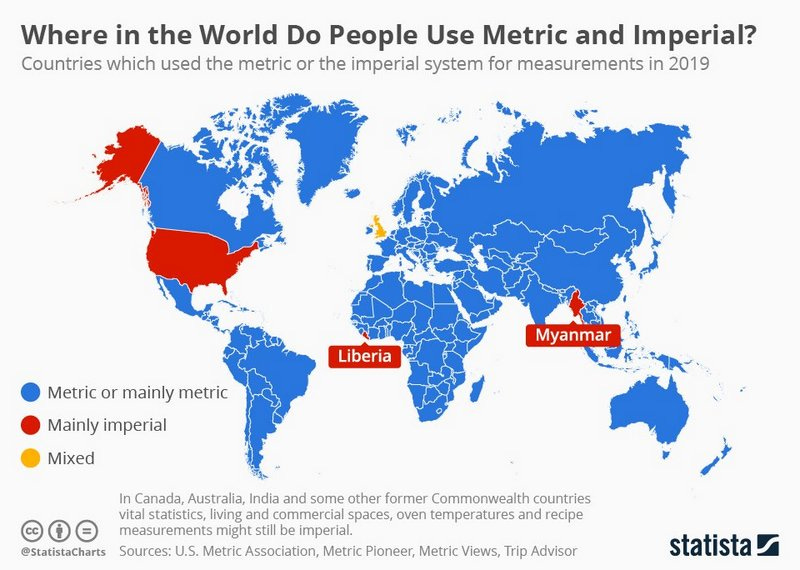

Why Stay Imperial In A World Gone Metric?

AKA. What does the United States know that the rest of us have forgotten?

Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about the science, wonder and weirdness of curiosity.

The newsletter’s currently on a break after wrapping up the last season - so in place of new editions, I’m giving you a whistle-stop tour of some of its most popular posts, so you can get a taste of some of EiA’s many flavours.

This one is from season 2, way back in 2021, when we were looking at maps - and in this edition, we’re using one to ask “hey, what on earth is the United States playing at here?”

So many questions. Hey, is Metric really that popular?

And what made the U.S., Liberia and Myanmar join forces like that?

And oh look, us tediously exceptionalist UK folk are at it again with our special “Mixed” status.

There’s an awful lot to unpack here.

For starters, don’t be fooled by that splash of yellow. Britain should really be a dark shade of green - ie. a little yellow, mixed with a lot of blue. We Brits may regularly use inches, ounces, miles and pounds in everyday life, but we’ve officially been Metric since 1965.

(It’s interesting, and by that I mean rather annoying, how often non-British news makes a tangle of this. Take this story from 1999 about the unfortunate Imperial-to-Metric conversion error that led to the loss of NASA’s $125 million Mars Climate Orbiter. Note how “Imperial” is called “English” in that story. What they really mean is US Customary, the version of Imperial that the United States uses today, which is actually based on the units of measurement England used before we adopted Imperial in 1824. If you have to write “English” here, put the word “Old” in front of it, please.)

So I’m from a culture that officially embraces Metric - and after a lifetime of loyalty to it, I took its importance for granted, and didn’t consider the value of alternatives. I mean, Metric works best! Why consider anything else? In other words: curiosity FAIL.

When I realised this, I started my reading. And now…

OK, America. Now I understand why 5% of the world’s population won’t give up on Imperial, why the United States actually hasn’t lost its mind (not on this topic, anyway) - and what we’ll all lose if we fully embrace Metric.

Let’s take a huge step back and see how we got here.

It’s 1790, and France is an immeasurable mess.

Firstly, there’s the small matter of the entire country having just violently turned itself inside-out, in what we now call the French Revolution.

(We modern folk often assign this famous socio-political convulsion to 1789, but really, it’s best thought of as “most of the 1790s”. For example, the infamous ‘Reign of Terror’, that savage parade of executions that ignores the tedious bother of establishing anyone’s actual guilt using facts and the law? That only ends in 1794.)

And secondly, it’s just so hard to measure anything.

The problem is getting everyone to agree. France at this time has around 800 different measures being used in over 250,000 (!) different ways, many of them delightfully specific (for example, a quantity of arable land was sometimes measured in “days”, as in, how many days it’d take for a single peasant to farm it). So far, so practical.

But then you walk a few miles to the next village, or have to answer to the regional tax-man, and suddenly you had to explain what your “30 peasant-days of land” actually meant in a language they understood - and it all falls apart. A quarter of a million systems, all needing to be converted into each other without the help of a calculator. Merde.

This was a source of great embarrassment for a new government thrown together on the rationalist principles of the Enlightenment. Something had to be done. Quickly.

In 1790, a panel of leading French scientists thrashed out a plan. This new measuring system would base itself upon the unchanging laws of Nature, using a decimal system that would make scaling calculations easy.

One of these new units? The metre, from the Greek verb μετρέω, “to measure.” The scientists decided it should be based on the size of the Earth: more specifically, one-ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator, on the meridian that ran through the middle of Paris.

At some point - perhaps after this definition was decided upon - someone pointed out that since nobody really knew how big any of these distances were (using any units of measurement), some poor, wretched souls would have to go forth into revolutionary Europe and take measurements by hand.

This awful task was assigned to two astronomers: Pierre Méchain was despatched to Barcelona, while Jean-Baptiste Delambre went to Dunkirk. Their one-year mission: to seek out brave new heights by climbing extremely tall things, so they could take enough horizon-based measurements to extrapolate the Pole to Equator curve that would determine the length of a metre.

Well, they thought it would take a year. It actually took seven - and became a true adventure. If anything, that’s an understatement:

Along the way, Delambre and Méchain would be imprisoned, injured, almost executed, scorched, frozen, mistaken for sorcerers and spies, fired, reinstated, vilified, celebrated and then vilified again. For Méchain, the task with which he had been charged would lead eventually to his death.

Somewhere near Barcelona, at the very start of his triangulations, Méchain made a small error of computation. Once this error had entered his system, it was impossible to eradicate it. For years the knowledge of this error haunted Méchain - the thought that he alone had managed to falsify what was intended to become 'the fundamental scientific value, the measure which would for ever more serve as the foundation for all scientific and commercial exchange'. In 1804, suffering from acute depression apparently brought on by guilt, Méchain returned to the Valencian coast to try to atone for his error. There he caught malaria and died.

(From Robert MacFarlane’s Guardian review of Ken Alder’s The Measure Of All Things: The Seven Year Odyssey That Transformed The World.)

But by 1799, the new system was ready to roll out - and it was glorious. To convert between units on the same scale, you just added zeroes or moved the decimal point left or right. In comparison with everything it replaced, it was so simple to calculate it was like magic.

Except, there was one problem. A biggie.

Let’s say your government completely loses its mind and hires me (hi!) to create a new system of length measurement, as follows:

1 Sowden (length) = 50 miniSowdens = 200 microSowdens

You’re a bit confused by all this, so you ask a govt official how big a Sowden is.

“Oh, it’s 50 miniSowdens.”

Yes, but how big is that?

“200 microSowdens!”

Uh….

“Ohh. Right, I see your point. Well, it’s taken from Nature! A Sowden is one eleventy-billionth of the distance from the geographical centre of Yorkshire to the Sun!”

Sigh.

A new system of measurement is only workable if someone has a pragmatic, hands-on frame of reference for it - and Metric, while fantastically precise in principle, turned out to be really damn hard to explain to a French tradesperson asking why the system they’d used all their life without any bother isn’t considered “practical” anymore.

The solution? Install a new ruler.

No, the other kind.

Alongside thousands of educational pamphlets, public lectures and “educational games” designed by government-sponsored private enterprises, Paris briefly became the wooden-ruler-making capital of the world.

Or at least it would have been, if it could keep up with demand. Despite heavy investment from the government, one month after the launch of Metric, just 25,000 metre rulers had been manufactured - far short of the 500,000 needed just within Paris alone.

You can guess how all this went down with the wider population of France.

By 1812, newly-installed French Emperor Napoleon had had enough. He’d sent police officers to marketplaces to enforce the Metric system. He’d spent a big chunk of the fledgling Empire’s cash reserves on education and pro-Metric initiatives. And in response, the French dug their heels in. Non, Monsieur Emperor. Vive l'Impériale!

So he gave up. His “Customary Measures” legislation of 1812, restricted to use in commerce (ie. those pesky marketplaces), rolled back Metric and introduced a series of messy compromises that tried to keep the bulk of the people happy, so Napoleon could focus his full energy on unsuccessfully invading Russia.

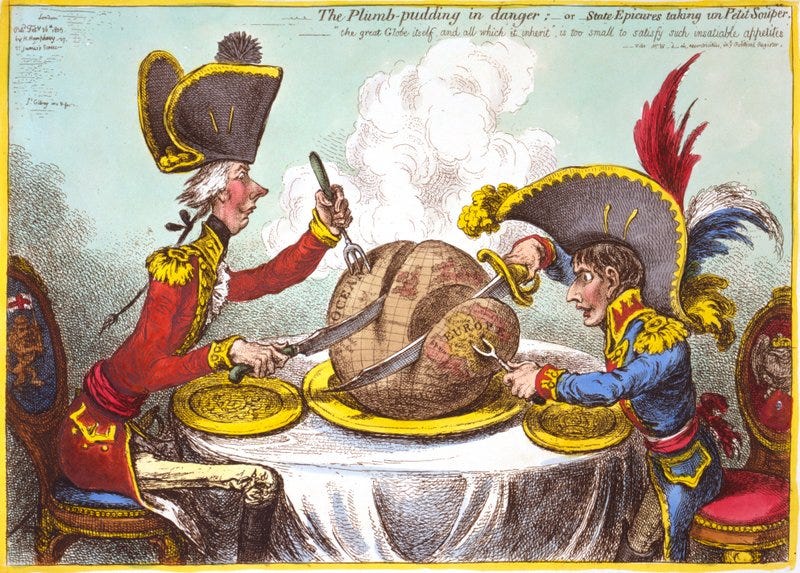

The British, of course, took every opportunity to ridicule Napoleon. Like how they intercepted his increasingly tortured-sounding love letters to his wife and plastered them gleefully all over the London newspapers.

And of course there were the cartoons:

Ah yes. Napoleon Bonaparte: history’s most famous Vertically Challenged Person.

There is of course nothing clever about ridiculing people’s height. This is especially true when it’s accidental and you’re emailing an editor who might publish your writing some day:

But back in 19th-Century England, heightist jokes were all the rage. How dare that tiny French nitwit strut around Europe so aggressively! We should go over and give that miniscule popinjay a damn good thrashing! (Haw haw.)

Yet again, this was an illustration of the kind of problem Metric was invented to fix. After British cartoonists learned through diplomats and spies that Napoleon was 5 feet and 2 inches tall, they saw it as a new way to poke fun at the nation’s sworn enemy - and started depicting him as a tiny, tiny man.

Unfortunately, they missed something important. The traditional French Inch, brought back into use in 1812, was actually longer than the British one. Napoleon’s real height? Somewhere between 5 ft 5 and 5 ft 7, which was more or less the average height for a Frenchman at that time…and also an Englishman, too. J’accuse, rostbif.

Sure, Napoleon may have been a monster who perverted the ideals of the new Republic into a greedy, dictatorial parody of itself, ultimately leaving France shrunken and bankrupt with millions of its citizens dead in his wake - but he wasn’t unusually short. Let’s give him that at least.

Metric was reinstated in France in 1840, just in time for its Industrial Revolution - but in the words of Ken Alder, “it took a span of roughly 100 years before almost all French people started using it.”

It’s easy to leap to some narrow-minded assumptions here, like I did when I first learned the United States prefers using Imperial. (For any fellow Brits feeling a similar tendency towards smugness here: let’s not forget that the U.S. was the first country in the world to adopt a decimal-based currency, all the way back in 1792, when we Brits were still faffing around with shillings, guineas, farthings and the like.)

But people aren’t stupid. Examine the growth-cycle of a tradition that’s endured for centuries, and somewhere in there you’ll usually find a sensible, logical reason it got lodged in people’s brains in the first place. And it’s often about efficiency. Nobody wants to make life harder for themselves.

So is Metric really easier to use?

The standard way of answering this is equating “easy” with “your ability to calculate with it.” This is where Metric has everything else beat. A base 10 system, and you’ve got ten fingers to count with? Game, set, match.

But as we’ve seen, calculating is only part of using a measuring system. You need to know how big those measurements are - ideally without using something else within the same system as a reference. And while Metric measurements pride themselves on copying Nature, they do so in a way that you often can’t see in Nature. Not directly, not with your own eyes, not without help.

And horrifyingly, some of Metric was just plain made up.

Take the kilogram, originally designed to be the weight of exactly 1,000 cubic centimetres of water. An issue to consider here: the weight of “water” is not a fixed thing - its weight varies with different temperatures and substances dissolved in it, meaning there are many, many “waters”. Plenty of room for arguments that would slow the whole process down. So the scientists cheated: they made a kilo, in the form of a platinum-iridium alloy cylinder (nicknamed “Le Grand K.”) and told everyone to compare their weights against it.

Then in 1989, someone discovered this prototype now weighed a bit less than it should. Somewhere along the way, the bar had lost 50 micrograms, enough to render it useless for modern levels of scientific accuracy.

So everyone got to work again, looking for a way to tie a kilogram with essential properties of the natural world (described as “the second most difficult experiment in the whole world,” behind the search for the Higgs Boson particle).

The new definition of a kilo now relies on three fundamental constants:

the speed of light

the cesium atom’s natural microwave radiation

the Planck constant, used for measuring how atoms and other particles absorb and emit energy.

Phew. Job done?

Except…now a kilo is like the other Metric measurements: something you can’t see directly.

You can’t eyeball Planck’s constant.

You can’t see how fast light travels (hands up if when you were a kid you ever used a mirror to try to catch a glimpse of the back of your head by turning around really, really quickly).

All the nopes. It’s yet another abstract, invisible measurement for the everyday non-scientist. Is it really any wonder that Metric has taken so long to catch on?

So, turning to Imperial - with the caveat that “Imperial” is often what people call “everything that isn’t Metric” these days.

As a Brit, I think in Miles. (Always have, maybe always will.) The Mile comes from the Latin word for thousand, and means a thousand paces. As someone reminded me on Twitter, a pace is not the same as a step/stride - but it’s clearly a measurement invented by someone walking along at a fair old lick. A measurement wrought of human experience.

But…that’s English Miles. There are others: Scots, Welsh, Irish, German, Portuguese, Scandinavian, Italian, Chinese, Ottoman, Saxon, Roman, Arabic, nautical…and many more. The Ye Olde English type, though, is made of 5,280 feet (which becomes a deeply inelegant 1,609.344 metres.)

A Foot is - a foot. Right there in the name. Imprecisely but workably, that’s how long.

An Inch is the width of your thumb - or what you do with your fingers when someone says "what's an inch?" 😄

Go back further and you find it’s all about practical issues:

The Cubit (the ancient length measurement, not the currency of Battlestar Galactica) is the distance from your elbow to the tip of your middle finger. It’s virtually extinct now - except in the hedgelaying industry. Hang in there, guys, we’re counting on you.

The Ell is an old unit for measuring cloth, and was defined as the length of the average adult arm: the name came from the Latin for arm, ulnia.

An Oxgang or Bovate, used in pre-Industrial Scotland and England, was the amount of land that could be ploughed by one ox during a single season (usually around 15-20 acres).

Pennylands, Farthinglands, Ouncelands, Halfpennylands and Groatlands were Scottish terms for areas measured by how much taxation was due on them…

Yes, all of these lack precision, so they’re useless for modern science, and would be incredibly dangerous if used for engineering purposes. But they also tell a story of people’s relationship with the space they moved through. A lexis of movement - perhaps in a similar fashion to the language of landscape that writer Robert MacFarlane has done so much to retrieve.

This is why I’m on the fence about Imperial now. There’s no question that Metric is necessary as a standardised, exact form used to make cars that don’t shake themselves to bits, planes that don’t fall out the sky and spacecraft that can launch themselves to interplanetary targets with mindblowing accuracy.

But the versions of Imperial still being used by people in everyday life deserve their place in the world too.

Anyone brought up thinking and feeling temperature in Fahrenheit can tell us something different about how we can experience the world. Anyone cooking in pounds will be thinking about food a little differently (“well, it’s just 2 cups, isn’t it?”). All these things are tiny windows into new ways of seeing what we think we already know.

And I hope the same daily experience side is true about Metric - please, Metric-lovers, weigh in with a comment! But I know of only a few examples.

(When I’m packing my rucksack, I compare the weight of every item with a 1kg bag of sugar held in my other hand, so I can ‘guesstimate’ the weight of the whole thing as I go along.)

Maybe it’s too soon to ask a Brit about how Metric feels. Ask us again a hundred years from now.

In summary, dear friends across the Atlantic: I apologise. There’s nothing terribly “backwards” about your non-Metric measurements. I’m done poking fun at them, and I hope we can get back to arguing about more pressing issues, like your regrettable habit of dropping vowels for no reason whatsoever, or why you should say “tomato ketchup” for accuracy’s sake because there are other types (even though they’re vanishingly rare).

Good lord. You didn’t think all this meant we agreed on everything, did you?

Oh, America.

BONUS: this now-legendary Saturday Night Live sketch, which ran after I first published this newsletter:

I hope you enjoyed that piece! (It was a really fun one to research and write.)

You might also enjoy some of my paid-subscriber-only posts (including a piece that uses lessons from modern behavioural psychology to keep you creatively moving forward across “the chasm of Ughhhh”.)

With that in mind - from now until mid-November, all paid subscriptions to Everything Is Amazing are 10% off.

You’ll get access to paywalled articles, to my upcoming non-fiction storytelling course. and you’ll get a personal ‘curiosity call’ to motivate you to chase your own nerdiness in a similar way.

You’ll also be helping this newsletter exist. It’s completely dependent on reader support - and since EiA recently became my fulltime job, so am I. In the most real of senses, you’re helping keep the lights on - but you’re also helping me grow this project, hunt a few stories in person and make this thing even weirder. That’s what you’d be investing in.

Click below to sign up with a 10% discount. Thank you so much!

Images: William Warby, Wikimedia Commons, Luis Quintero, Nil Castellvi, Frédéric Perez.