How To Survive The Graveyard Of Ships

"I have felt this feeling before on a mountain, or in battle, and I should have been warned."

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science and wonder.

Today: a nautical true story that would curdle anyone’s blood.

Let’s dive in.

“It was as different from an ordinary rough sea as a winter’s landscape is from a summer one, and the thing that impressed me most was that its general aspect was white…

Here and there, as a wave broke, I could see the flung spray caught and whirled upwards by the wind, which raced up the back of the wave, just like a whirl of wind-driven sand in the desert. I had seen it before, but this moving surface, driving low across a sea all lined and furrowed with white, was something new to me, and something frightening, and I felt exhilarated with the atmosphere of strife. I have felt this feeling before on a mountain, or in battle, and I should have been warned. It is apt to mean trouble.”

It’s February 1959, and Miles & Beryl Smeeton, accompanied by their friend John, are steering into some of the most violent seas in the world.

It’s nearly 2 months since they departed Melbourne in their two-masted sailboat Tzu Hang, following the eastward route of the 19th-Century merchant clippers (below).

For weeks they’ve been riding the Roaring Forties - the powerful band of winds wrapping the Southern Hemisphere between the latitudes of 40° and 50° south - and they’re now preparing to dip into the even more thrilling/nightmarish Furious Fifties, to get enough southerly latitude to clear Cape Horn at the tip of South America.

By today’s standards, Tzu Hang is making sluggish progress - about a hundred nautical miles a day, compared to the upwards of five hundred miles that modern sailors can sail in the same time.

Below the deck, all is snug and homely. They have a portable stove pumping out heat when needed, they have books or piles of knitting or the England vs Ireland rugby results on the radio to fill their rare idle moments, their breakfasts are suitably lavish to meet the energy requirements of fighting seas as big as these, and the Smeeton’s blue-tailed Siamese cat, Pwe, is comfortably curled up by the fire.

If like me you’ve never been in fast-moving seas like these, you’ll be imagining the Hollywood idea of a small boat riding high waves, both approaching each other from opposite directions, and then *whoosh* up and over we go to race down the other side and meet the next incoming wave.

But both Tzu Hang and the ocean current are moving in the same direction, with the sea moving much faster than the boat - so each wave bears down on the sailors from behind, tipping them forward like they’re facing the wrong way on a rollercoaster.

Despite these conditions (or perhaps because of them), spirits are high. After all, this is what they’re all here for, and why the Smeetons bought this ketch five years ago and learned to sail in it. The adventure is the thing! It might get a bit dicey, of course, but there’ll always be a way to muddle through, so, chin up.

With Beryl taking a shift at the tiller and John changing the film on his camera, Miles settles back into his bunk:

“My book was called Harry Black, and Harry Black was following up a wounded tiger, but I never found out what happened to Harry Black and the tiger.”

So far in this atmosphere-obsessed season of Everything Is Amazing, I’ve written about extremely high stuff - like the balloonists (and occasionally paragliders) dragged up against their will to where the air’s too thin to breathe, or all the surprises hidden in the clouds and in our stratosphere.

But down here at ground level, we’re most used to the sky manifesting itself as the palpable movement of air we call wind.

It can be bracingly refreshing, especially after a few days of muggy stillness. It can be a tedious annoyance, especially if you’ve just had your hair done. It can even be a source of pathetically small-minded hilarity! I’m thinking of the time I was at university in York, sitting in a coffee-shop with a friend, both of us cackling as we watched pedestrians outside having their umbrellas thumped inside-out by a savage cross-wind coming up an intersecting street. (Big shout-out to the lady who at the first violent tug just calmly let hers go, and stood watching as it whirled Poppins-like into the sky.)

Then there’s the stuff we’re only just starting to learn, like whether there’s anything in the widespread belief that windy days make kids hyperactive (or adults downright crazy) - or how we can build artificial mountains to coax the wind into dumping all its rain in the most useful places.

Then there’s the recreational side of winds, where we form attachments with them strong enough to give them names.

Do you have a favourite wind?

If you’re a fellow Brit, it might be the Helm, blasting down the slopes of Cross Fell (the highest mountain in the Pennines) and often dragging a comet’s-tail of cloud behind it as it streams over the top.

Bafflingly, this is the UK’s only formally named wind - there are obviously plenty of others, especially up here in Scotland, but for some reason we haven’t bothered to name any of them? Weird.

In my case, the Helm is indeed my favourite wind. I’ve not yet had the pleasure of being flung to my knees by it, but I’ve seen it from afar (see above) on a day bitterly cold enough for my walking party to want to give it a wide berth.

The stories are legendary:

"Only a few years ago, bunches of hay were seen careering over Windermere at an estimated height of 2,000 ft, carried by the Helm Wind. Frequently haycocks [conical heaps of hay in fields] have been lifted bodily and then dropped into an adjoining field. Crops are sometimes swept away and trees uprooted. Cows and sheep are given a surprising momentum, pebbles roll along roads and paths as though pushed by some unseen hand, and, with the wind in the opposite direction, cyclists find it impossible to cycle downhill."

From "Anatomy Of The Helm Wind" by David Uttley.

I would write more about it here, but

of Weather With A Twist recently beat me to it:“The Helm is a rare and powerful downslope wind that sweeps off one of England’s tallest mountain peaks. As it barrels down a relatively narrow path, it creates a tremendous noise, louder than jet engines, and can cause significant damage. Though rare, it’s remarkably consistent - occurring a few times each year when the meteorological conditions align just right. It’s been observed for centuries, stopping armies and inspiring ghost stories alike.”

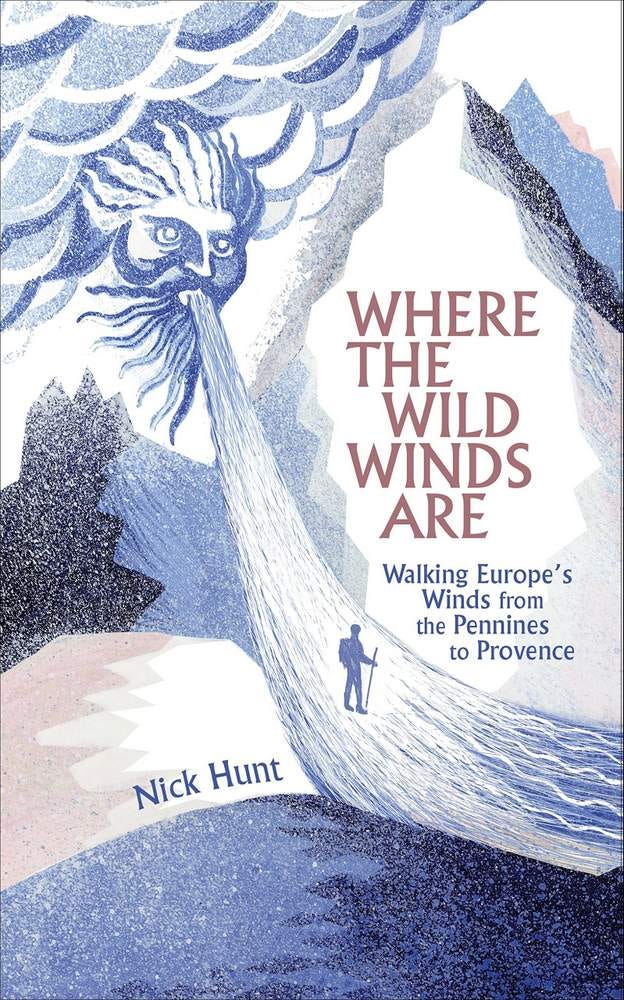

It’s also the starting-point of travel writer Nick Hunt’s marvellous odyssey across Europe in search of four of its most influential winds:

(You can grab Nick’s book here.)

But wind becomes far less charming when it strengthens and shows itself to be what it was all along - something with unimaginable power behind it that cannot be denied by any amount of our fancy modern technology.

Around Cape Horn, the wind accelerates to hurricane-force strength at least a couple of times a month. Otherwise, it’s merely murderously inhospitable: 60 to 80-knot winds combining with the gargantuan energy of two powerful ocean currents (the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and the Brazil Current) colliding with each other in a foaming chaos that can throw up some of the biggest waves found on our planet.

Into this terrible mix comes the kind of cold that can foul and unbalance ships with build-ups of ice - and the ever-present threat of smashing into an iceberg that’s been tossed north from the waters around Antarctica.

Over 800 ships have sunk in this stretch of ocean, claiming over 10,000 lives. It remains the most unpredictable, and consequently the most dangerous, sea route on our planet.

And if you’re in a small boat and something goes badly wrong out here - well, doesn’t bear thinking about.

(Pictured above: unidentified sailing ship in a storm around Cape Horn.)

“As I read, there was a sudden, sickening sense of disaster. I felt a great lurch and heel, and a thunder of sound filled my ears. I was conscious, in a terrified moment, of being driven into the front and side of my bunk with tremendous force. At the same time there was a tearing cracking sound, as if Tzu Hang was being ripped apart, and water burst solidly, raging into the cabin. There was darkness, black darkness, and pressure, and a feeling of being buried in a debris of boards, and I fought wildly to get out, thinking Tzu Hang had already gone. Then suddenly I was standing again, waist deep in water, and floorboards and cushions and mattresses and books were sloshing in wild confusion around me.”

On deck, Beryl could see it coming: a rogue wave, impossible to have predicted, “a great wall of water…so wide that she couldn’t see its flanks, so high and so steep that she knew Tzu Hang could not ride over it.”

This was her last visual image before impact - and the next thing she remembers is floating in the sea, her life-line broken, but when she turns, a miracle: the boat is there, just a few dozen yards away.

It’s lying low in the water, and both its masts are gone.

Clambering up on deck after having found John in one piece in the galley, Miles spots Beryl floating into view on the back of a wave. In his remarkably understated words:

“She looked unafraid, and I believe that she was smiling.

‘I’m alright, I’m alright,’ she shouted.

I understood her, although I could not hear the words, which were taken by the wind.”

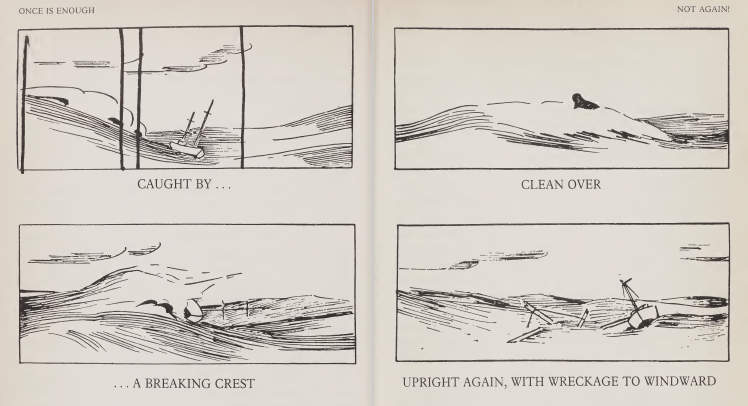

Soon she’s back on board, and all three survey the damage, which is profound. Tzu Hang had been pitchpoled - flipped end over end - by the rogue wave. Both masts are gone, leaving a 10-foot-wide hole in the deck. Both dinghies are gone, and so is the compass and the anchor.

John takes a look at the wreckage:

“This is it, you know, Miles.”

But then he finds his toolbox, and all three of them (with Beryl unable to do any lifting because her injured shoulder is seizing up) set to work bailing out water and patching the deck to stop more water coming in.

Tzu Hang is kept stable by the tangle of rigging and assorted wreckage in the water behind her working as a kind of sea-anchor - and a pathetic wail lets them know that Pwe, a “bedraggled rat of a cat”, has survived the disaster and is furiously demanding an explanation.

One exhausting day of backbreaking toil later, they’ve bailed enough water to confirm the hull hasn’t been holed, and they’re starting to make plans to erect a makeshift sail.

With hard work and a lot of luck, they might have a chance of fighting the current that’s sweeping them down towards the Horn - a passage they almost certainly wouldn’t survive in this state - beyond which point their only chance of landfall before Africa would be the Falkland islands (Islas Malvinas).

They now have around a hundred days of food & water to make it to the coast of Chile. Will it be enough?

There often comes a point when reading real-life adventure stories where you sit back and think, “Okay, no, NOPE, absolutely not, that’s the point where I’d go to pieces and go no further, also, you people are absolutely mad to have done this.”

I reached that point about a third of the way through Miles Smeeton’s Once Is Enough, and then spent the rest of the book marvelling in a horrified sort of way at the skill and determination and absolutely unhinged bloodymindedness of the Smeetons and their friend.

Not only did they make landfall in Chile, and not only did their insurance cover a full refit in Talcahuano, but Miles and Beryl then mentally tacked their way to a decision that you could interpret as admirably pragmatic, impressively self-aware or just plain bonkers:

“…whatever sort of wave had overtaken us, the result to Tzu Hang had made a deep impression on Beryl and me, and we both dreaded another storm in those waters. It was this fear of another big storm that made us feel we must face the danger again, but we didn’t speak about it to each other because we do not discuss our private fears, and to go and do something at our age because we were afraid of it seemed a little immature.”

And that is why, on December 26th 1957, with the boat once again riding through worsening seas, you have this passage:

“When the glass began to rise the wind would blow for a few hours, but this must be the worst of it now.

Almost as I thought this, Tzu Hang heeled steeply over, heeled over desperately into a raging blackness, and everything within me seemed to rebel against this fate.

All my mind was saying, “Oh no, not again! Not again!”

In roughly the same patch of ocean, in their run-up to entering the Straits of Magellan (their sole concession to ‘minimizing the risks’ this time round), they’ve once again capsized, breaking both masts:

It’s hard not to see in this deadly and terrifying situation a certain amount of high farce:

“ ‘By God, we’ve done it once and we’ll do it again!’ I said, and at once felt very stupid, as my detached and cynical self noted the heroics, and noted also that there was no one to hear, and that Beryl was already doing something about ensuring that we did do it again.”

Words fail me.

After another 30 pages outlining how they once again (!) safely brought the smashed hulk of Tzu Hang back to Chile, the final chapter of the increasingly inaccurately-named Once Is Enough includes the following wistful statement from Miles:

“If I was to take a small ship in another attempt to round Cape Horn, and I mean round Cape Horn in the old sailing route, I would have one built: [there follows a wish-list of features for this new boat].”

If you’re determined to pit yourself against the immensity of the sea, I guess it helps to be just as stubborn as it is.

Brigadier Miles Richard Smeeton, DSO, MBE, MC, born in Yorkshire, England in 1906, would go on to author ten books, including Because The Horn Is There (1970), an account of Miles and Beryl Smeeton’s successful attempt to sail round Cape Horn in 1968, accompanied by their cat, Pwe. In 1971 they founded the Cochrane Ecological Institute (CEI), dedicated to breeding endangered wildlife, which successfully reintroduced the swift fox back to North America. Beryl Smeeton died in 1979 and Miles died in 1988, from nothing more than old age.

Images: Fer Nando; James Eades; Miles Smeeton; Mike Sowden.

Amazing story. Only the British, or 😅!

Amazing!