The Worst Dam Idea In The World

Lessons from Atlantropa, the megaproject to unite Europe (& erase Africa)

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about science, curiosity and the joy of a good Wow.

Today we’re wrapping up the main theme of this season - the 71% of our planet we’re predisposed to consider much less interesting than the 29% we live on. And we’re coming full circle, returning to the location of the mindbogglingly dramatic ancient flood that filled the dried-out Mediterranean Sea.

Surely only someone with a very tenuous grip on reality would look at any part of this cataclysm and think, “hey, what a great idea! That would solve everything.”

This is his story.

It’s 1928, and German architect Herman Sörgel has had a great idea that would solve everything.

Working as an architect and journalist in 1914, Sörgel was ill-prepared for the horrors of The Great War. His training was in the Bauhaus school of architecture, and his interests were philosophical ideas of culture and space relating to geopolitics. War seemed like a total breakdown of both of these: a devastating force that tore through the world and left nothing standing.

It was enough to turn him into a self-avowed pacifist. But he wanted to go one step further: to not just deny the validity of war, but to engineer it out of existence.

In Sörgel’s view, this was an urgent matter. The future as he saw it would be dominated by three superpowers: one stretching across the Americas, another a Pan-Asian block in the far east - and, most dangerously, a greatly weakened post-war Europe in the middle, currently unable to resist being dominated by the other two.

What was needed was a project so ludicrously ambitious, yet so immeasurably beneficial to all the European powers, that it would at last force them to put aside their differences and cooperate, if they wanted to reap the spectacular rewards on offer.

(And if it was expensive enough - wouldn’t that make it impossible for them to keep throwing all their money into building new armies, navies and air-forces? Wouldn’t it engineer peace?)

This is why Herman Sörgel decided it would be best for everyone if he drained the Mediterranean.

When the 1980 deep-sea thriller Raise The Titanic! bombed at the box office, clawing back just $7 million of its then-astonishing $40 million budget, its producer Lew Grade quipped “it would have been cheaper to lower the Atlantic.”

Okay, I laughed too. But - purely as an exercise in trying to answer hilariously daft questions - how much would it cost to lower the level of the sea? (And considering sea levels are set to rise over the next century - is there anything that can be done to reverse it?)

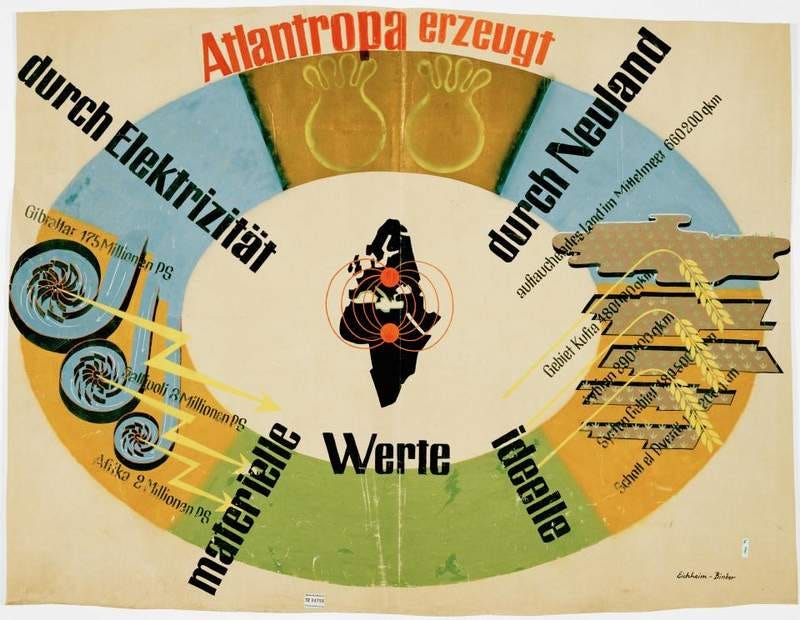

Sörgel’s answer was to let Nature do it for him. His project would take hundreds of years to complete (thereby hopefully shepherding humanity into a gentler, more rational age and away from all this Blood & Iron nonsense). Even better, it would pay for itself, giving every investor - namely, the wealthier countries of Europe - a huge financial return over time, mainly in the form of a near-unlimited source of electrical power…

And it would create new land for Europeans to settle on - both within the Mediterranean, on reclaimed coastline totalling 660,000 km² (by comparison, Spain is around 500,000 km²), and across huge tracts of land in the unpopulated continent of Africa.

(Yes, yes, I know. “Unpopulated.” We’re…going to get to that.)

Here’s how it would work.

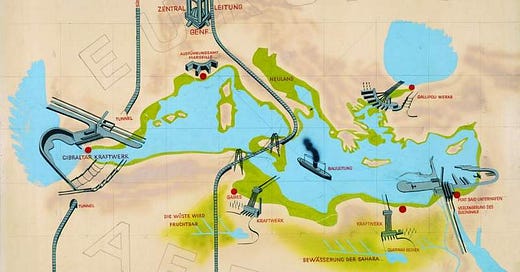

(Exhibition poster from 1932, via Environment & Society Portal.)

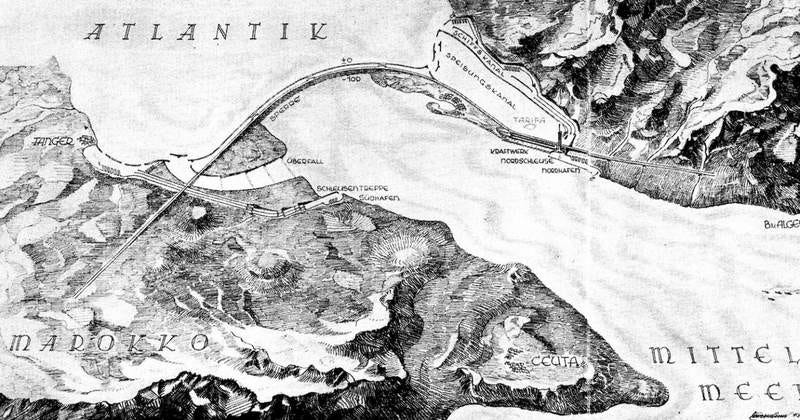

First and foremost, a hydroelectric dam would be built across the Strait of Gibraltar, preventing the Atlantic from replenishing the almost entirely land-locked Mediterranean, and providing Europe (the richer parts of it anyway) with most of its electricity.

This would trigger a human-engineered repeat of the Messinian Salinity Crisis, the geological event that led to the almost complete dessication of the Mediterranean - and ended with the jawdroppingly violent Zanclean Megaflood.

After a couple of hundred years of drying-out, the sea on the Mediterranean side of the Gibraltar dam would be around 100 metres lower than on the Atlantic side, creating a vast, renewable source of potential energy that could be turbined into electricity.

Since all this clearly wasn’t ambitious enough for Sörgel, the next step would be building four other dams:

Across the Dardanelles to hold back the Black Sea

Between Sicily and Tunisia (also providing a handy roadway from Europe to Africa), allowing the deeper-floored eastern Mediterranean to be lowered an additional 100 metres

At an extension to the Suez Canal, creating sea-lock access to the Red Sea

On the Congo River, below its Kwah River tributary, to refill the vast basin of land around Lake Chad, thus creating enough fresh water to irrigate the Sahara (!) and lay down a shipping lane into the African interior.

The combined result of this would be known as Atlantropa - a theoretically peaceful, technology-led way to meet Europe’s needs, allow Europeans to expand into Africa, and forge a united front against the threat of the Americans in the west and Asia to the east.

It’s hard to know where to even start with all this - so let's head to the Strait of Gibraltar, the place where, just over 5 million years ago, the Atlantic was pumping around a hundred million cubic metres of water a second into the Mediterranean.

If you check that exhibition poster again, you’ll see the red dot marking the proposed Gibraltar dam seems a little to the right of the narrowest point of the Strait (where it’s 9 miles / 14 km of sea between Spain and Morocco). This isn’t a mistake: for engineering reasons that appear to be lost to us, Sörgel decided the dam should be built 30 km further inside the Mediterranean - meaning it would have to be even longer than the Strait itself.

Once its foundations were built (2.5km wide, 300m deep) and once its entire length was laid out across the seaway, a 400-metre-high tower would be erected - all of this requiring … um, more concrete than existed in the world at that time, it seems.

The dam wall would have to be high enough to prevent Atlantic gales from pounding water over the top, and deep enough to reach to the seabed (anything from 300 to 900 metres deep, depending on the location). And it would have to stretch for at least 25 kilometres, probably more.

By contrast, the largest hydroelectric dam in the world today, the Three Gorges Dam in China, is 2.3km long, 185 metres from base to top, and took 17 years to build with modern construction technology. Atlantropa’s Gibraltar dam would be on another scale entirely.

It wouldn’t just be a mammoth undertaking: it would require a collective engineering effort never before seen in human history.

(And it’d still only be the first dam of five.)

Science fiction writers have a lot of fun with disasters. In Red Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson imagines what would happen if a space elevator (a cable connecting the surface of a planet to low orbit, allowing goods to be mechanically hauled up it without burning fuel to escape the planet’s gravity well) was violently untethered by terrorists. Answer: it’d fall back down, wrapping itself 2.5 times around the planet as it did so with increasing fury.

And in Julian May’s Saga Of The Exiles, the Zanclean Megaflood is the work of a time-travelling freedom fighter (or terrorist, if you’re one of the aliens occupying Earth at this time), who plants a bomb in just the right place to breach the Gibraltar land-bridge and wash away the invaders.

All big engineering projects should hire scifi writers and ask them what could go wrong. Atlantropa is no different. What would happen if someone who perhaps didn’t like the idea of a Europe controlled by a Third Reich went and planted a bomb to really hammer this home, triggering a new Zanclean flood and a colossally scaled-up version of the finale of Force 10 From Navarone? What if that happened when all those newly-reclaimed lowlands had been populated?

Yeah. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

But this is far from the worst thing about Atlantropa.

When the Nazi Party came to power in Germany, Sörgel took his plan to Hitler - who proved sufficiently enthusiastic about the idea that Sörgel's 1938 book Die Drei Grossen A: Amerika, Atlantropa, Asien has an endorsement from him on its cover.

Sörgel saw Atlantropa as a way to remove the need for geopolitical conflict, and described himself as a pacifist. But beyond his romanticism and idealism, he clearly held a number of fairly commonplace views that would be abhorrent today.

For example, he referred to Europe as “people without space,” while Africa was “space without people.” Along this line of thinking, Africa was a vast, unspoilt playground for the major European powers - and Atlantropa would be the triumphant finale of the 19th-Century ‘Scramble for Africa’ that inflicted all manner of horrors upon the people already living there.

It would be the Nazi idea of Lebensraum (“living space”) brought to terrible fruition.

It’s alarming to look back just a century and realise just how deeply baked and widely-disseminated these kinds of racist assumptions were in Europe. After all, this is four full centuries after the Valladolid Debate argued that the rights of indigenous people were basically either “well, they’re not people, so the argument is meaningless” or “well, I agree they’re not people, but they could be, if they were brought to the glory of God.”

But here was Atlantropa, arguing that Africa wasn’t even worth keeping as a name, let alone anything or anyone currently within it (barring European colonial territory, of course).

Perhaps none of this would have directly occured to Sörgel. Perhaps he’d have been shocked to find himself the tool of a colonial policy of genocide (which is exactly what would have happened). Such is the way of many stories in history and in fiction.

But considering that the population of the Chad Basin today is 30 million souls, and how the creation of a dam there would at the very least have created one of the biggest refugee crises in world history, and considering that this doesn’t seem to have occurred to Sörgel, at least as far as my reading suggests?

It’s proper shivers-down-the-spine stuff.

However, maybe he was onto something else here.

The sheer scale of Atlantropa proved very popular with the public imagination. In 1932 in Germany alone, Atlantropa was featured in over a hundred newspaper articles - and after long after Nazi interest in it waned (too much cooperation, not quite enough brutality), its popularity quietly endured, powered by Sörgel’s tireless support - until 1952, when he was killed while cycling to an Atlantropa lecture at a university in Munich. (This allegedly happened on a road "as straight as a die" and the driver of the car was never found. Make of that as you will.)

Atlantropa may have been wildly unfeasible for countless reasons, a perfect turducken of Nopes. (For example: hey, what would an emptying of the Mediterranean do to the world climate - and the other oceans, which is exactly where all that water would go?)

But the way that so-called “megaprojects” like this have a habit of capturing our attention and stirring us with big, grand What-Ifs - perhaps in a way that ‘every little helps’ messaging fails to do - could the challenges of the 21st Century do with a bit of Atlantropa-style storytelling behind them?

I’ll leave the last word here to Cal Flyn, author of the fantastic Islands Of Abandonment, who recently wrote for Prospect Magazine about the need for big, stirring narratives of hope to turn our problems into solutions:

“A quotation, commonly attributed to the writer and pioneering French aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, says: “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” This, if I ever read one, is a manifesto for nature writing in the present day. This is our own task: to evoke the experience of being in this wild and beautiful world. To stir people to love the planet with a jealous passion, to act in a way more befitting of a custodian or even lover. Go in through the heart, and the head will follow.

We need to be roused. We need to feel. We need a siren song that lures unsuspecting souls to the cause: a song to enchant us, to put us to work.”

If “longing for the sea” is such a big part of it, maybe we’d also get usefully, constructively excited about how fantastic our ship would look like when it’s built?

Season 4 is a wrap! Here’s what we’ve covered - and what’s coming next.

Images: ittiz/Wikimedia; Environment & Society Portal.

Fascinating and terrifying. But it does make one wonder how to harness the oceans for power - without destroying them. We humans never seem to think of the others. Not just the humans but all the creatures that live in the land he would flood?

So very much to unpack in this story. This expression is a priceless gift: "a perfect turducken of Nopes".