How To Un-Discover An Island

"It only appeared on the maps because cartographers get embarrassed about big empty spaces.” - Terry Pratchett

Hello again! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about chasing your curiosity: how to do it, why to do it, all the stuff in your brain that gets in the way, and so on.

It’s also about trying to see the things hidden from you in full view, and about discovering what truly matters by randomly stumbling over it. There’s a lot going on here, maybe not all of it good. I hope that’s you warned.

(Hey, are you subscribed? You wouldn’t want to miss anything really horrible, would you?)

Okay. Today, a story about sleeping in the snow - and about the world’s most recently undiscovered island.

January 2015: Somewhere in Northern England

“The map ends here.”

That’s what the sign seems to be saying to me. A shrug made of wood. “Hell, *I* don’t know. Use your eyes, man.”

That’s poor advice for a gloomy late January day like this. Low cloud is descending (or is the light fading?) and the horizon creeps nearer every minute. A line of trees marks the edge of the known world: gunmetal-grey, looking even less hospitable than the featureless moorland all around. There’s snow on the ground, snow in the air, snow on the trees. Not the light, fluffy, kickabout kind. This is the deep-frozen, crystalline variety that forms a jagged crust and slices through the fingers of your gloves. The kind that hurts.

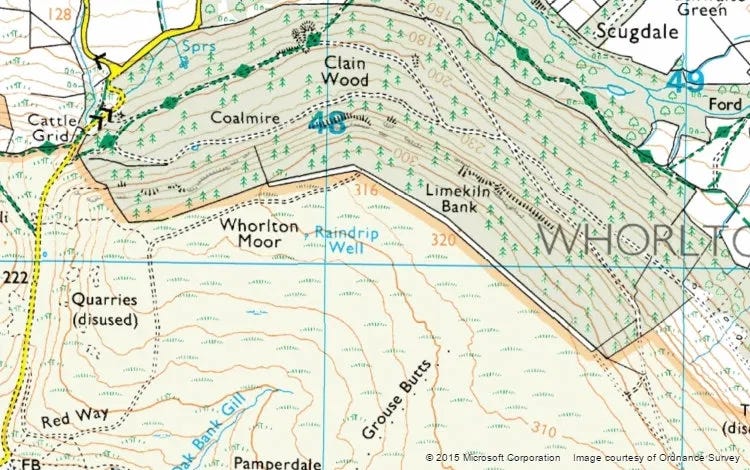

But it’s not like we should be worried. Our car is parked just half an hour behind us. The nearest town is a short drive beyond that. There’s no signal for either of our phones, but we have actual maps (OS Explorer OL26 North York Moors, Western area) and we roughly know where we are on them. Nothing about this should feel unnerving - but my hackles are still up.

“Probably best if we pitch up somewhere in those trees,” says Al confidently.

He knows what he’s doing, I tell myself. It’s his Landrover that got us here. He chose the spot. He’s an outdoorsy, seasoned field archaeologist with a bookcase of Cicerone guides and notebooks stuffed with accounts of previous outdoorsy adventures, many of them using the UK’s extensive network of remote bothies. If Al says this is safe, it’s safe. I mean, he wouldn’t be doing this if he didn’t know exactly…

“Ho ho ho. I’m not sure about this, Mike! Oh well. Guess we’re here now.”

Oh god.

It is impossible to walk off the map in Britain.

Yes, you can certainly get lost - as many unwary day-trippers discover each year. With the winning combination of poor conditions and reckless complacency, you can get into trouble anywhere, not just in the mountains (although in those especially, yes). But it’s all on the map, all of it. You may not know where you are, but hey, that’s your business, don’t go blaming Ordnance Survey for your failings as a navigator.

Or maybe you’d prefer to blame Google. (Or Bing.) Well, you’re on firmer ground there. They get their digital mapping data from over 7,300 satellites orbiting the planet, most owned by third parties who sell their images & scans to the big tech companies. The overlapping composite of all those photos is what gets uploaded to our phones - and big tech would love for us to assume it’s infallible. I mean, a satellite photo is a photo of what’s actually there. How could it lie?

Try telling that to the crew of the Australian research ship R/V Southern Surveyor, which in November 2012 sailed past the South Pacific island of Sandy Island - first recorded in 1774 by Captain James Cook - and, finding nothing but ocean over a kilometre deep, officially undiscovered it.

They weren’t the first to do so: the French Naval and Oceanographic Service removed the island on its nautical charts in 1974, and in April 2000, a group of amateur radio enthusiasts on a DX-pedition (a radio-mapping journey to a remote place - “DX” is telegraphic shorthand for "distant") found absolutely nothing at its alleged location.

Despite their agitation for an official undiscovery, Google didn’t listen. Their Maps service continued showing a rounded shadow 15 miles long and 3 miles wide as a patch of dry land, and since recorded sightings of the island went back hundreds of years, there should be something there. Surely?

In 2012, a group of scientists set sail to investigate further:

“We all had a good giggle at Google as we sailed through the island, then we started compiling information about the seafloor, which we will send to the relevant authorities so that we can change the world map.”

“Australia's Hydrographic Service, which produces the country's nautical charts, says [Sandy Island’s] appearance on some scientific maps and Google Earth could just be the result of human error, repeated down the years.

A spokesman from the service told Australian newspapers that while some map makers intentionally include phantom streets to prevent copyright infringements, that was was not usually the case with nautical charts because it would reduce confidence in them.

A spokesman for Google said they consult a variety of authoritative sources when making their maps.

"The world is a constantly changing place,” the Google spokesman told AFP, "and keeping on top of these changes is a never-ending endeavour'.”

- BBC News

So there you have it. Google’s official definition of “constantly changing” in this instance means “it’s entirely possible that despite this thing being on all our digital maps, it doesn’t actually exist - and it never did.”

(It’s probably going to get worse in the future. The myth of Sandy Island likely endured because of human error. Imagine what havoc the intentional use of deepfake technology could wreak, as this alarming example shows. Could future authoritarian rulers with full control of insular versions of the internet quite literally wipe their enemies off the map, and claim anything contradicting them is ‘fake news’? Not impossible to imagine.)

Here’s what our map is telling Al and I, as we trudge into the growing darkness.

I’m sure there are plenty of clues here for the mapreading detective: traces of ancient lime burning, with the limestone quarries to the west. Or the moorland to the south, with everything it'll have to say about prehistoric folk chopping down trees. Or the way the paths lie, and what they string together. Or how “Grouse Butts” probably isn’t as demeaning to grouse as it first appears. And so on.

Once we get among the trees, the stillness presses in. What I took to be silence out on the open moorland was clearly a rich, noisy silence with lots of body to it. This? It’s intimate, stifling and deadly. You emit a sound, and a few feet away it drops into the snow and dies. Musicians pay good money to kill sounds like this.

I’d give anything to hear a bird sing.

With darkness racing in, Al and I step up the pace. Ahead, wan light spills down from a ragged opening in the treeline, revealing a steep drop. This is not territory to go stumbling around in at nightfall. But then we find a path, and quickly decide we’re not straying from it. Not once. We will live and die on this path. We will be known as Mike And Al Of This Path.

Now it’s time to search for a nice spot to lay our bivvy bags. Sadly, there isn’t one, so we settle for the least horrible alternative: a small clearing. There’s a metal bench in one corner. I’ve rarely seen anything look more out of place. It’s like finding a parking-meter in the middle of Mordor.

And on top of it:

Um. Stay calm.

Al sets up his tiny wood-burning stove (twig-burning, really), while I go in search of either fuel for the stove or a quick death at the hands of Wildlings, White Walkers or the Blair Witch, whichever comes first.

What I like about small, terrifying adventures like this is they can be had anywhere, even safe-looking places on your maps.

To the inexperienced eye, modern maps are soothing, undramatic and almost maddeningly benign. It’s easy to get complacent if you haven’t learned through joyous or uncomfortable experience what you’re actually looking at.

Contour lines are a common trap for the inexperienced or clueless. I once terrified my friend Charlotte when we were driving from the top of the Moors down into Whitby, by suggesting we turn off down a sideroad that skirted the town centre. On the map I was reading, the route looked uneventful - a single contour line crossing the road, no sweat, even for a wee car like Charlotte’s. Unfortunately I’d missed that it was actually half a dozen lines sandwiched together, which I tried to explain to her as we plunged down a 1 in 3 (33%) gradient on loose gravel, both of us displaying a range of facial expressions you see on viral rollercoaster videos.

(It may just be a coincidence, but I haven’t been asked to do any map-reading for her since.)

But maps don’t tell you what the place will feel like. They don’t tell you the difference between, say, a sunlit clearing raucous with birdsong in an English wood on a baking summer’s day, and that exact same clearing in the dead of winter, your breath freezing into your eyebrows, the cold making your ears sing and your lungs ache, and a silence so profound that you can hear a soft crunch-crunch approaching from a hundred yards away, which is either your friend returning with his own handful of twigs, or, or…oh fuuukay ahh good. Hi Al. Yeah, I’m doing great, man. Fantastic.

What maps don’t tell you is your experience of a place. (And fair enough, because that’s not their job.)

They’ll fool you if you let them, there in your warm living room with the map spread out on the floor, your freshly-made cup of tea going cold because you can’t stop…reading it? Picturing it? Whatever is it you’re doing, anyway. But poring over that same map will feel very different when you’re there, in the place itself. It’s not because the map was wrong. It just wasn’t the full story. Not even close.

In this sense, all maps are lying to us. Digital maps, paper maps, travel blogs, travel writing, Tripadvisor reviews, all of it. They’re all lying if we are daft enough to presume they’re telling the exact truth of what we’ll find there, and turn up expecting to find it, which we never do. We all see and experience the world a bit differently - and remake it, for ourselves and others.

In The Un-Discovered Islands, Malachy Tallack considers the aftermath of Sandy Island’s removal from online maps:

“Zoom in to the right place on Google Earth, between Australia and New Caledonia, and the island’s yellow outline can still be seen: an empty shape on the ocean’s surface. For a time, fantastical photographs appeared inside that shape, added by the programme’s users. Green valleys, harbours, waterfalls, forests, a beach resort, even an atomic explosion: the space that Sandy Island once inhabited was filled with the imaginings of people the world over. The photographs were meant to be funny, of course, but they also express a kind of delight that such a space could still exist in the world.”

It’s happened here, too, in this frozen edge of the North York Moors. When Al and I emerge shivering from our sleeping bags next morning, it’s light enough to examine the bench properly.

Under the line of sacrificial toy victims (there, I said it) is a series of six multicoloured waterproof pages of handwriting, telling a rambling yarn, a children’s story, about where we are.

It ignores what our maps say. According to Ordnance Survey we are in Clain Wood – but this story transforms our surroundings into “echo echo Echo Wood.” (Not so aptly named in all this sound-murdering snow.)

Other places nearby have other unofficial names, all of them sounding like they belong in a Narnia or Harry Potter tale: imaginative, descriptive, somewhat daft, and extremely English.

We have no idea who made this story. We have no idea how to find out - which I guess is exactly what the writer intended. It’s not someone’s attempt to become the next JK Rowling. It’s there as a work of playful creativity: a whimsical reinterpretation of this landscape for anyone passing by. A single story, released into the wild, making a home for itself.

Your map says there’s nothing here? Oh, how little maps know about the world, my friend! Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

Maps are wonderful - especially the fake ones, in my opinion. But they don’t actually take you very far on their own. They should never be treated as anything more than a prompt for your curiosity, the beginnings of a fine (or even ludicrous) excuse to explore somewhere new.

New to you, I mean. Arguably the only definition of “new” that has any tangible meaning to us in the long run. Of course other people have been there and done that, long before you did. That’s always the way: pure originality is as much of a myth as Sandy Island. But you haven’t been, and that always matters. Until you’re on the map too, some mysteries will remain hidden to you. Sometimes you have to turn up in person, scrape off the snow, and see what’s what.

There’s always a new story for you to find out there.

Images: Mike Sowden, Microsoft/Ordnance Survey.