Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity, wonder and weird lights in the sky that aren’t actually there (sorry).

This week I’ve mostly been laughing at my friend Geraldine: firstly, at her incredible, stomach-churning restaurant review…

…and then at how it became international news (literally, it was in UK newspapers a few days later) - and then this happened:

It was such a joy to see. It might enjoy it too. Go read her post to find out.

So, to today’s topic, which I’m not looking forward to exploring at all.

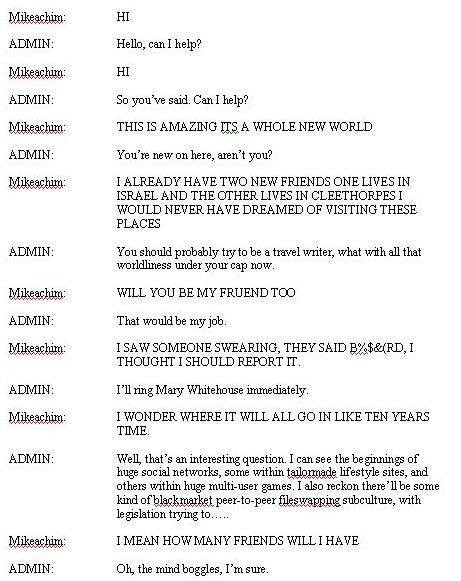

I first joined the Internet in 1998, and one of the first things I did was strike up a conversation with someone doing admin at (I think) AOL Online. It went something like the above. The Internet was amazing! I was excited, curious and hopeful. I couldn’t wait to see what happened next.

Unfortunately, it’s possible that what happened next was - I joined the wrong side.

That’s our topic for today.

Have you heard the shortest published story in the world? It goes like this:

“The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door.”

It’s part of a longer story by American scifi author Frederic Brown, called “Knock,” published in 1948. The longer version is…um, very 1940s? (It features aliens with names beginning with “Z”, so - yeah.)

But what really became famous was that opener, a yarn in itself that’s been quietly tormenting people for over half a century. It’s a self-contained story that could go in a hundred directions:

There’s a supernatural entity at the door.

There’s a zombie at the door.

There’s an alien at the door.

There’s a woman at the door.

There’s a child at the door.

There’s no knock, and/or no door.

He only thinks he’s the last man on Earth.

He’s not a man.

“Earth” in this context doesn’t mean our planet - or some similar nitpicky twist with any of the other nouns in this sentence.

The narrator is unreliable so you can’t trust anything here.

It’s a tree branch tapping against the door, blown by the wind…

I can think of a handful of popular novels that fit each of these scenarios: for example, Nevil Shute’s utterly devastating 1957 novel On The Beach - and if you’ve read it, you know which one I’m referring to.

But the two-sentence story itself gives you nothing. It just ends, leaving you frustrated and annoyed and ready to argue over what it really means with a bunch of similarly exasperated friends or complete strangers.

Really? Was that it? There must be more. What clues did we miss? No, you’re wrong, he wouldn’t do that. Look, I just know, okay?

This is the essence of effective dramatic tension: stringing your audiences along until the next big reveal, always keeping something back from them, and leaving them to marinade in their own frustration.

"Always make the audience suffer as much as possible." - Alfred Hitchcock

It’s immensely annoying, yet it extracts billions of dollars from us every year. (Just ask Marvel.) There’s no question it’s hugely important to professional storytellers, marketers and anyone with anything to sell…

But is it actually good for us?

This may seem like a stupid question to you - but it’s terrifying to me. For the last ten years, I’ve made something of a living by hooking folk with stories, by maddening them in the service of readability, and by being an enormous shameless tease. Even worse, I’ve taught this stuff to other people, in lectures and through a storytelling course. I’m in this up to my neck.

Oh, and since dramatic tension is a way of inspiring curiosity, I’m also in danger of sinking all the arguments for the existence of this newsletter as well. Hooray!

With my heart in my mouth, I went looking for answers.

(Look! I’m still doing it. I’ve already done the research for this newsletter. I could sum up right now what I found. But you’ll just have to keep reading. That’s how awful I can’t stop being.)

Okay. Here’s what I found.

Brace yourself. It’s not all good news.

1. Everything Must Go

Let’s say this Last Man On Earth microstory has been quietly bugging you for a full week now. (If this seems ridiculous to you, translate it into that special thing you care about to a degree that other people might consider equally ridiculous.)

Now you’re out shopping, strolling down the high street. Your attention is grabbed by the word “SALE” in a clothes shop window, so you go in and have a look around. A truly fabulous jacket catches your eye. It’s 60% off normal price - but that remaining 40% is still uncomfortably outside your budget for impulse purchases. If you buy it, you’ll end up more financially anxious for the rest of the month than you really need to be.

But - it’s on sale. You might never get this chance again.

What do you do?

Incredibly, that tiny story-induced irritation in the back of your mind could have a wildly disproportionate effect here. That’s what the work of Kyra Wiggin, Martin Reimann and Shailendra Jain suggests, anyway: in their studies, participants with unsatisfied cravings for knowledge (intensified by the researchers) were more prone to splurging money on a whim than those without an aggravated curious itch.

Why is this?

It seems it’s down to our neurological reward systems, aka. that reckless flood of “oh **** it, my life is hard, I DESERVE this today” feelings that trigger an impulsive purchase:

Curiosity triggers abound in our everyday lives—we often have to wait to read a text message, finish a mystery novel or solve a puzzle. In addition, savvy businesses intentionally build some mystery in their marketing. Companies such as Groupon, JetBlue Airways and Banana Republic offer “secret” promotional deals and mystery products, and other stores distribute coupons but only reveal the amount of the discount at the time of purchase.

The findings by Wiggin and her colleagues might encourage businesses to take the practice one step further—for example, by adding some fun trivia at the entrance to a store, with answers provided on your receipt as you leave. Whether we enter a store in a state of curiosity or our curiosity is piqued by marketing ploys, the result may be the same: we will be tempted to select more lavish items.

- “How Curiosity Makes You Crave,” Cindi May, Scientific American.

So, wow. That’s not good. Us storytellers leaving you hanging - we’re making you buy loads of crap you don’t need?

And considering how deeply these narrative open-loops are baked into…well, everything in modern society (especially marketing of all kinds), is it any wonder we’re under such huge pressure to dull that pain and blow our budgets with impulse-buying?

Thankfully, there’s a way to protect yourself against the financial ravages of dramatic tension. You just need to be a bit more kind to yourself - strategically and preventatively.

It’s counterproductive and anxiety-inducing if you try to bully yourself into ‘responsible’ behaviour. The way to do it is to acknowledge that yes, as absurd as it might seem to the stern, joyless adult within you, you’re jusifiably annoyed that episode 6 of Hawkeye isn’t here yet, or it’s understandable that you’re peeved that you have to wait two whole weeks for the big end-of-season game - and you need to make yourself feel better somehow before you go make any decisions involving money.

In other words: you need to respect the curiosity-driven, story-loving person within you, instead of pretending you’re a totally rational, emotionally controlled Grown-Up (whatever the hell that is, because I’ve never met one).

As I understand this, it shifts the blame a bit. Yes, simmering dramatic tension can seriously mess up all other aspects of your life - but then, so can any other emotional response. But this doesn’t make all our emotions “bad”. It’s how we use those emotions - and how other people use ours - that are the issue here. It’s as much about intent as it is about effect.

But it certainly is also about effect. This is why we need to understand it better. We story-peddlers and curiosity-catalysts can’t just say “oh, it’s not my fault you just spent £37,000 on lunch at that idiot’s restaurant.” Maybe it’s not our fault legally, but we can certainly learn and talk more about the mechanisms affecting everyone’s decision-making abilities due to our sneaky, under-the-radar influence.

So. These findings aren’t great. I feel somewhat queasy. But this is about how we intentionally use curiosity - because of course it can be, and is, misused.

(This is undeniable. Just look at clickbait.)

2. Eee, Them Were’t Days

(With infinite apologies to anyone who has ever played any of the Four Yorkshiremen.)

- I tell you, back in those days, we didn’t know things. Not a thing!

- Aye! Nowt.

- And when you discovered something you didn’t know - which happened all the time - you just had to carry it around with you, or go to a library to fix it.

- Libraries? You were lucky. Where I grew up we only ‘ad one book for the whole village. Five Go On A Hike, by Enid Blyton. If it didn’t contain that thing you wanted to know, you were stuffed.

- A whole book? Oh, we used to dreeeeeeam of ‘avin’ a whole book. All we ‘ad were a page from a newspaper from 1906. AND it were on fire.

- At least you were warm then.

- But they were better times, though.

- AYE.

- Aye. Do you remember the ideas we used to ‘ave?

- Of course! When you spent the whole week fed up because you didn’t yet know something, eeee, it were marvellous what explanations you came up with!

- Marvellous!

- Aye. I read about all this in’t’newspaper. It’s like the opposite of perceptual narrowing - the process whereby infants “unlearn” all the ways to experience the world as they grow up, because of all the societal pressures to behave in more restrictive, more socially acceptable ways. For example, that way babies taste random things to see what they’re made of.

- Right. And when you ‘ad a question that were bugging you all week, you’d keep attacking it in your head from all sorts of different directions.

- “Widening your perceptual scope,” they call it. Like stepping back, so you can bring in more and more of the big picture. More tools with which to treat the problem, allowing you to become more and more creative…

- No wonder most fan theories are better than actual plot twists. All that time spent stewing!

- Oooh, you could end up with dozens of ways to answer stuff.

- ‘Undreds of ways.

- THOUSANDS. I actually invented nuclear fission just because I lost a strap on my duffle-coat and couldn’t work out how to button it without the wind getting in.

- I invented cognitive behavioural therapy because we ran out of teabags.

- I transcended and became pure energy because I lost my car keys!

- Not like today, though.

- No, not like today. Now folk just type their questions into Google an’ they get an answer immediately.

- One answer!

- Aye. What’s the use of one answer, I ask you? But that’s all you get. Type it in, click the first search result, off you pop. No need to even think at all!

- I worry about young people nowadays.

- Aye. Anyway, Clarence, Fred, I must dash, I’ve got a Flat Earth meeting in an hour, don’t want to be late.

- Flat Earth? Do you…do you believe that stuff?

- Of course! It’s on t’Internet. They would have taken it off if it weren’t true.

- Fair point well made.

- Aye.

3. The Other Questions

Let’s say that two-sentence ultrashort story has been gnawing at you for a full month now, and now you hate it. You hate it, you hate authors, you hate stories, you hate everyone, and above all you hate not knowing what’s next.

So naturally you start to rebel against the question itself.

While you’ve been reading this article, a very small part of your subconscious has been returning again and again to that microstory, looking for a new way to frame it so it gives you a truly satisfying answer, a new way to pry it open...

At least, it would be doing, if I hadn’t already listed a bunch of those answers directly underneath.

Those are acting on your brain like the first page of results in a Google search, and they’re now making it very hard for you to come up with anything else. Why bother, quite frankly? One of those eleven answers is probably good enough. Are we done? What a rubbish newsletter this is turning out to be. Ain’t nobody got the time.

Desperate for closure and relief from this irksome, boring annoyance, you deem this answer Good Enough I Guess, and move onwards without a backward glance.

Congratulations! You just successfully turned a mystery - a thing with infinite capacity to annoy you - into a puzzle, a thing you can quickly dispose of, allowing you to seek out new puzzles to process and discard equally quickly.

In a way, this is what Google Search is for. It’s there to take the big unanswerable questions in life (“what is love?”, “what’s the meaning of life?” or “why did they have to resurrect Sex And The City?”) and turn them into hard, fast answers (“a biological trick to perpetuate our species,” “money,” or “money.”)

Why do this? Well - because it saves us time! It means that we can ask more questions in the same amount of time, getting more done and thereby living richer, fuller lives. Obviously!

Google certainly agrees. In 2012, the Guardian interviewed Google’s Head of Search, Amit Singhal, who said this:

"The end game of this is we want to make it as natural as possible a thought process," he says. "We are maniacally focusing on the user to reduce every possible friction point between them, their thoughts and the information they want to find."

But as Ian Leslie notes in his book Curious, our curiosity - and our creativity, period - relies on that “friction”. It’s wholly dependent on us not getting answers immediately, so we can consider the questions long enough for deeper and deeper insights to develop, and continually refine how we phrase those questions, so they get better & better.

The smoking gun here is what Google Search is doing to the quality of our search inquiries. Returning to the Guardian interview:

I imagine, I say, that along the way he has been assisted in this work by the human component. Presumably we have got more precise in our search terms the more we have used Google?

He sighs, somewhat wearily. "Actually," he says, "it works the other way. The more accurate the machine gets, the lazier the questions become. So actually our lives get harder." He had to work especially hard to correct and understand spelling errors and analyse synonyms. And all along the dream has been the old Star Trek one of providing the right answer to what you think you want to know even if you don't know quite how to phrase the question."

But if we don’t know how to phrase the question in the first place, let alone rephrase it - are we even thinking about it?

Good question! I don’t know, I’m too busy writing this newsletter right now, sorry kthxbai.

(However, it’s worth remembering that our skill at asking questions is deeply tied up with social class, as I wrote about here: it’s the middle and upper class families, with a relative luxury of time and money at hand, that raise children with enough privilege to learn how to ask the best questions. This is not a level playing-field, even without Google Search getting involved.)

What we all need is better questions - including ones so rich in possibility that they’re essentially unanswerable. Or putting it another way: we need more mysteries, which are best tackled with the rigor and heart of epistemic and empathic curiosity.

We need to treat questions the same way professional musicians answer queries like “how do you play the piano?” Answer: a lifetime of compounded learning, and of rephrasing the same question again and again in new and exciting ways:

How do you play Chopsticks?

How do you play Beethoven’s Fur Elise?

How did John Lennon play his Steinway Model Z?

How can I play the slow bit of Toss A Coin To Your Witcher?

How can I play Stravinsky’s Trois Mouvements De Petrouchka in front of these 600 people without going completely to pieces?

How do I discover the first theme that will unlock the right flow of emotion so I can go on to score this soundtrack for that upcoming Christopher Nolan film?

(That last achievement might only be available to Hans Zimmer. Although maybe not! No harm in aiming high.)

The role of Art here is to pose mysteries (“what is love?”) again and again, and to refuse to come down hard with a definitive answer, even at the conclusion of that piece of artwork. The result?

We think about these questions properly.

We think about them all our lives.

And perhaps, along the way, we stumble across some answer to them that’s genuinely wise, and actually worth knowing.

(This is also the role of scientists, even though it’s often claimed they’re working in the opposite direction, towards boring certainty. Not so! The more science uncovers about reality, the deeper the mysteries seem to run and the more questions open up. Don’t get me started. Seriously.)

So it seems there’s hope for me and my frustration-peddling peers.

Yes, dramatic tension and questions annoying dangled in the air are incredibly maddening, and can trigger exactly the wrong kind of “dull the pain” commercial behaviour - but that feeling of annoyance, that “friction”, can also be the source of an infinity of meaningful, life-improving inquiry.

In a sense, it’s the essence of “Type 2 Questions” - borrowing from "Type 2 fun,” the kind you have when it’s unending misery at the time (say, climbing a mountain) but then you look back later and realise that pitting yourself against that challenge was the best thing you could ever have done with your day.

Answering a Type 2 Question is the work of a lifetime. Many lifetimes. It’s the work of the human condition, for everyone. And there will never be an end to the curiosity you can invest in these kinds of bottomless mysteries - or the satisfaction and sense of fulfilment they will give you, revelation after revelation.

Tantalizing mysteries can make life worth living - and so can curiosity, as long as it’s the right kind, applied in the right way for the right reasons.

Yeah. Reckon I might be in the clear here. Back to work, I guess?

Images: Markus Spiske / CouponSnake.com; Ana Municio; Reuben Juarez.

When I first saw the foaming chef’s mouth vessel on Twitter I glanced at it thinking is was a parody. And then I kept seeing it and read further. 😂

This was such an excellent and thought-provoking piece all around. Thanks!