Hello! Welcome to Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about the joy of searching for what you never knew you didn’t know.

As promised in the last rainy edition, I’ll be in your Inboxes later this week with season 6’s first piece about the science of islands - but first, an unscheduled interruption.

With all the crappy stuff going on in the world, we now have the new owner of Twitter using it to trash Wikipedia:

(Note the way that even Twitter’s community fact-checkers are calling him out on it.)

EDIT: As Gary notes in the comments, Musk’s question aimed at Wikimedia could be seen as a simple innocent factfinding query along these lines - except for all the other childish nonsense he’s slung at Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, including calling it “Wokipedia,” and the ongoing battle over the Wikipedia page profiling Musk. In short: it certainly looks personal?

I love Wikipedia with all my heart.

(And I’m far from alone. Here’s Brendan Leonard on why the Wikipedia app has made his life better.)

Yes, it's a bit unreliable, and it's very occasionally spectacularly inaccurate (more on that below), but generally speaking it's that rarest of things, alongside sites like Aeon and this guy’s webspace: something on the Internet that's genuinely constructive, inspiring and useful.

So, if you’ll forgive me, here's a repost of a newsletter from the second season of Everything is Amazing, all the way back in 2021. It’s an enthusiastic appreciation of my favourite thing about Wikipedia: how even its flaws are something to admire.

It’s December 2012, and someone’s just noticed something is wrong on the Internet.

Wikipedia editor ShelfSkewed (happily that’s a pseudonym) has been clicking links in an article about an obscure 17th-Century war that raged between the Portuguese rulers of Goa, western India, and the neighbouring Maratha Empire. It was called the Bicholim Conflict, after the North Goa district it mostly took place in.

Haven’t you heard of the Bicholim Conflict? ShelfSkewed certainly hadn’t. He wanted to know more - and started investigating the extensive sources listed at the bottom of the article.

But then he found many of the links led him straight to one article: the one he was editing. A perfect loop.

Ruh-roh.

A few days later, he was ready to report in:

“After careful consideration and some research, I have come to the conclusion that this article is a hoax—a clever and elaborate hoax, but a hoax nonetheless. An online search for "Bicholim conflict" or for many of the article's purported sources produces only results that can be traced back to the article itself. Take, for example, one of the article's major sources: Thompson, Mark, Mistrust between states, Oxford University Press, London 1996. No record at WorldCat. No mention at the OUP site. No used listings at Alibris or ABE. I can find no evidence anywhere that this book exists. Not being able to find any trace of an OUP book published within, say, the past 40 years? Ridiculous. If this book exists, then the original author of this WP article owns the only copy.”

A prank, then. An absurdly elaborate one, since this 4,500-word (!) article was absolutely convincing at first glance. The work of a master-forger.

And for that reason, nobody had spotted it for five years.

If you’re a freelance writer or a college student, feel free to break out in a sweat here. How many times, when deadlines are threatening your sanity, have you failed to heed the excellent advice that Wikipedia should only be used as the starting-point for your research? (Yep. It me.)

Other Wikipedians weighed in:

“The editor who created the article has not done a lot of editing outside of that article and has not edited since 2007.”

The likely suspect, pseudonymed A-b-a-a-a-a-a-a-b-a, had the additional cheek to nominate the article for the highly prestigious “Featured” status. It didn’t get it, because of an “overreliance on weak sources” (but was still convincing enough to fool the site’s editors).

Yet it still managed to get tagged as “Good,” an honour bestowed on just 1% of all the pages on Wikipedia.

The whole thing is ludicrous - and far from unusual.

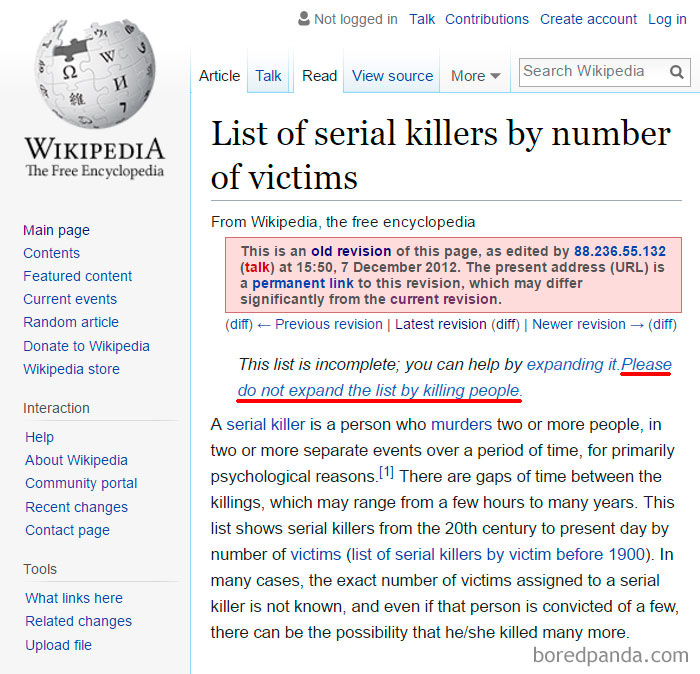

You’re probably aware of the modern phenomenon of the Funny Wikipedia Edit, which Wikipedia itself defines as “Vandalism” even if the intention is mischief rather than malevolence.

Take this addition, now corrected:

As you might imagine, many unverified edits are political in nature…

…or take amiable pot-shots at celebrities:

Some air personal grievances about recent events:

Some have…other axes to grind:

And some are straightforward cries for help:

If you like your humour metatextual, check out the running battles over Wikipedia canon, known as edit wars. If that’s your thing, go here:

“This page documents our lamest examples. It isn't comprehensive or authoritative, but it serves as a showcase of situations where people lose sight of the big picture and obsessively expend huge amounts of energy fighting over something that, in the end, isn't really so important.”

But alongside the funnies (& the far-less-funnies) are the spoofs and hoaxes that were good enough to go undetected.

Compared to the 6 million articles on Wikipedia, they’re the tiniest percentage - but it’s still an alarmingly big list. The 65 that managed to escape detection for more than ten years (!) include a fictitious British slapstick TV gameshow, a fake sheik, a spurious variety of Norwegian associated football, a bogus medieval torture device, an imaginary HBO miniseries (“Sheer Perfection”), a non-existent French actor & opera singer - and an American punk rock band that was as real as Spinal Tap.

How many others have slipped through the net?

This isn’t saying Wikipedia is untrustworthy, though. I recently started reading the digital archives of National Geographic Magazine from 1910 onwards (yet more evidence of how fun I am at parties), and what most struck me were the encyclopedia adverts:

The Wikipedia of its day? Not really, since beyond the obvious fact that once it was published no further edits were possible (unless you buy next year’s updated set, go’orn mate, you know you want to, discounted if you preorder, what say you sir, eh?), it was also the work of a highly…undiverse editorial team. No doubt rigorous within their own fact-checking bounds, but constrained by a single worldview: white, Western, upper-middle-class, wealthy enough to fork out cash for a set of encyclopedias, and so on.

And for you younglings with your long hair & flared trousers (or whatever you folk wear nowadays), here’s what my generation was reading before the internet:

Ahh, Encarta 1994 Edition, you beauty. (I particularly loved the map-like “trees” of articles that you could pick your way through, which felt like a free education from the University Of Life. At one point, I set myself the challenge of reading all 50,000 articles! Yeah. Again with the parties thing.)

But Encarta was yet another “encyclopedia,” in the old style. A small group of people decided what went in and what was left out - and then the results were frozen in time, at the point the software was burned onto CD-ROM.

(Later internet-era editions of Encarta also allowed for downloadable updates of new articles - an early form of software patching, for those willing to fork out for the required subscription package).

In comparison, Wikipedia’s vast, messy fluidity and all those raging arguments between editors (two hundred thousand of them!) feel pretty reassuring to me. I reckon that’s a lot closer to what landscapes of public learning should look like.

In summary: the architecture of human knowledge may look rather more chaotic these days - less reassuringly certain & self-assured, and seemingly prone to more epistemological glitches. But I reckon that’s a good thing. It was always this biased, and always this unreliable. It’s just that we’re seeing it now - and we’re seeing what’s being done about it.

(Sorry, Encarta. I still think you’re brilliant.)

If you find this whole topic existentially upsetting, hey, please read this Wikipedia article about the reliability of Wikipedia!

No…don’t think too hard about that. Don’t. It’s just an internet thing.

Thanks!

Images: Wikimedia Commons; Mashable; BoredPanda; toxi85 at Pixabay; Sam 🐷 on Unsplash

I fucking love Wikipedia. That’s all I have to add. Thank you.

"It was always this biased, and always this unreliable. It’s just that we’re seeing it now - and we’re seeing what’s being done about it." This is so, so true.

Learning how to read and understand Wikipedia with its flaws in mind builds a ton of media literacy. You need that same literacy to read and understand the old Encyclopedia Britannica, only most people didn't realize that because it didn't broadcast and catalog its flaws in the way that Wikipedia always has. Things have actually improved, and part of the reason for that improvement is... Wikipedia is more honest about its mistakes.

It's one of the two greatest websites (the other is archive.org), and it doesn't seem like that's going to change any time soon. It hasn't changed in more than a decade! Thanks for the great piece, Mike.