Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a somewhat gormless but enthusiastic romp through the scientific world in search of a good “wow!”

And I guess the sight of 30,000 pigs floating down a river would qualify?

As this writeup from 2011 points out, 30,000 is a truly astonishing number of floating pigs, so the reporter is to be commended for their spectacular lack of curiosity that led to this error making it into print.

Based on a slapdash calculation of the average pig weighing between 140 and 300 kilograms, that is over 6,600 tonnes of buoyant swine - and a lot of displaced river water. Imagine 120 fully loaded M1 Abrams tanks toppling into your local river! Enough to burst the Dawson’s banks? I’m no Randall Munroe, so I invite anyone reading to do the math here and prove me right or wrong. (The river in question is this one.)

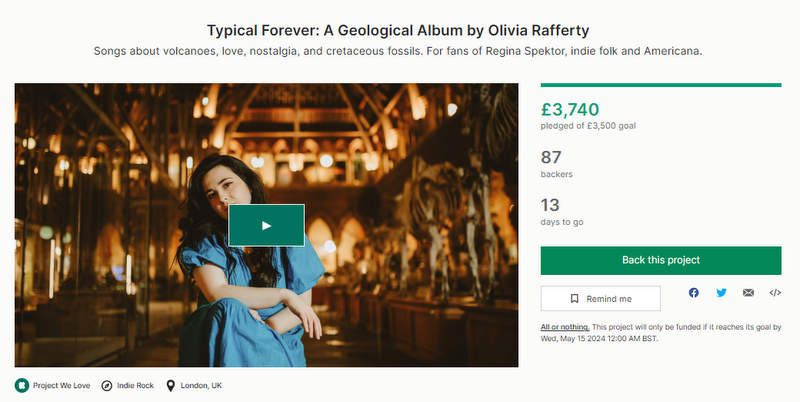

Secondly & infinitely less ridiculously - I love it when science and Art get in the same room together and cause a ruckus, so congratulations are due to Scottish songwriter and Substack newsletter writer Olivia Rafferty, whose debut album of songs inspired by geology is now a successful Kickstarter!

In her own words, it’s “songs about volcanoes, love, nostalgia, and cretaceous fossils. For fans of Regina Spektor, indie folk and Americana” - and it’s supported by no less than the UK’s Geologists Association. Olivia has produced the album herself, and started the Kickstarter campaign to cover an additional radio plugger, CD manufacturing and a filmed live session.

The month-long fundraiser went live on April 15th and hit its first target in 5 days, which says a lot for the love it’s getting. Now Olivia is aiming higher:

Help Olivia launch this thing properly by clicking here!

Okay, to today’s business.

For this audio-narrated edition of EiA, let’s talk about how wrong you can be about something as predictable as a coin toss, and what that can teach us about living a more curious life…

And we start with an American grocer on a double-date with destiny.

Transcript:

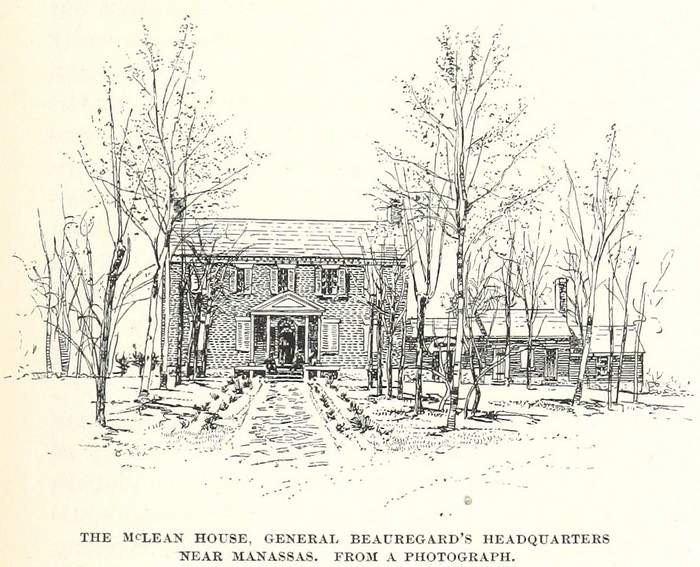

On July 21, 1861, the first major engagement of the American Civil War - now called The First Battle Of Bull Run - took place on the property of Wilmer McLean, a wholesale grocer from Virginia.

McLean's house just north of Manassas had been commandeered by Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard as a headquarters for Confederate forces, and when Union Army artillery opened fire on it and a cannonball dropped through the kitchen fireplace, the idea presented itself to McLean’s mind that perhaps this wasn’t the safest place to raise his family.

In the Spring of 1863, he moved 120 miles south to a house in Appomattox County, Virginia - and on April 9, 1865, his home was once again taken over by the Confederacy to provide the location for General Robert E. Lee’s formal surrender to Lieutenant General Ulysses E. Grant.

It’s apocryphal, but McLean is supposed to have later quipped, “The war began in my front yard and ended on my front parlor.”

*****

What’s your reaction when you hear a coincidence like that?

Does it make you think that the world is deep and strange and filled with hidden undercurrents of meaning that we’ll never fully understand (and maybe you hate the word “coincidence” here because it sounds so mechanical and unromantic)? Or does it make you think that the physical laws of our universe are amazing and science can so easily look like magic?

What I hope you feel, above all, is uncertainty. Something as weird as this should feel like a puzzle that hasn’t been solved, because, well, it hasn’t! It’s bizarre. Nobody knows exactly why the Civil War chased McLean across Virginia in such a purposeful-looking way - if there is a “reason” at all, which there may not be, in the sense we humans tend to clamour for.

(If anyone confidently suggests otherwise, they’re being tiresome and should probably be avoided, especially at parties or at the pub.)

Yes, I write a science newsletter - but this edition is not one that will try to explain away freakish-looking events using science, mysticism, math, religion or anything else. I’m not here to lip-curlingly debunk miracles, or pour scorn on soulless-looking statistics. There’s too much uncertainty here for dogmatic explanations, and that uncertainty contains a lot of the fun. Because, isn’t it fun wondering? Can’t we just sit with the mystery and the questions it raises and the possibilities it opens up, without demanding a final opinion that stops our curiosity in its tracks?

Great! I knew we’d get along.

But let’s face it, you are having a strong instinctive reaction here. You can feel in your gut when something’s so staggeringly unlikely that it can’t just be some random fluke so there must be something more to it. And that feeling is always worth trusting, yes?

Well … no.

Welcome to yet another cognitive glitch in the software running inside our heads - and it’s a weird one, that’s a fact.

*****

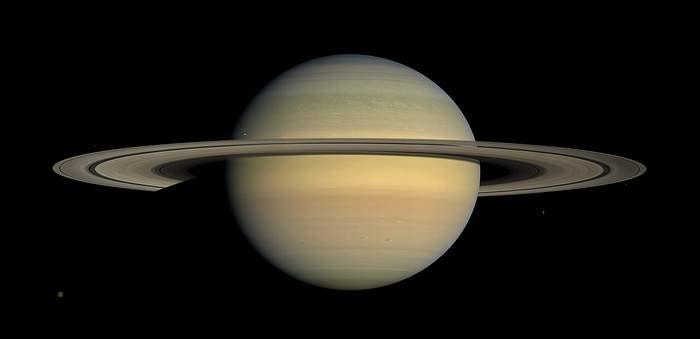

On July 30th 1610, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei pointed his telescope into the sky and became the first person to see the rings of Saturn.

Alas, marvel of engineering for the time that his instrument was, it didn’t show him much more than a couple of fuzzy “ears” on either side of the planet - so Galileo logically concluded that Saturn was accompanied by two smaller planetary bodies.

He excitedly wrote to friends & family, using an anagram to hide this discovery from prying eyes - turning “altissimum planetam tergeminum observavi” - “I have observed the highest planet is threefold” (Saturn being at the time the outermost planet yet discovered) - into the daunting anagram “SMAISMRMILMEPOETALEUMIBUNENUGTTAUIRAS”.

One of the people who received his letter was the German scientist Johannes Kepler, who eagerly set to solving the puzzle. Unfortunately he mangled the solution, concocting the grammatically awkward “salve, umbistineum geminatum Martia proles” (“be greeted, double-knob/twin-companion, children of Mars”). ‘Gadzooks!!!’ thought Kepler in German - ‘this must mean Mars has two moons!’ This confirmed his hypothesis about a natural progression towards order in the Solar System (Earth having one moon and Jupiter apparently having four, as Galileo had suggested from observations earlier in 1610).

As blind luck would have it, this string of mishaps delivered an entirely correct result - Mars does indeed have two moons, Phobos and Deimos - but it would be another 267 years before it was formally confirmed, so Kepler would never know how phenomenally if accidentally right he was.

*****

There’s a famous experiment that shows the difference between our intuitive grasp of random chance and what it actually looks like in the real world, and it goes like this:

You gather together two groups of people, and ask each of them to flip a coin a hundred times. Only thing is, only one group is actually given a coin, and the other group has to imagine doing those coin-tosses in their heads. Both groups record the results: heads, tails, heads, heads, etc.

Once they’ve finished, a trained statistician enters the room, takes a look at each group’s lists of coin-toss results, and quickly tells them which was done with a real coin and which was wholly imaginary.

It’s an impressive trick.

How can the statistician know so quickly?

What gives the game away?

*****

A few years ago, newly engaged Stephen and Helen Lee were flipping through family photos at their engagement part in New York, and this happened:

Stephen: “So my future mother-in-law's flipping through the album and she sees my dad. And so she asks, oh, oh, what was his name? And my mom tells the name. And my future mother-in-law just nods and moves on and keeps on flipping through the book-- doesn't even say anything.”

What Helen’s mother had just seen was the face of the man she nearly married in Korea in the 1960s, before she was warned off by her disapproving parents - and that man was Stephen’s late father.

As Stephen told This American Life:

“To think that I can talk to my mother-in-law and hear what he was like in his 20s-- something that my mom doesn't even know. And my-- actually, Helen's father is a strong believer in the idea that somehow my dad-- somehow is behind all this. That somehow he's helped make all this happen.”

*****

In the words of Professor Katy Milkman, James G. Dinan Professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and host of the superb podcast Choiceology:

“Improbable things happen all the time. That’s how probability works! But humans typically aren’t great at reasoning about probability as they go about their everyday lives.”

In the aforementioned coin-toss experiment (which you can hear enacted in this episode of Choiceology), the difference between the real coin-flip results and the imagined ones was their lumpiness.

If you flip a coin a hundred times in a row, you’re going to have a lot of “unlikely” streaks - say, tails coming up 7 times in a row. But the group that imagined the coin-flips were far less likely to include such streaks, because that kind of pattern flies in the face of what we think of as randomness. It just doesn’t look random!

*****

In June 2001, 10 year old Laura Buxton of Stoke on Trent, England stands in her front yard holding a red balloon, which she’s written “Please return to Laura Buxton” onto, with her full address on the other side. She lets it go, the wind grabs it, and it quickly disappears from sight.

The balloon quickly travels south, across the neighbouring counties of England, until it touches down in the middle of the village of Milton Lilbourne in Wiltshire, 140 miles away, in the yard of…

Another 10 year old Laura Buxton.

Southern Laura followed up with Northern Laura, and eventually they met - when they discovered:

they were both wearing pink sweaters with jeans

they both have a 3 year old black Labrador Retriever

they both have a grey rabbit

they both have guinea pigs, which they both brought with them the day of their meeting - and they looked “identical”.

You can hear the full story at the beginning of this fascinating episode of Radiolab.

*****

We are born to see patterns in everything.

Just ask me in 2019, when I cracked open six double-yolk eggs in a row in an Airbnb in York:

Impossible! Inconceivable! What are the odds! Should I go out and buy a lottery ticket immediately?

(Consult the newspapers and you’ll find odds like one in ten trillion - but since many British supermarkets already sell boxes of guaranteed double-yolk eggs, the possibility of a simple mix-up feels a lot higher. Impossible to know!)

But since our sense of what randomness should looks like is so far removed from its often startling lumpiness in real life, it’s easy to tell when we’re faking it. That’s what that statistician did. He saw a streak of heads or tails that no human would feel comfortable ascribing to pure chance, and he identified reality from imagination.

So what does this say about our intuition - that thing we spend so much of our lives relying on (or cursing ourselves when we fail to do so)?

*****

On August 6th 1945, Japanese engineer Tsutomu Yamaguchi was on a business trip to a nearby city when he heard the sound of a large plane. He watched as it dropped two parachutes - and then the sky split apart and he was flung to the ground. The Hiroshima bomb detonated around 3km away, rupturing Yamaguchi’s eardrums and inflicting serious radiation burns. He crawled to safety, spent the night in an air-raid shelter, and then decided to return home the next day to recover.

At 11:00 AM on 9 August 1945, Yamaguchi was describing the Hiroshima bombing to his supervisor in his workplace in Nagasaki when the second bomb detonated above the city. Yet again, Yamaguchi was 3km from the epicentre, but this time he was largely unhurt by the explosion.

On the 10th January 2010, after an eventful later life as a vocal advocate of nuclear disarmament, Tsutomu Yamaguchi - the only person officially recognized by the Japanese government as a survivor of both bombings - died at the age of 93.

*****

In 1974, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky published this now-famous paper on how unreliable our intuitive grasp of probability can be - and it starts with a lovely metaphor that, as a former travel writer, I couldn’t be more haunted by:

“The subjective assessment of probability resembles the subjective assessment of physical quantities such as distance or size. These judgments are all based on data of limited validity, which are processed according to heuristic rules.

For example, the apparent distance of an object is determined in part by its clarity. The more sharply the object is seen, the closer it appears to be. This rule has some validity, because in any given scene the more distant objects are seen less sharply than nearer objects.

However, the reliance on this rule leads to systematic errors in the estimation of distance. Specifically, distances are often overestimated when visibility is poor because the contours of objects are blurred. On the other hand, distances are often underestimated when visibility is good because the objects are seen sharply.”

You probably know this as the amazement you feel when looking out of a plane window on a crystal-clear day: you know the ground below you is unusually far away, far enough to normally see the hazy “blue of distance” if you were at ground level, but because it’s so clear below you (and yet so far), your brain yells WOW WOW EVERYTHING IS SO TINY THOSE HOUSES ARE LIKE THE ONES IN MONOPOLY HOW CAN THIS BE???

That’s how certain, and yet how utterly wrong, your instincts can be when it comes to weighing up probability.

(Emeritus Princeton psychology professor and Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman passed away on March 27th. Katy Milkman, who is also on Substack, just published a lovely roundup of tributes to him here.)

*****

Sometime in the 1980s, a young boy from Yorkshire takes a trip to Britain’s Scilly Islands, off the west coast of Cornwall.

When the boy (let’s call him AOTN, short for Author Of This Newsletter) sits with his parents in the seats assigned to them, a hand claps down on his shoulder.

“Well, fancy seeing you here!”

Behind them is their local GP from East Yorkshire, who just happens to be on holiday at the same time, travelling the 380 miles to Scilly on the exact same day as AOTN and his parents, and he’s chosen the same sailing of the ship from Penzance and he was randomly assigned the seat directly behind them, from 600 other passengers!

Well, it must be fate.

*****

A few years back, I wrote about the power of pareidolia to make us see faces in the most random of everyday things - and in 2022, I had a whole season on visual illusions that showed how, under unusual conditions, your eyes absolutely cannot be trusted.

The same seems to be true for what we call our ‘gut’. Not always! Our instincts have done a remarkable job at keeping us safe and pointing in a sensible direction for the last 300,000-ish years.

But they can also lead us astray. We see patterns where perhaps (not definitely, but perhaps) there are none - and we can misinterpret the everyday wonders that can happen around us, rejecting raw possibility for reassuringly dogmatic narratives that lead our thinking astray when we neglect to fact-check it properly or refuse to admit we’re unsure.

(Another fun example, again via that Choiceology episode: when the iPod Shuffle was first introduced, its shuffling feature was truly random - but some people complained because they were encountering streaks of songs from the same artist, in exactly the same way as coin-toss streaks. So Apple included a “more random” feature, Smart Shuffle, which you could toggle on and off - which in fact made it less random, by removing its ability to randomly queue up rows of songs by the same artist.)

If we find our gut is ever speaking to us with confident certainty, and we choose to believe that certainty, we’re pulling the plug on our curiosity. Why look for more answers? We already have the right one! What more is there to learn?

Instead, treat it like the unreliable narrator it truly is - especially when it comes to spotting randomness. That at least is something you could put good money on.

*****

“Scientists have calculated that the chances of something so patently absurd actually existing are millions to one.

But magicians have calculated that million-to-one chances crop up nine times out of ten.”

- Terry Pratchett, Mort.

Images: Robert Underwood Johnson & Clarence Clough Buel; Joe Fungelcio; NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute; Riho Kroll.

As a lifelong player of games using dice as random number generators for resolution, I was interested to learn some years ago that if run long enough a series of random numbers is recognizable as not random. However, the real dispute is with my wife who refuses to believe that there is a psychic relationship between the thrower of the dice and the dice which can get quite emotional to the regret of the dice thrower.

I mean what are the odds of my reading this exact newsletter that I subscribed to more than a year ago?!?!?

It must be fate, amirite?

And that was a great episode of Radiolab.