Hello again! After a short pause, welcome to week 5 of Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about applied curiosity - the How of it, the Why of it, and occasionally the WTF of it.

If you’re reading this on the Web and wondering why the hell you ended up here, you can save yourself future self-recrimination by signing up to the email version below:

Okay. Let’s get started.

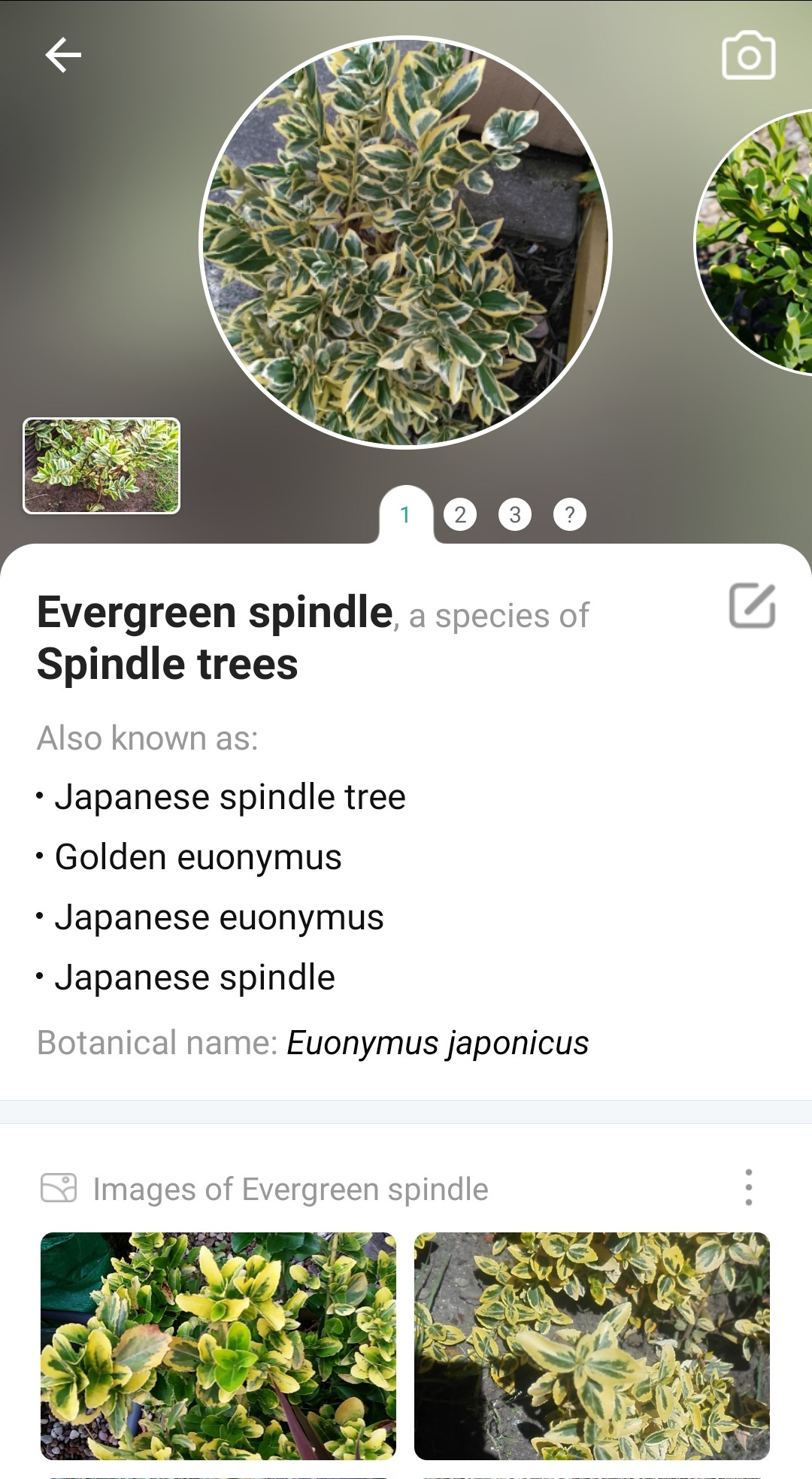

Here’s a Mysterious Living Thing (MLT) growing just outside my current home:

It was planted by my landlords outside the cabin I was occupying last March when the pandemic began, which I’ve now returned to. It wasn’t much to look at back then, but I set myself the task of looking after it, watering it every day, and…er, I didn’t exactly know what else. Did it want sunshine or shade? Did it require exercise?

A lot of the natural world I encounter comes under this personal MLT classification. It’s not something I’m proud of, but it definitely makes things easy for me, and it’s honest about how clueless I am about the natural world, how vanishingly little I know. It’d be nice if I did know, of course. But I usually don’t - and this plant was just another example.

Then I discovered the PictureThis app:

Oh wow. Okay then! My pandemic plant-child was an Evergreen Spindle - or perhaps “japanese spindle tree” (fancy foreign names make everything sound better). What an amazing app. I feel so much smarter.

Except, the next day I’d forgotten the name. Japanese something? I pulled out my phone and used the app again - aha. Yes. That.

The next day, same thing.

And this kept happening. Nothing really stayed in my head - but why did it need to?

If I want to turn flying, feathered MLTs into birds, I could use the amazing Warblr app, or BirdNET. If I want to put a name to insects or animals, I could use iNaturalist. Using them makes me feel like a genius, sending me straight to the answers I need with stunning speed and accuracy. It’s like magic.

And since it’s so damn easy to use these services, and since basically everywhere has phone signal these days, why bother learning names, and the identifying features that lead you to that name? Why devote time and effort to making those things stick in your memory?

What’s the point if there’s always an app that’ll do it for you?

The implications of this are alarming, to say the least. As I’ll be explaining later this week, offloading most of our longterm memory onto the internet isn’t just making us unhealthily dependent on our phones. It’s also short-circuiting our curiosity, leading directly into misery-inducing anhedonia and shoving us down a slippery slope towards a numb, depressed state of disconnection from everything around us.

(I swear I’m not being over-dramatic. More on this in a few days.)

Plus, it’s not always that practical. Yeah, you can merrily app your way around the plants in your garden. But birds are fast. By the time you bring your phone up, they’re gone. The ecologist who took this photo a few days ago got lucky - and the photographer who captured this jawdropping display invested months in bagging it.

There’s a good reason these bird-identifying apps use birdsong. We’re still not quick enough for anything else.

Oh, if only we had something even faster than a camera lens attached to a microchip. Wouldn’t that be fantastic?

Here’s the challenge for myself this week.

Following the classic Animal-Vegetable-Mineral format, I’m going to learn either a species of plant, a species of bird or a type of rock or mineral, one per day in rotation, using the back garden, some nearby woodland and the stretch of beach at the bottom of my street.

I will learn to identify them at a glance - and I will learn at least one of their popular names (nothing more for now, since the Latin stuff can get tricky really fast).

To learn something’s name is a powerful thing. It’s an invented name, of course, a human name. We don’t have anything else right now. (Who knows what names other creatures use for themselves?) In Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard Of Earthsea, learning something’s True Name is to gain total power over it - but also, in her world and ours, naming goes the other way, a little like the Ben Franklin effect. Once you can put a name to a thing, you feel drawn closer to it. Suddenly, out of nowhere, you find you care, in a way you never could when everything was just yet another Mysterious Living Thing...

So that’s my aim here. I’ll report back later.

(What about you? I have fifteen suggestions here, here and here - plus an explanation of why it’s so important to have a go at something, the more random-seeming the better.)

Images: Victor Freitas; Mike Sowden.