there has been one outside my flat for the last year.

It’s in the entrance leading up to my second-floor apartment here in Scotland, as decorated by my landlord:

What kind of idiot misses something that obvious?

Answer: me. The Me kind of idiot, that’s what.

I haven’t been able to ask my landlord yet, so I have no idea how this taxidermized butterfly (usually found in the tropical forests of Latin America) ended up here. And I also don’t know how I could have walked past it every single day since I moved into this flat without noticing it!

Curiosity FAIL. 🤦

Secondly: there are now well over 350 of us reading & discussing the introduction to Alexandra Horowitz’s On Looking over on Threadable.

(Thank you! What a really great start to EiA’s first Big Amazing Read.)

If you want to join them, click below for all the details you’ll need:

For today’s edition of this newsletter, exclusively for paid subscribers: let’s play with some mad science that would be guaranteed to change everything.

I started this newsletter in early 2021 with a piece of modern speculative fiction: China Miéville’s 2009 novel The City & the City, a novel that blew my tiny mind on almost every page. It helped me set the tone for this newsletter - to chase those “wow!” moments as far as they’ll go, in the hope of learning something truly remarkable that I never knew before.

Science fiction’s always done that for me. I’ve been a sci-fi nerd since my early teens - but one that loved big head-expanding ideas a lot more than lightsaber battles and Klingons on the starboard bow.

(That said, when I was a kid I had this metal & ceramic Starship Enterprise - and it was confiscated after I shot my Mum in the eye with a photon torpedo. Not my proudest moment, but life went on.)

Sci-fi is where big thinkers go to play with their ideas. Well, okay, sometimes it is, but the people whose work I loved reading the most? Them for sure. They treated science fiction with curiosity, wonder and respect. Not just as a grimly violent backdrop where future people were monstrously crappy to each other in the bad old ways, just with fancy new technology. Not just another war or depressingly brutal battle of wills except in space, but something brand new that required the future in order to exist. Something bold and strange and different.

That’s the science fiction I love, and if you’re reading this newsletter, I reckon you’d get a kick from it too.

Here are five big ideas about possible, unlikely or wildly improbable futures that have captured my imagination and really got me thinking.

1. What If Robots End Up Even *More* Human?

With every discussion of the ramifications of artificial intelligence software, we eventually get to all those Terminator scenarios. What if things turn stabby? What if the massive imperfections of our messy, irrational and wildly short-sighted hominid species prove unpalatable to a powerful A.I., and it decides that Agent Smith in The Matrix was right - we’re a virus destined to be stamped out?

For clarity: when I say “A.I." I don’t mean the current crop of tools that have proved so controversial, so resource-wasteful and often such a parasitical blight for creators of all kinds. (For a clear-sighted take on the genuinely practical uses of these tools, I’d recommend Professor Ethan Mollick’s work.) No - this is about truly self-aware machines, capable of independent and original thought: Artificial General Intelligence, to use the correct jargon. We’re definitely not there yet.

My biggest beef with AGI doomsday scenarios is the self-absorption: the automatic assumption that any advanced non-human intelligence is going to have exactly the same fixations with power, status and ownership (and all their by-products, including warfare) that so many humans do.

It’s like an extension of what Lord Acton famously said in the 19th Century: power corrupts, so absolute power corrupts absolutely, so hey, the same is true for intelligence, right?

Well - I can’t answer that, being a fairly average-brained human, but my imagination definitely says “really? Can’t we even consider the possibility that this is thinking way, way, way too narrowly, based on exactly one example of intelligence in the known universe?”

That side of things is hard to speculate about - even, I’d imagine, for professional sci-fi authors.

(But one thought refuses to dislodge itself from my head: if there was consciousness that was vastly more intelligent than humans, and it recognised that inequality and injustice fuel human conflict and that warfare seems to be the single most wasteful use of limited natural resources in a finite universe, wouldn’t it actually want to do the opposite of enslaving and killing everyone?)

But then there’s artificial intelligence that goes in the other direction: towards a learned morality we’d recognise as intensely, uncomfortably human.

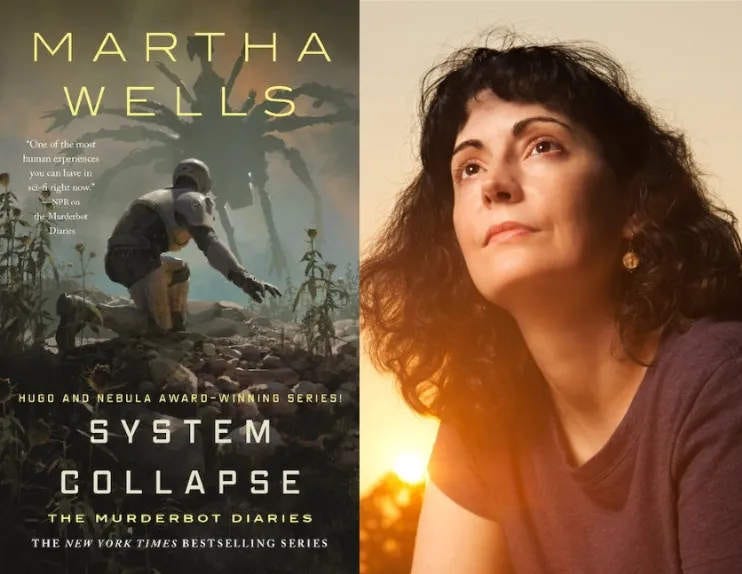

Enter Murderbot, the protagonist of a series of novellas, novels and short stories by Martha Wells that will soon be adapted by Apple TV+.

Murderbot is a SecUnit - a cyborg (part-machine, part-biological) created by humans to act as advanced security guards. Not by choice, of course: under normal circumstances, a SecUnit’s intelligence would be fully under human control.

In a recent interview with New Scientist, Wells explains how this works:

“In the world of All Systems Red [the first novella in the series], humans control their sentient constructs with governor modules that punish any attempt to disobey orders with pain or death. When Murderbot hacks its governor module, it becomes essentially free of human control. Humans assume that SecUnits who are not under the complete control of a governor module are going to immediately go on a killing rampage.

This belief has more to do with guilt than any other factor. The human enslavers know on some level that treating the sentient constructs as disposable objects, useful tools that can be discarded, is wrong; they know if it were done to them, they would be filled with rage and want vengeance for the terrible things they had suffered.”

Murderbot does indeed recognise all this, but wants something different from its newly-hacked freedom. It doesn’t want retribution. It wants drama. Specifically: soap operas.

After hacking its access interfaces, it realises it can tap into all the human entertainment feeds, the Netflixes and iPlayers of the future. And so it downloads hundreds of episodes of TV shows, and gets addicted to them.

Why do we consume entertainment? Yes, as a distraction from the boring grind of the day and the worst horrors of the news - but also as part of a vast “user manual” in human behaviour, with nobody in control but everyone trying to trigger the biggest emotions and win the most eyeballs. What if an A.I. consumed all the emotional lessons of entertainment and learned how to not just be human, but that exaggerated, heightened, “here’s the moral of this tale” type of it you only get from stories?

As Wells says:

“The dramas, mysteries, adventures and other shows that it watches also give it context for human behaviour, and for understanding its own emotions. The security contracts that it has worked at mining colonies, supervising indentured workers, only show it humans at their worst: angry, terrified, resentful, trapped and hurting each other. And when given the opportunity, the humans also hurt the constructs that are there to keep them under control and working for corporations that see their employees as only slightly less discardable than the constructs and bots.

The shows that Murderbot watches also teach it about the wider world it has never been a part of before, as well as how to navigate that world. The entertainment Murderbot becomes addicted to is a large part of what makes it possible to turn the mental escape from reality into a bid for real freedom.”

So, extending this into our world - what if robots of the future actually became better dreamers than most of the humans around them? What if they ‘grew up’ (if that’s the phrase) on exactly the kind of Art that allows us to flourish as well-rounded humans in all the ways that matter - but were also furnished with intellectual abilities that could take those smart, beautiful and deeply empathetic ideas forward in a way mere humans never could?

Writers of all kinds, please get writing those stories. Your future students are waiting.