Fooling With Certainty: The Impossibly Real Worlds Of MC Escher

“Are you really sure that a floor can't also be a ceiling?”

Hello! This is Everything Is Amazing, a newsletter about curiosity.

Thanks to some new subscriptions after one of my Twitter threads went modestly bananas, some of you are reading for the first time. (Hi! Welcome to the really longwinded version with less pictures. I hope that makes you feel hugely excited.)

Before we begin today’s leap into whatever-the-hell-is-this, here’s something I saw a few days ago, and I cannot for the life of me think of a way to naturally fit it into anything I’m writing, so I’ll just drop it here and pretend there’s a reason:

Okay.

In keeping with this season’s theme of optical illusions, floating cities and other brain-bending tomfoolery - let’s look at the impossible work of a man who knew how to look harder than anyone else.

It’s 1938, and Dutch artist Maurits Cornelis Escher is hating the view.

He’s living in Belgium, his latest attempt at making a new home after leaving Italy in disgust at the rise of Mussolini’s fascism. Switzerland was his first port of call, but he found it cold and uninspiring. Nothing to spark the internal fires of obsessive enthusiasm that his work depends on.

Now it’s Belgium, which he’s rapidly growing bored with. In three years, with the War tearing Europe apart, he’ll retreat with his family to the Netherlands, where he’ll stay for the rest of his life. But for now: sigh.

Perhaps he’s regularly having That Conversation with himself. You know the one. I should be thankful, grateful, happy. Anything but this infuriating restlessness. Surely I have enough. What’s wrong with me?

It’s true that until recently, life seems to have treated him well. His early lane-change from architecture into graphic artistry has served his career well. He is happily married to his Swiss wife, whom he met while exploring Europe, and he has two young sons, with a third on the way. Financially, he’s not struggling. It seems like he’s living the dream.

But not everything is good. His son is in recovery, recently ravaged by tuberculosis. The shadow of international conflict is falling across Europe. He finds Belgium an absolutely miserable place to live.

And there’s his career. His artwork is seen as interesting, but it doesn’t quite fit. So severe! All those bold lines! He’s regarded as an oddball. Despite being a fan of Rennaisance Art and the work of the Impressionists, he feels increasingly pulled in a different direction…

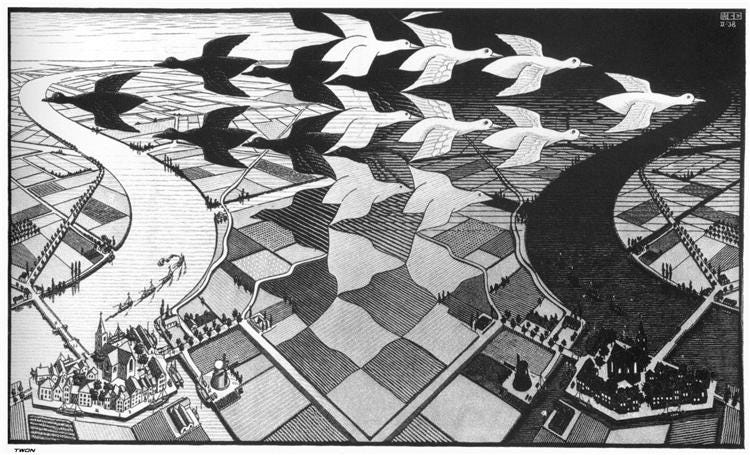

** Day And Night (1938): woodcut printed from two blocks, 39 x 68 cm. **

“Grey rectangular fields develop upwards into sillhouettes of white and black birds; the black ones are flying towards the left and the white ones towards the right, in two opposing formations. To the left of the picture the white birds flow together and merge to form a daylight sky and landscape. To the right the black birds melt together into night. The day and night landscapes are mirror images of each other, united by means of the grey fields out of which once again the birds emerge.”

- Escher’s notes from The Graphic Work Of MC Escher (1954).

When you look at this picture, you’re flipping between world views. Either you’re seeing the white birds, and the bright, presumably sunlit day scene with its cheerful flotilla of steam ships puffing their way upriver - or you’re seeing the black birds, and your eye is drawn to the night-shrouded landscape where the houses have their lights on and the sky’s already eaten the horizon & is creeping nearer…

Except, that’s not quite right. The black birds are in the daylight side, and the white ones are flying into the night. These aren’t just mirror images: they’re like the Ancient Chinese yin-yang symbol, each side containing part of its opposite.

(Yīnyáng - “dark/light” - is a representation of the concept of dualism, where apparently opposite or contrary forces are often complementary, interconnected, and interdependent in the natural world.)

Perhaps, as Europe plunges into the greatest paroxysm of violence in world history, Escher is quietly reminding everyone that ‘sides’ are never clear-cut things, and that boiling the world down into a series of false dilemmas is a great way to stop appreciating what’s actually in front of you.

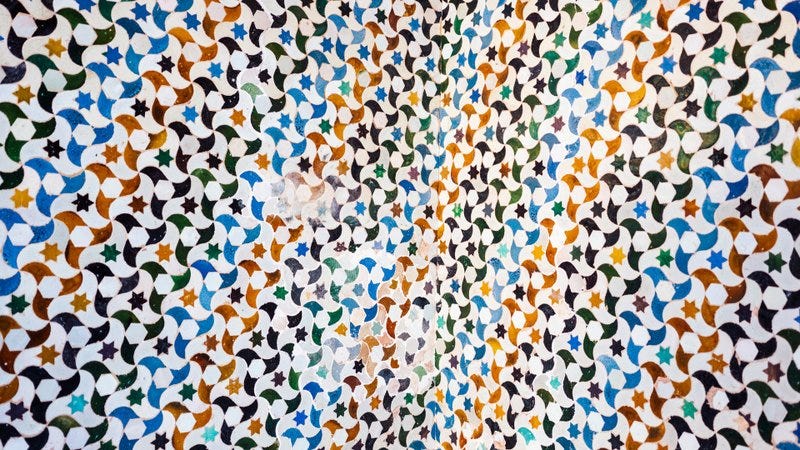

Or maybe he just likes the pattern. He’s been obsessed with tessellation (identical shapes that fit together) since he saw it showcased so spectacularly on the walls of Spain’s Alhambra palace:

The mathematical regularity so often seen in nature (for example, in a honeycomb) excites his brain - this weaving of the Real, even the intensely banal, into something surprising and thrilling.

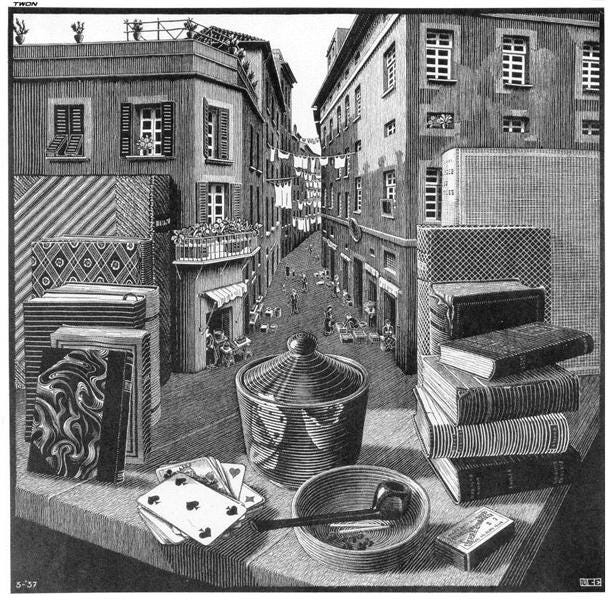

This isn’t to say he doesn’t bend reality in his work. Scroll back up to that window’s-eye-view up at the top (Still Life And View, 1937) and take a closer look. What did you miss?

But Escher’s love of the fantastical is primarily inspired by what he sees around him, not what he can dream up out of next to nothing.

In a lecture later in his life, he’ll explain this further:

“If you want to express something impossible, you must keep to certain rules. The element of mystery to which you want to draw attention should be surrounded and veiled by a quite obvious, readily recognisable commonness.”

By looking closely at the real world, and trying to understand how it works, Escher will invite his initially small but intensely loyal fanbase to explore some very strange mysteries indeed.

It’s 1954, and British mathematician Roger Penrose has just discovered Escher’s work at a conference in Amsterdam, finding himself "absolutely spellbound".

He isn’t the first. While Escher remains unpopular with the more traditional art scene (his work is considered insufficiently lyrical & far too intellectual for its own good), many scientists and mathematicians adore its playful geometries and obsessive precision in mapping the weird. Now here is a kindred spirit: an artist who sees with numbers.

Penrose is similarly enthused. He rapidly scribbles out some ideas for a homage to Escher, then turns to his father (the psychiatrist Lionel Penrose) for help. Together they throw together a paper for the British Journal of Psychology, depicting a joined staircase that can be sketched in two dimensions but is absolutely impossible in three.

After the article’s publication in 1958, the Penroses send a copy to Escher as thanks for the inspiration. Escher writes back:

“Your figures 3 and 4, the 'continuous flight of steps', were entirely new to me, and I was so taken by the idea that they recently inspired me to produce a new picture, which I would like to send to you as a token of my esteem. Should you have published other articles on impossible objects or related topics, or should you know of any such articles, I would be most grateful if you could send me further details.”

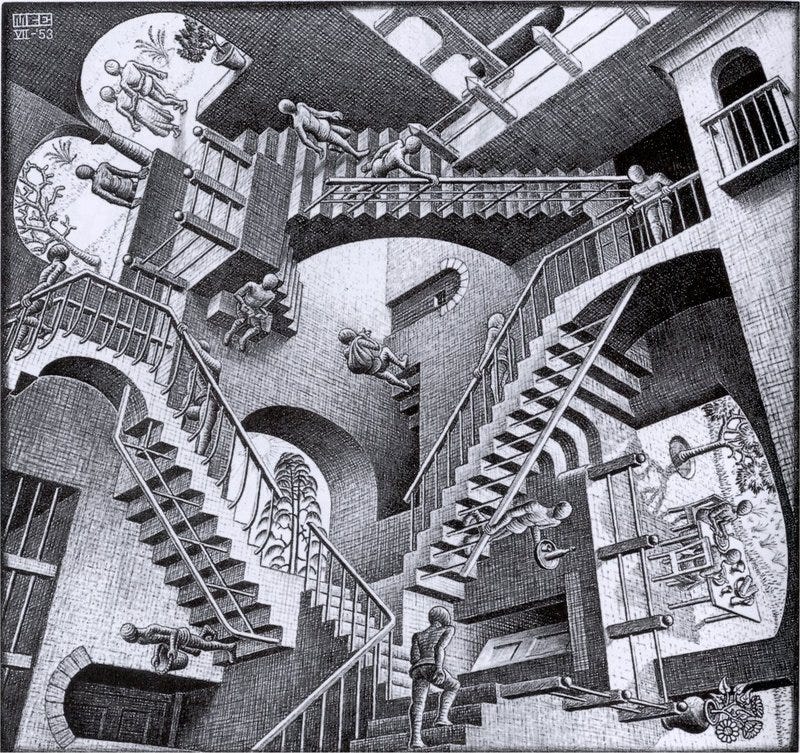

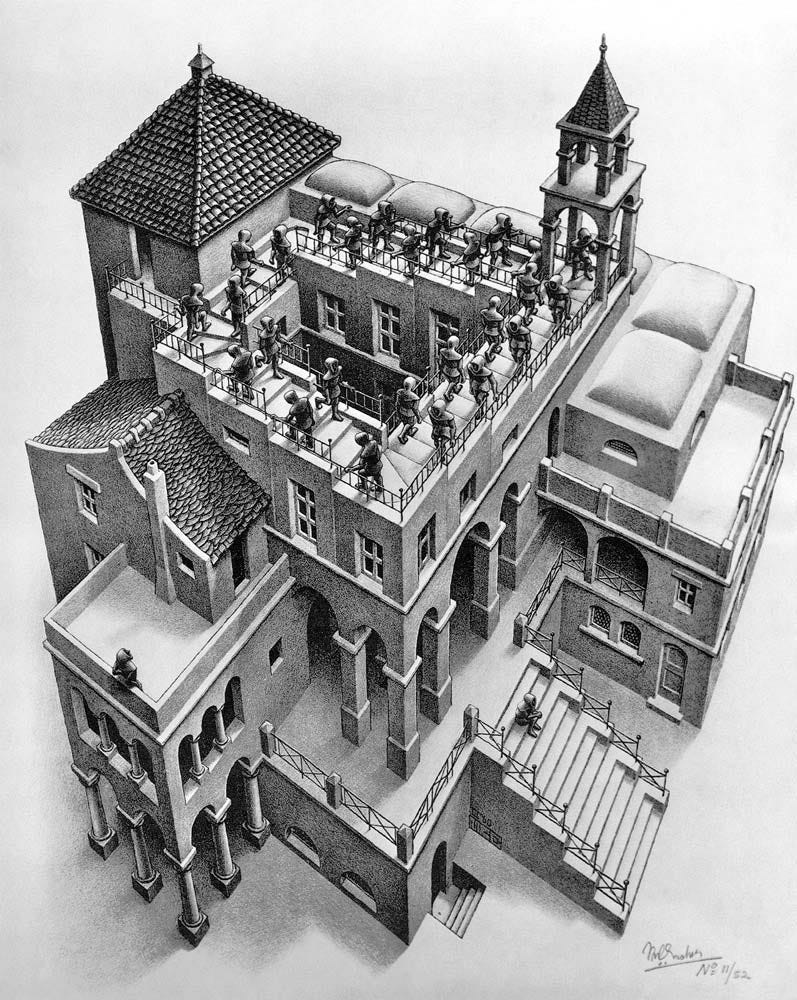

** Ascending And Descending (1960): lithograph, 38 x 26.5 cm. **

“A rectangular inner courtyard is bounded by a building that is roofed in by a never-ending stairway. The inhabitants of these living-quarters would appear to be monks, adherents of some unknown sect. Perhaps it is their ritual duty to climb those stairs for a few hours each day. It would seem that when they get tired they are allowed to turn about and go downstairs instead of up. Yet both directions, though not without meaning, are equally useless. Two recalcitrant individuals refuse, for the time being, to take any part in this exercise. They have no use for it at all, but no doubt sooner or later they will be brought to see the error of their nonconformity.”

- Escher’s notes from The Graphic Work Of MC Escher (1954).

It’s the 1960s now, and nonconformity is all the rage. Hair is getting longer, psychedelics-powered artistry is flourishing, and anything that seems to scream to hell with the rules is increasingly in vogue.

Escher is having none of it - but it’s still seeking him out anyway. Both Mick Jagger and Stanley Kubrick will unsuccessfully try to charm him into something collaborative (his delightfully cranky response to one letter: “Please tell Mr Jagger I am not Maurits to him”).

Because of the fantastical elements of his work, Escher is acquiring a reputation as a surrealist. As a self-identifying “reality enthusiast,” it’s the very last thing he wants. Take Ascending & Descending, where he’s clearly turning his imagination to the futility of so much in the human-centred world. In a letter to a friend, he says:

“Yes, yes, we climb up and up, we imagine we are ascending; one step is about 10 inches high, terribly tiring - and where does it get us? Nowhere.”

But until the end of his career, his work will continue to speak to something deeper - a rebellion against human incuriosity, or a constant rallying-cry for the act of paying attention.

His very last piece, Snakes (1969), draws your eye towards infinity, as if to say This is as far as I can see, what about you?

After a lifetime of studying and playing with the geometries of landscapes, human architecture, plants and insects with an intuitive grasp of the mathematical relationships underpinning them, Escher will leave his work to speak for him, accompanied by a handful of accompanying notes and letters. To the last, he remains a man at his desk, doing things by hand (including making prints of his work: Day and Night eventually proved so popular that he had to reproduce it himself 600 times). The art is his whole message.

For this reason, it’s dangerous to read too far into his work, to attempt to translate it into anything it essentially wasn’t.

But it’s fun to speculate, so let’s do that.

Look again at Ascending & Descending, my favourite of all his works. Yes, the staircase is grim to contemplate, and an easy thing to cynically stick a new label upon (like “traditional employment,” or “social media,” or even “Metaverse”). Depressing, right? Especially the ‘you can have a rest by going downhill!’ side of things, which seems particuarly bleak.

But I love it because of everything else in the picture. It’s not just an infinite staircase - it’s a building.

Where do all those doorways lead? Especially that one at ground level, with steps leading underground? Look at that doorway on the far left of the staircase - presumably it connects with the rest of the house. The monks aren’t trapped. They’re just so fixated on the staircase that they don’t see everything else the building offers.

This is also true of the “recalcitrant individuals” - one staring at the ground in apparent misery, the other looking up at his fruitlessly toiling peers as if thinking oh well, I guess if everyone else is doing it…?” They also appear to see none of it.

Perhaps this is a stretch. Perhaps it’s just down to Escher’s lifelong love of architecture, combined with the need for a “quite obvious, readily recognisable commonness” to frame his endless, universe-breaking staircase. But maybe it’s also his curiosity, optimism and love of the as-yet-unknown, finding a way to creep into even his most downbeat piece of work?

Certainly doesn’t seem impossible.

For more examples of Escher’s work, check out Nishant Jain’s thoughtful post here at SneakyArtist.com.

Images: WikiArt.org; Kadir Celep.

I never thought about the doorways! Thanks for this -- what a fun one. I loved learning that Escher inspired mathematicians (as a maths-inclined person myself who loves advocating for its role in helping us translate patterns and relationships in nature ...)

Thanks for the shoutout, Mike! 🙏 I enjoyed reading this.